When The Studio System Finally Freaked Out

By the 1960s, old-school Hollywood was running on fumes. The star system was wobbling, TV was stealing eyeballs, censorship rules were cracking and a wave of international filmmakers were basically sending Hollywood a memo that said: “Catch up or get left behind”.

Out of that chaos came what we now call modern Hollywood—the era of director-driven blockbusters, gritty antiheroes, experimental editing, genre mash-ups and audiences who expected more than comforting happy endings. These 21 films don’t just define the 1960s; they helped build the cinematic world we still live in today.

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964)

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb proved you could make a studio-backed comedy about nuclear apocalypse and still pack theaters. Its dry, absurd tone and political bite showed that audiences were ready for satire that didn’t talk down to them. Modern Hollywood’s mix of prestige politics and popcorn spectacle owes a lot to this room of weirdos.

La Dolce Vita (1960)

With La Dolce Vita, Fellini turned a gossip columnist’s nightlife into an operatic mood piece about emptiness and celebrity. The film’s episodic structure and paparazzi imagery basically invented the modern idea of fame as a hollow circus. You can feel its influence in everything from awards-season “serious dramas” to the way Hollywood films stalk their own stars.

Screenshot from La Dolce Vita, Cineriz

Screenshot from La Dolce Vita, Cineriz

Breathless (1960)

Breathless detonated the rulebook on how a movie could be shot and cut. Godard’s jump cuts, street production and casual cool made filmmaking feel like something alive. Hollywood’s young directors watched it and realized they didn’t need permission anymore, which is pretty much the origin story of New Hollywood.

Screenshot from Breathless, Societe Nouvelle de Cinematographie

Screenshot from Breathless, Societe Nouvelle de Cinematographie

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

2001: A Space Odyssey took sci-fi out of the B-movie bargain bin and shot it into the realm of serious art. Kubrick’s slow, hypnotic pacing and abstract ending forced studios to reckon with the idea that audiences might accept ambiguity—and even like it. Every effects-driven epic that tries to be “mind-blowing” as well as marketable is following in its orbit.

Screenshot from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Screenshot from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Yojimbo (1961)

Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo is a samurai film that secretly laid the blueprint for the modern Hollywood antihero. Its nameless, smirking swordsman manipulates rival gangs for his own ends, and the movie plays like a dry run for countless Westerns and crime films. When it was unofficially remade as A Fistful of Dollars, the loop between Japanese cinema and Hollywood was sealed.

Screenshot from Yojimbo, Toho Co., Ltd.

Screenshot from Yojimbo, Toho Co., Ltd.

Psycho (1960)

Psycho took out its apparent star halfway through the story, turned a roadside motel into a nightmare and casually rewired audience expectations. Hitchcock’s marketing—no late admittance, no spoilers—felt like a prototype for modern event-movie hype. It also nudged Hollywood toward more explicit danger and psychological horror, paving the way for the slasher boom decades later.

Screenshot from Psycho, Paramount Pictures

Screenshot from Psycho, Paramount Pictures

In The Heat Of The Night (1967)

In the Heat of the Night showed that a charged crime drama could be both a Best Picture winner and a commercial hit. Sidney Poitier’s “They call me Mister Tibbs" slapback against Southern prejudice felt shockingly confrontational coming from a major studio release. The film helped make socially conscious thrillers a viable Hollywood staple instead of a niche risk.

Screenshot from In The Heat Of The Night, United Artists

Screenshot from In The Heat Of The Night, United Artists

West Side Story (1961)

West Side Story fused Broadway musical flair with kinetic, location-based filmmaking and vivid stylization. Its mixture of romance, tension and urban grit pushed the musical closer to the dramatic realism Hollywood would increasingly chase. Even with its serious representation problems, it proved that song-and-dance could coexist with gang issues and tragedy on a massive budget.

Screenshot from West Side Story, United Artists

Screenshot from West Side Story, United Artists

Planet Of The Apes (1968)

Planet of the Apes is essentially a blockbuster with a film-school thesis attached. The masks and monkey suits made it toy-friendly, but the downbeat twist and social commentary about war, science and human arrogance gave it staying power. It’s an early example of the franchise model—sequels, reboots, expanded lore—that modern Hollywood now runs on.

