The movies that lived on cable—and quietly disappeared

For years, these films were treated as common knowledge. They played on TV, sat on shelves, and came up in conversation without explanation. Boomers didn’t recommend them—they assumed you'd seen them. Millennials, meanwhile, grew up just far enough removed that the assumption could no longer be assumed. And the result is a long list of “classic” war movies that quietly (and sadly) skipped an entire generation.

“The Longest Day” (1962)

Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck and loaded with stars like John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and Robert Mitchum, this D-Day epic prioritizes scope and historical detail over emotional focus. It was long treated as required viewing, less a movie night pick than a cinematic history lesson.

Screenshot from The Longest Day, United Artists (1962)

Screenshot from The Longest Day, United Artists (1962)

“The Dirty Dozen” (1967)

Directed by Robert Aldrich and starring Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, and Jim Brown, this film popularized the idea of a ragtag group sent on a high-risk mission. That setup has been recycled endlessly in action and war movies since. Most viewers know the formula well—far fewer know where it actually started. But Boomers sure do!

Screenshot from The Dirty Dozen, MGM (1967)

Screenshot from The Dirty Dozen, MGM (1967)

“Patton” (1970)

Directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, George C. Scott’s Oscar-winning performance turned General Patton into a cultural force. The speeches, the ego, the contradictions—all of it became shorthand for command and bravado. Plenty of people recognize the cadence and quotes today, even if they couldn’t tell you which movie they’re echoing.

Screenshot from Patton, 20th Century Fox (1970)

Screenshot from Patton, 20th Century Fox (1970)

“Twelve O’Clock High” (1949)

Directed by Henry King and starring Gregory Peck, this film is famous for treating leadership as psychological erosion rather than heroism. It was studied, cited, and even used in military training contexts. Its reputation rests on seriousness and restraint—qualities that once signaled importance without needing promotion.

Screenshot from Twelve O’Clock High, 20th Century Fox (1949)

Screenshot from Twelve O’Clock High, 20th Century Fox (1949)

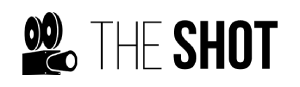

“The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957)

Directed by David Lean and starring Alec Guinness, this Best Picture winner explores pride and obsession disguised as discipline. Its whistled march and moral tension once made it unavoidable in discussions of classic cinema. Today, it’s respected more than revisited.

Screenshot from The Bridge on the River Kwai, Columbia Pictures (1957)

Screenshot from The Bridge on the River Kwai, Columbia Pictures (1957)

“Run Silent, Run Deep” (1958)

Directed by Robert Wise and starring Clark Gable and Burt Lancaster, this submarine thriller is built on silence, procedure, and command conflict. It belongs to a mid-century naval-film tradition that valued tension over spectacle—and trusted audiences to lean in.

Screenshot from Run Silent, Run Deep, United Artists (1958)

Screenshot from Run Silent, Run Deep, United Artists (1958)

“The Guns of Navarone” (1961)

Directed by J. Lee Thompson and starring Gregory Peck and David Niven, this mission-driven WWII epic became a blueprint. Clear objectives, mounting obstacles, and professionals doing their jobs. It was once a default recommendation for “a good war movie.”

Screenshot from The Guns Of Navarone, Columbia Pictures Corporation (1961)

Screenshot from The Guns Of Navarone, Columbia Pictures Corporation (1961)

“A Bridge Too Far” (1977)

Directed by Richard Attenborough, this meticulous account of Operation Market Garden features Sean Connery, Gene Hackman, and Anthony Hopkins in restrained roles. Its reputation comes from accuracy and humility—the rare war film remembered for showing how confidence quietly turns into failure.

Screenshot from A Bridge Too Far, United Artists (1977)

Screenshot from A Bridge Too Far, United Artists (1977)

“Stalag 17” (1953)

Directed by Billy Wilder and starring William Holden, this Oscar-winning POW film mixes suspicion, cynicism, and dry humor. It refuses easy heroics, focusing instead on trust and betrayal. Its reputation grew from how sharp—and unsentimental—it was for its era.

Screenshot from Stalag 17, Paramount Pictures (1953)

Screenshot from Stalag 17, Paramount Pictures (1953)

“Midway” (1976)

Directed by Jack Smight, this film leaned heavily on real combat footage and historical detail. It’s dense, crowded, and unapologetically technical. For decades, that density was taken as proof of seriousness rather than a flaw.

