When Movies Leveled Up

Special effects have never been just about flash. At their core, they’re about solving impossible problems, dreaming up ways to show audiences something that technology hasn’t quite caught up with yet. Every so often, a film arrives that doesn’t just wow viewers; it changes the rules for everyone. These are the movies that didn’t just raise the bar, they reinvented it, piecing together breakthroughs with miniatures, clever engineering, raw mathematics, and early computers that were still learning how to crawl.

Screenshot from Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Touchstone Pictures (1988)

Screenshot from Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Touchstone Pictures (1988)

A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Before this film, movies mostly recorded real life. Georges Méliès decided they could lie instead, beautifully. Using stop tricks, painted sets, and camera manipulation, he turned cinema into illusion. The iconic moon image wasn’t just memorable, it announced that movies could create worlds, not just observe them.

Screenshot from A Trip to the Moon, Star Film Company (1902)

Screenshot from A Trip to the Moon, Star Film Company (1902)

Metropolis (1927)

Metropolis made audiences believe a futuristic city could exist decades before skyscrapers dominated skylines. Miniatures, clever in-camera effects, and massive set pieces created a sense of scale that felt overwhelming. Its imagery stuck around long after silent cinema faded, quietly shaping how science fiction would imagine the future for generations.

Screenshot from Metropolis, Universum Film AG (UFA) (1927)

Screenshot from Metropolis, Universum Film AG (UFA) (1927)

King Kong (1931)

Kong worked because he wasn’t just big, he felt alive. Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion animation gave the creature personality, fear, and even tenderness. By combining miniatures, rear projection, and live actors, the film created emotional investment in a visual effect, something that hadn’t really happened before.

Screenshot from King Kong, RKO Radio Pictures (1933)

Screenshot from King Kong, RKO Radio Pictures (1933)

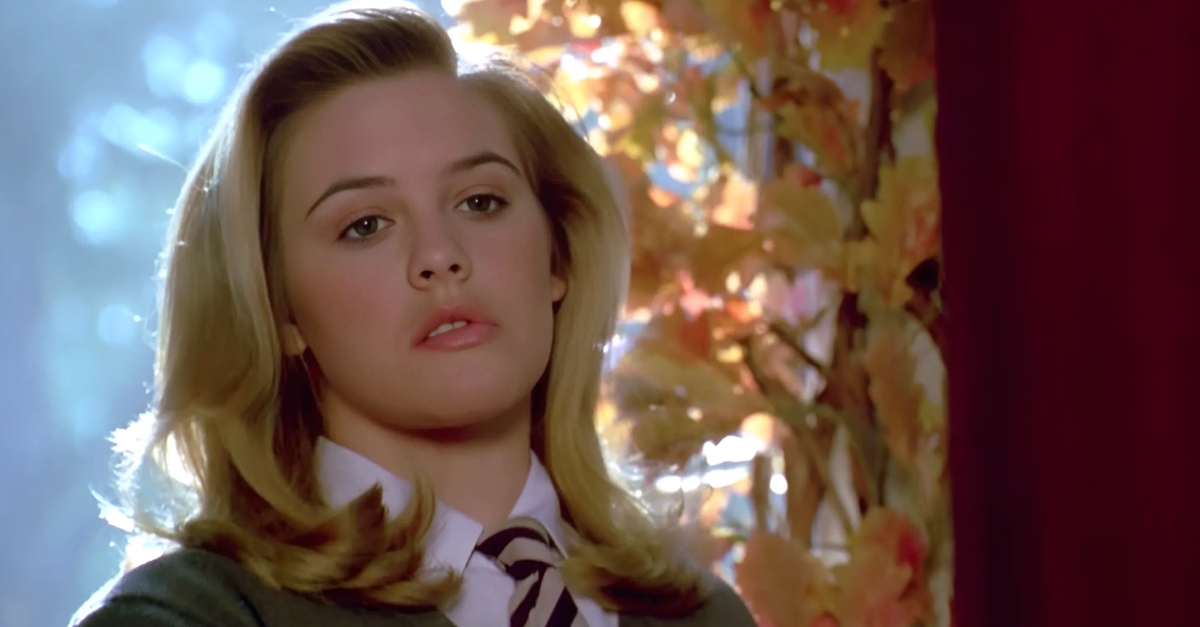

Things To Come (1936)

This film looked forward when most cinema was still grounded in the present. Its futuristic cities, technology, and warfare felt bold and unsettling, built through ambitious miniature work. It treated science fiction as a space for serious ideas rather than escapism, helping push the genre toward something more thoughtful and visually ambitious.