“The Great Escape” (1963)

Directed by John Sturges and starring Steve McQueen, James Garner, and Richard Attenborough, this film became essential viewing for decades. The camaraderie and slow-burn tension mattered more than the famous motorcycle jump. And all those movies since that have had a character bouncing a ball against the wall...how many millennials got the reference?

Screenshot from The Great Escape, United Artists (1963)

Screenshot from The Great Escape, United Artists (1963)

“From Here to Eternity” (1953)

Directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift, and Deborah Kerr, this Oscar juggernaut explores military hierarchy and quiet rebellion before Pearl Harbor. It’s often reduced to a single beach scene, which undersells how much ground the film actually covers.

Columbia Pictures, Wikimedia Commons

Columbia Pictures, Wikimedia Commons

“Battleground” (1949)

Directed by William A. Wellman, a former combat pilot, this film focuses on fatigue, waiting, and survival during the Battle of the Bulge. It avoids speeches and spectacle entirely. Its authority comes from how little it tries to impress.

William A. Wellman, Wikimedia Commons

William A. Wellman, Wikimedia Commons

“The Enemy Below” (1957)

Directed by Dick Powell and starring Robert Mitchum and Curt Jürgens, this submarine duel is built around mutual respect between adversaries. The film treats skill and professionalism as universal traits—an approach that quietly influenced decades of storytelling. To younger generations the name means nothing—besides the fact that it would be a good title for a reality show.

Screenshot from The Enemy Below, 20th Century Studios (1957)

Screenshot from The Enemy Below, 20th Century Studios (1957)

“Go Tell the Spartans” (1978)

Directed by Ted Post and starring Burt Lancaster, this Vietnam-era film is bleak and stripped down. It avoids dramatic arcs and easy meaning, opting instead for inevitability. Its reputation grew slowly, mostly through word-of-mouth rather than rediscovery.

Screenshot from Go Tell the Spartans, United Artists (1978)

Screenshot from Go Tell the Spartans, United Artists (1978)

“Kelly’s Heroes” (1970)

Directed by Brian G. Hutton and starring Clint Eastwood, Donald Sutherland, and Telly Savalas, this WWII oddity blends combat, counterculture humor, and a heist structure. It played constantly on cable for years. To a lot of younger viewers now, it sounds less like a movie and more like a forgotten video game title.

Screenshot from Kelly’s Heroes, MGM (1970)

Screenshot from Kelly’s Heroes, MGM (1970)

“In Harm’s Way” (1965)

Directed by Otto Preminger and starring John Wayne and Kirk Douglas, this long, serious film emphasizes consequence over bravado. It’s more reflective than its cast suggests, and more interested in moral cost than battlefield heroics.

Screenshot from In Harm’s Way, Paramount Pictures (1965)

Screenshot from In Harm’s Way, Paramount Pictures (1965)

“The Big Red One” (1980)

Written and directed by Sam Fuller, a WWII veteran, this semi-autobiographical film stars Lee Marvin and a young Mark Hamill. Its episodic structure feels more like memory than narrative, which is exactly what gives it weight.

Screenshot from The Big Red One, United Artists (1980)

Screenshot from The Big Red One, United Artists (1980)

“The Desert Fox” (1951)

Directed by Henry Hathaway and starring James Mason as Erwin Rommel, this film treats enemy leadership with unusual nuance. That complexity made it notable in its time—and controversial enough to be remembered. But not by most Millennials unfortunately.

Screenshot from The Desert Fox, 20th Century Fox (1951)

Screenshot from The Desert Fox, 20th Century Fox (1951)

“Hell Is for Heroes” (1962)

Directed by Don Siegel and starring Steve McQueen, this small-scale WWII film focuses on pressure and fear rather than spectacle. It’s tightly wound, serious, and unconcerned with leaving behind iconic moments.

Screenshot from Hell Is for Heroes, Paramount Pictures (1962)

Screenshot from Hell Is for Heroes, Paramount Pictures (1962)

“The Hill” (1965)

Directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Sean Connery, this military prison drama is brutal and claustrophobic. Authority, punishment, and obedience grind everyone down. It’s war stripped of heroics—and that refusal to soften it defined its reputation.

Screenshot from The Hill, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1965)

Screenshot from The Hill, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1965)

You Might Also Like:

Directors Who Never Miss—And The One Time They Did

Movie Taglines That Were Almost Too Good For The Actual Films