Screenshot from Things to Come, United Artists (1936)

Screenshot from Things to Come, United Artists (1936)

The Wizard Of Oz (1939)

Every inch of this movie feels designed. Matte paintings, practical creatures, early color effects, and elaborate sets came together to create a fantasy world that still feels tangible. The shift from Kansas to Oz remains one of cinema’s most effective visual moments, not because of complexity, but because of emotional timing.

Screenshot from The Wizard of Oz, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

Screenshot from The Wizard of Oz, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

Citizen Kane (1941)

The effects in Citizen Kane rarely call attention to themselves, which is exactly why they mattered. Miniatures expanded spaces, optical tricks extended sets, and deep focus photography changed how scenes were staged. The visuals quietly reshaped cinematic language, influencing how filmmakers thought about space and perspective rather than spectacle.

Screenshot from Citizen Kane, RKO Radio Pictures (1941)

Screenshot from Citizen Kane, RKO Radio Pictures (1941)

Gojira (1954)

Instead of animating a monster, Japan put a performer inside one. Suitmation gave Gojira weight, movement, and presence that felt physical and destructive. Combined with meticulously built miniatures, the devastation felt real. That tactile approach defined kaiju cinema and offered a different path from Hollywood monster effects.

Screenshot from Gojira, Toho Co., Ltd. (1954)

Screenshot from Gojira, Toho Co., Ltd. (1954)

The Ten Commandments (1956)

The Red Sea sequence still feels impossible when you know how it was made. Massive water tanks filmed in reverse, carefully composited together, created an illusion that stunned audiences. The effect leaned on ingenuity rather than technology, proving scale could be achieved through clever planning instead of expensive shortcuts.

Screenshot from The Ten Commandments, Paramount Pictures (1956)

Screenshot from The Ten Commandments, Paramount Pictures (1956)

Jason And The Argonauts (1963)

Ray Harryhausen’s skeleton battle didn’t just impress, it mesmerized. Frame-by-frame animation allowed creatures to fight live actors convincingly, something no one had pulled off this cleanly before. The sequence became a rite of passage for future filmmakers, many of whom cite it as the moment they fell in love with effects.

Screenshot from Jason and the Argonauts, Columbia Pictures (1963)

Screenshot from Jason and the Argonauts, Columbia Pictures (1963)

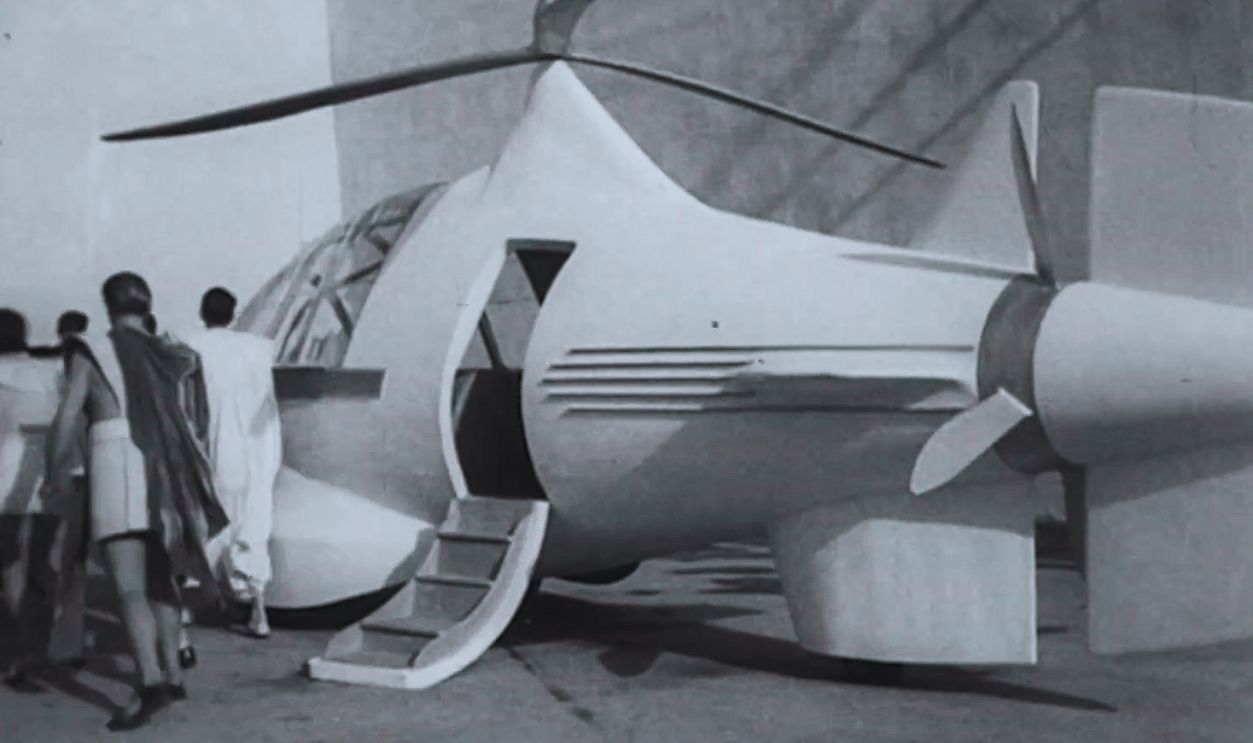

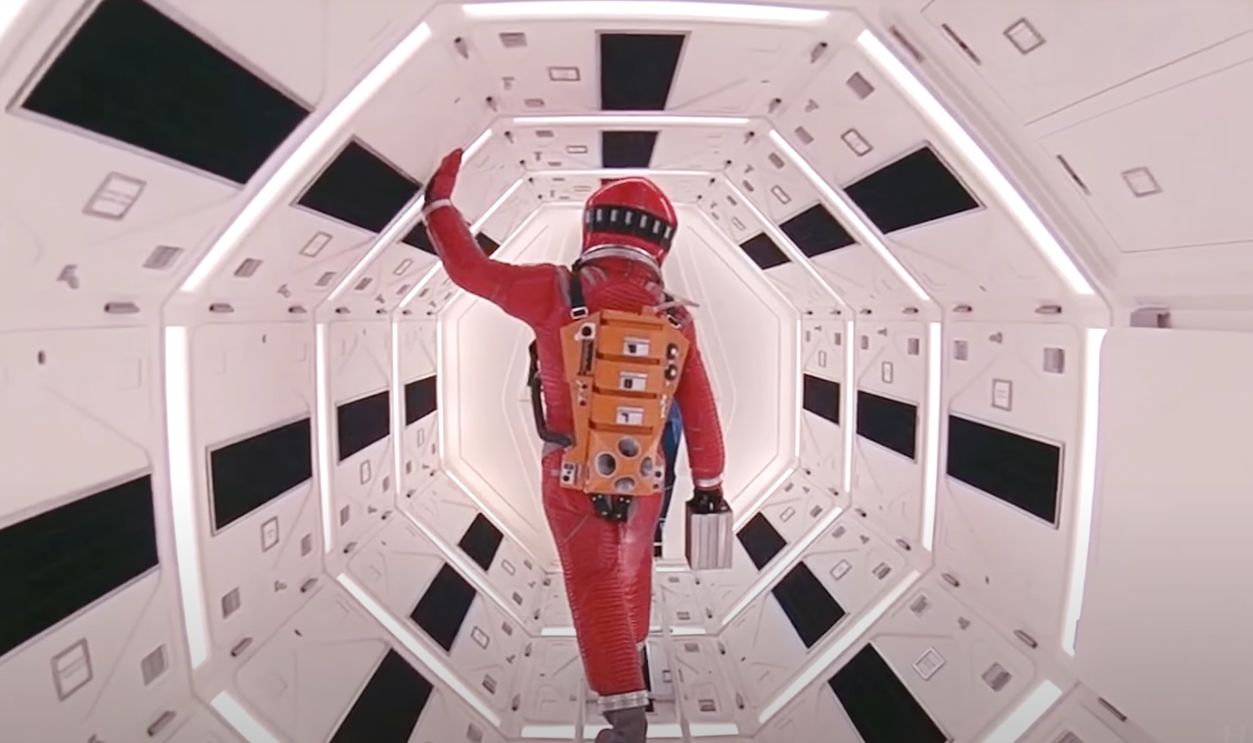

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanley Kubrick chased realism with obsessive patience. Rotating sets simulated weightlessness, miniatures were filmed with extreme precision, and front projection created seamless environments. The result still feels grounded decades later. Space finally looked quiet, vast, and believable, shifting science fiction away from fantasy toward something more contemplative.

Screenshot from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) (1968)

Screenshot from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) (1968)

Jaws (1975)

The shark barely worked, and that changed everything. Forced to hide it, Spielberg leaned into pacing, editing, and sound. The tension became unbearable long before the creature appeared. When it finally did, audiences were already hooked. Limitation ended up creating one of the most effective uses of effects in cinema history.

Screenshot from Jaws, Universal Pictures (1975)

Screenshot from Jaws, Universal Pictures (1975)

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977)

To make Star Wars, George Lucas had to reinvent visual effects infrastructure from scratch. Motion-control cameras allowed dynamic space battles, while detailed miniatures gave the galaxy texture and grit. The film didn’t just look different, it felt alive, kicking off the modern blockbuster era almost overnight.

Screenshot from Star Wars: A New Hope, 20th Century Fox (1977)

Screenshot from Star Wars: A New Hope, 20th Century Fox (1977)

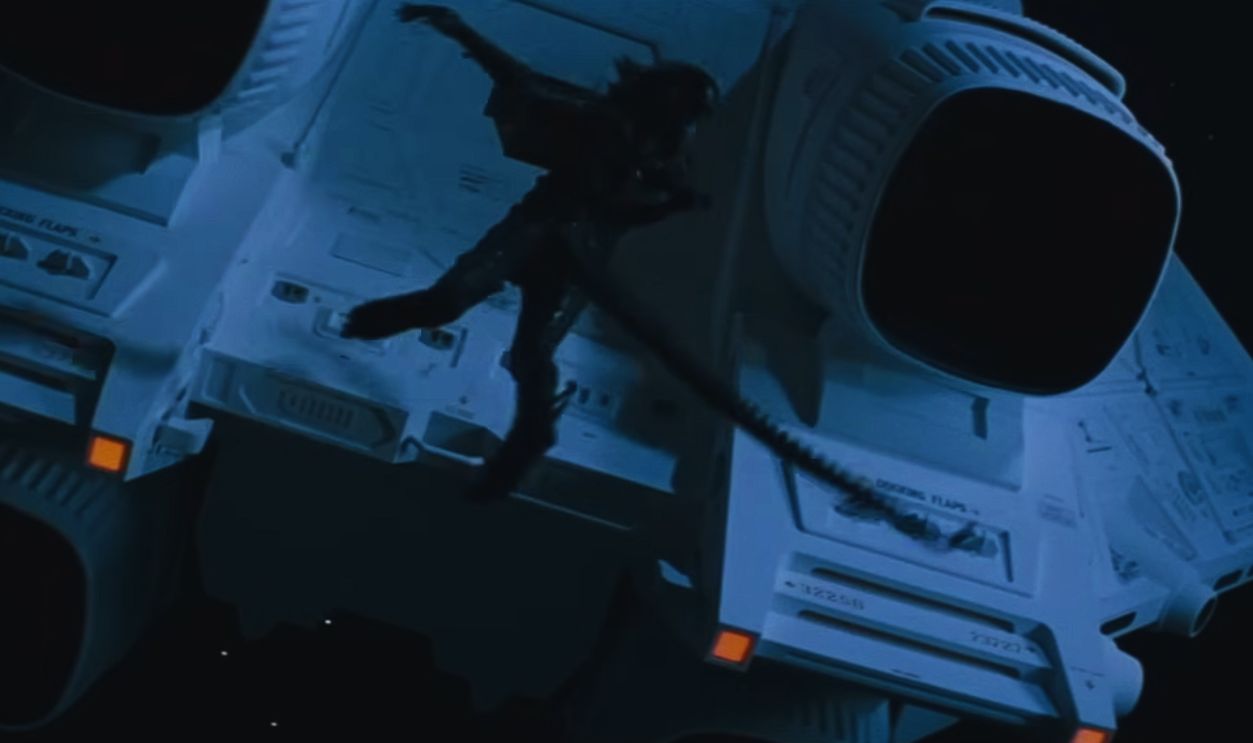

Alien (1979)

Nothing about Alien feels clean or safe. The creature design is unsettling, the sets feel industrial and cramped, and the effects emphasize texture over spectacle. Miniatures, practical creatures, and lighting work together to create dread. The horror comes from what feels real and uncomfortable, not what feels flashy.

Screenshot from Alien, 20th Century Fox (1979)

Screenshot from Alien, 20th Century Fox (1979)

An American Werewolf In London (1981)

This transformation scene shocked audiences because it took its time. Bones stretch, skin moves, and pain is visible. Using mechanical rigs and prosthetics, the sequence feels brutal rather than magical. It raised expectations for creature effects and turned makeup work into something audiences actively watched for.

Screenshot from An American Werewolf in London, Universal Pictures (1981)

Screenshot from An American Werewolf in London, Universal Pictures (1981)

The Thing (1982)

Rob Bottin went all in. Puppets, prosthetics, animatronics, and goo combined to create transformations that felt unpredictable and wrong. Nothing looked polished or safe. The effects feel alive in the worst way, which is why they still disturb viewers decades later, even in an era dominated by CGI.

Screenshot from The Thing, Universal Pictures (1982)

Screenshot from The Thing, Universal Pictures (1982)

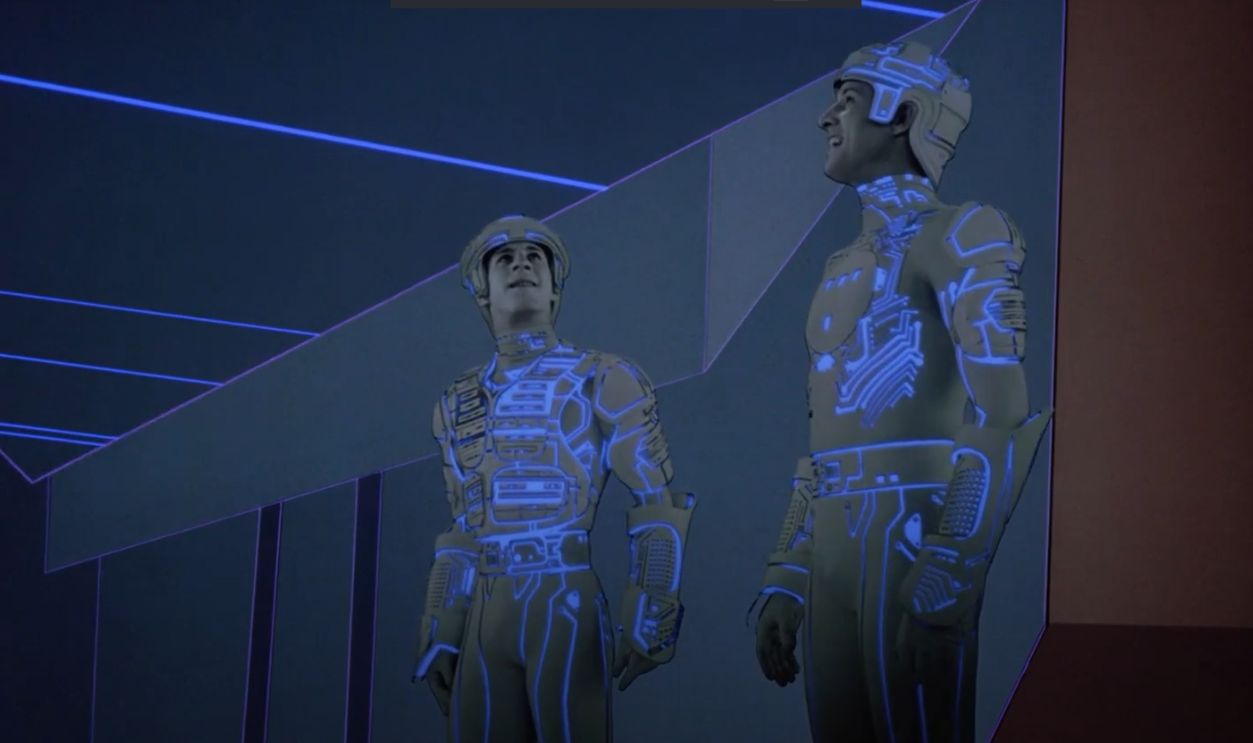

Tron (1982)

Tron looked like it came from another dimension. Early CGI environments, combined with backlit animation and bold design choices, created a digital world unlike anything before it. The technology was limited, but the ambition was massive. It cracked open the door for computers to become part of cinematic storytelling.

Screenshot from Tron, Walt Disney Productions (1982)

Screenshot from Tron, Walt Disney Productions (1982)

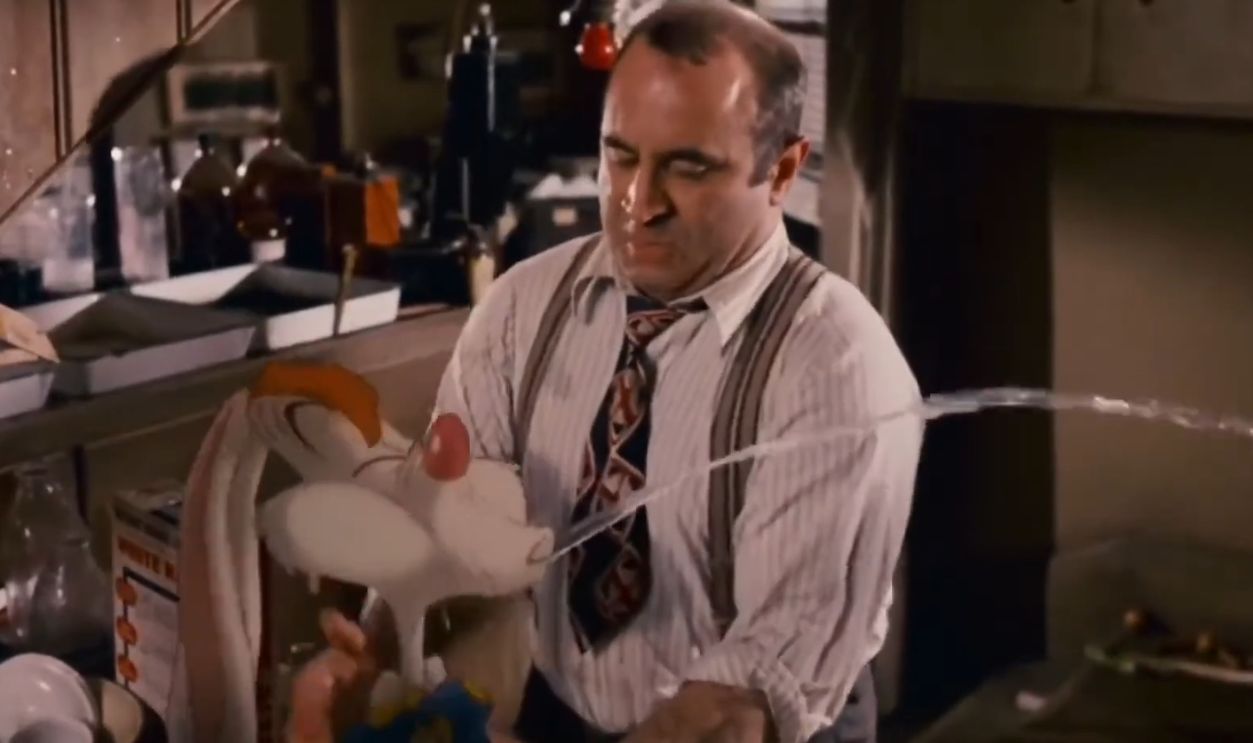

Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)

Making cartoons feel real alongside human actors required obsessive precision. Shadows, eye lines, props, and lighting had to match perfectly. The result made animated characters feel physically present in the world. Even now, the craftsmanship holds up, setting a benchmark for blending animation and live action.

Screenshot from Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Touchstone Pictures (1988)

Screenshot from Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Touchstone Pictures (1988)

Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991)

The T-1000 felt revolutionary because it moved like nothing else. Liquid metal flowed, reformed, and reacted to the environment in ways practical effects couldn’t manage. Paired with real stunts and explosions, the digital work didn’t feel separate. It felt like part of the physical world.

Screenshot from Terminator 2: Judgment Day, TriStar Pictures (1991)

Screenshot from Terminator 2: Judgment Day, TriStar Pictures (1991)

Dead Alive (Braindead) (1992)

This film embraced excess with enthusiasm. Homemade rigs, over-the-top prosthetics, and absurd quantities of fake blood turned practical effects into a spectacle of invention. While intentionally outrageous, the craftsmanship behind the chaos showed just how far physical effects could be pushed with creativity and commitment.

Screenshot from Dead Alive (Braindead), Trimark Pictures (1992)

Screenshot from Dead Alive (Braindead), Trimark Pictures (1992)

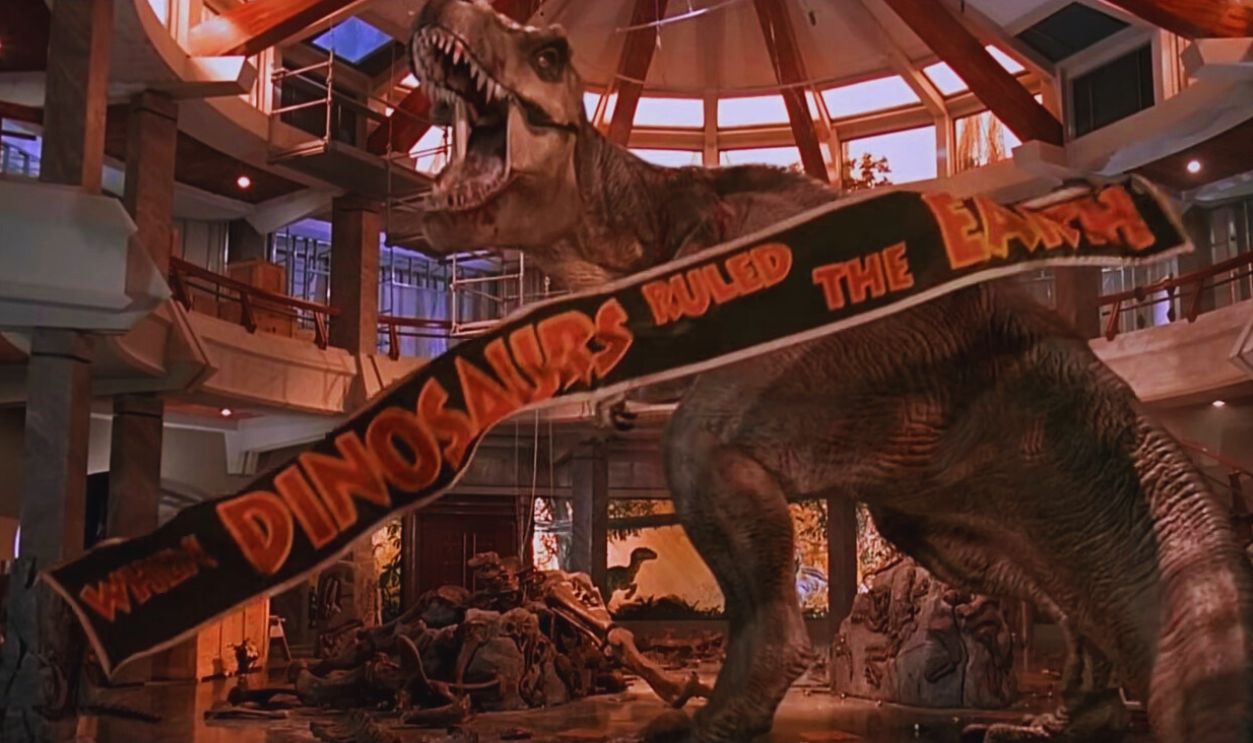

Jurassic Park (1993)

Dinosaurs finally felt alive. Animatronics handled close-ups, while CGI filled in movement and scale. The careful balance kept everything grounded. Instead of overwhelming audiences with effects, the film used restraint, making every appearance count. That balance changed how filmmakers approached digital creatures moving forward.

Screenshot from Jurassic Park, Universal Pictures (1993)

Screenshot from Jurassic Park, Universal Pictures (1993)

The Matrix (1999)

Bullet time instantly rewired action cinema. Freezing motion while the camera moved created a surreal sense of control over time itself. Achieved through camera arrays and digital stitching, the effect became iconic overnight. Suddenly, action scenes weren’t just fast, they were sculpted and choreographed like visual puzzles.

Screenshot from The Matrix, Warner Bros. Pictures (1999)

Screenshot from The Matrix, Warner Bros. Pictures (1999)

The Lord Of The Rings Trilogy (2001–2003)

Weta Digital built new tools to handle massive armies, digital landscapes, and performance capture. Gollum’s expressive face alone shifted expectations for digital characters. Across three films, effects served emotion and scale without swallowing the story, proving epic fantasy could feel intimate and believable.

Screenshot from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, New Line Cinema (2002)

Screenshot from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, New Line Cinema (2002)

The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button (2008)

This film quietly advanced digital aging. Brad Pitt’s face was mapped onto CGI bodies with subtlety that avoided distraction. The technology disappeared into the performance, letting the story breathe. It marked a shift toward effects that support emotion rather than demand attention.

Screenshot from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Paramount Pictures (2008)

Screenshot from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Paramount Pictures (2008)

Avatar (2009)

James Cameron treated performance capture as its own language. Actors performed in digital environments that responded in real time, allowing emotion to drive animation. Combined with immersive 3D, the film changed how studios thought about world-building, production pipelines, and audience immersion on a massive scale.

Screenshot from Avatar, 20th Century Fox (2009)

Screenshot from Avatar, 20th Century Fox (2009)

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

At a time when CGI dominated, Fury Road leaned hard into real stunts and practical explosions. Digital tools were used sparingly, mostly to enhance what was already there. The result feels visceral and immediate. It reminded audiences that nothing beats physical danger when it comes to spectacle.

Screenshot from Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros. Pictures (2015)

Screenshot from Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros. Pictures (2015)

You May Also Like:

TV Shows That Were So Iconic They Changed The World Forever

Forget The Critics: These Are The 50 Greatest Albums Of All Time—Do You Agree?

Alt-Rock Albums That Rewrote All The Rules And Changed Music Forever