Screenshot from Planet Of The Apes, 20th Century Fox

Screenshot from Planet Of The Apes, 20th Century Fox

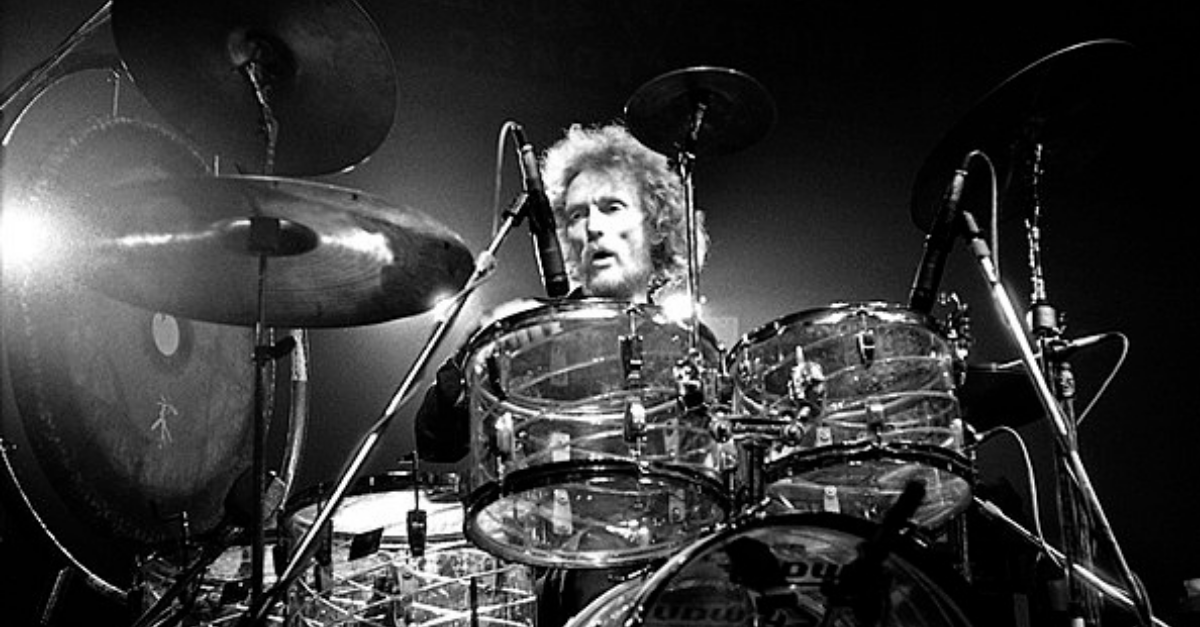

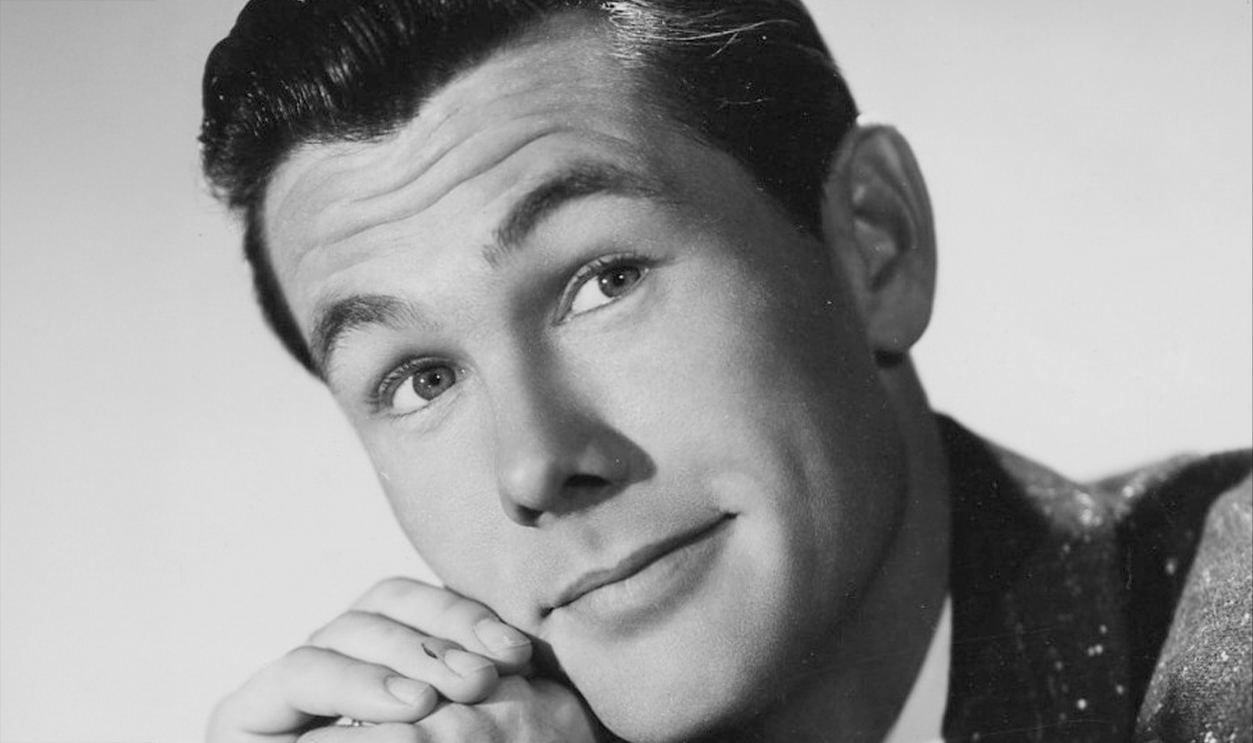

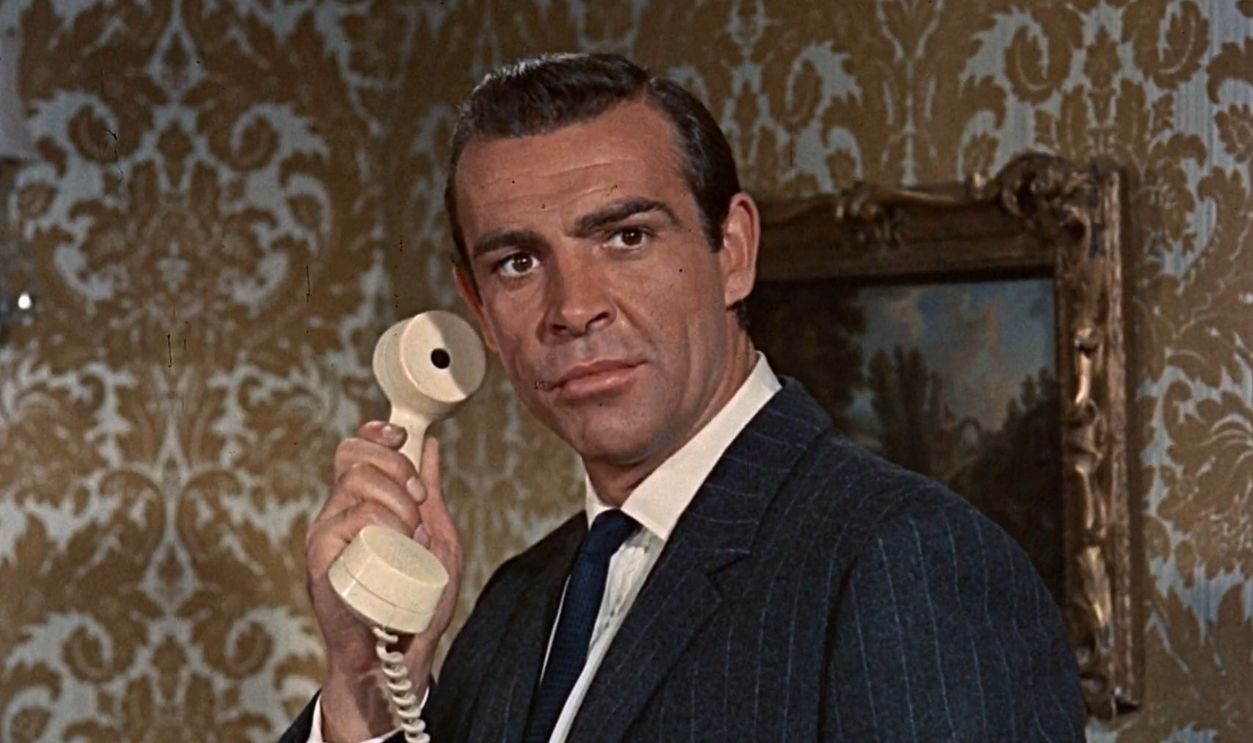

From Russia With Love (1963)

From Russia with Love cemented the James Bond recipe: exotic locations, gadgets, suave espionage and serialized villains. It proved that audiences would come back for the same hero again and again as long as the packaging felt fresh. Hollywood’s obsession with “cinematic universes” and recurring IP icons can trace a line right back to 1960s Bond mania.

Screenshot from From Russia With Love, United Artists

Screenshot from From Russia With Love, United Artists

The Birds (1963)

With The Birds, Hitchcock turned a quiet seaside town into an apocalyptic playground without explaining why anything was happening. That refusal to offer neat answers, paired with precise suspense set pieces, feels incredibly modern. Contemporary disaster, monster and “prestige horror” movies still copy the film’s escalating set-piece structure and eerie lack of closure.

Screenshot from The Birds, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from The Birds, Universal Pictures

The Apartment (1960)

The Apartment brought workplace politics, adultery and loneliness into a bittersweet studio comedy. Billy Wilder’s mix of cynicism and warmth hinted at the morally messier adult stories that would dominate the 1970s. It showed studios that you could talk frankly abou intimacy, power and exploitation without losing the mainstream crowd.

Screenshot from The Apartment, United Artists

Screenshot from The Apartment, United Artists

Once Upon A Time In The West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West feels like a Western and a funeral for the Western at the same time. Sergio Leone stretches time, heightens danger and uses silence as dramatically as gunfire, turning a familiar genre into an operatic tragedy. Its influence on later revisionist Westerns and modern action films is enormous.

Screenshot from Once Upon A Time In The West, Paramount Pictures

Screenshot from Once Upon A Time In The West, Paramount Pictures

Night Of The Living Dead (1968)

Night of the Living Dead was low-budget, independently made and completely revolutionary. Its bleak ending, gore and casting of a Black lead without commentary created a new kind of political horror almost by accident. The film quietly taught Hollywood that small, daring genre projects could unleash huge cultural ripples—and massive profits later.

Screenshot from Night Of The Living Dead, Continental Distributing

Screenshot from Night Of The Living Dead, Continental Distributing

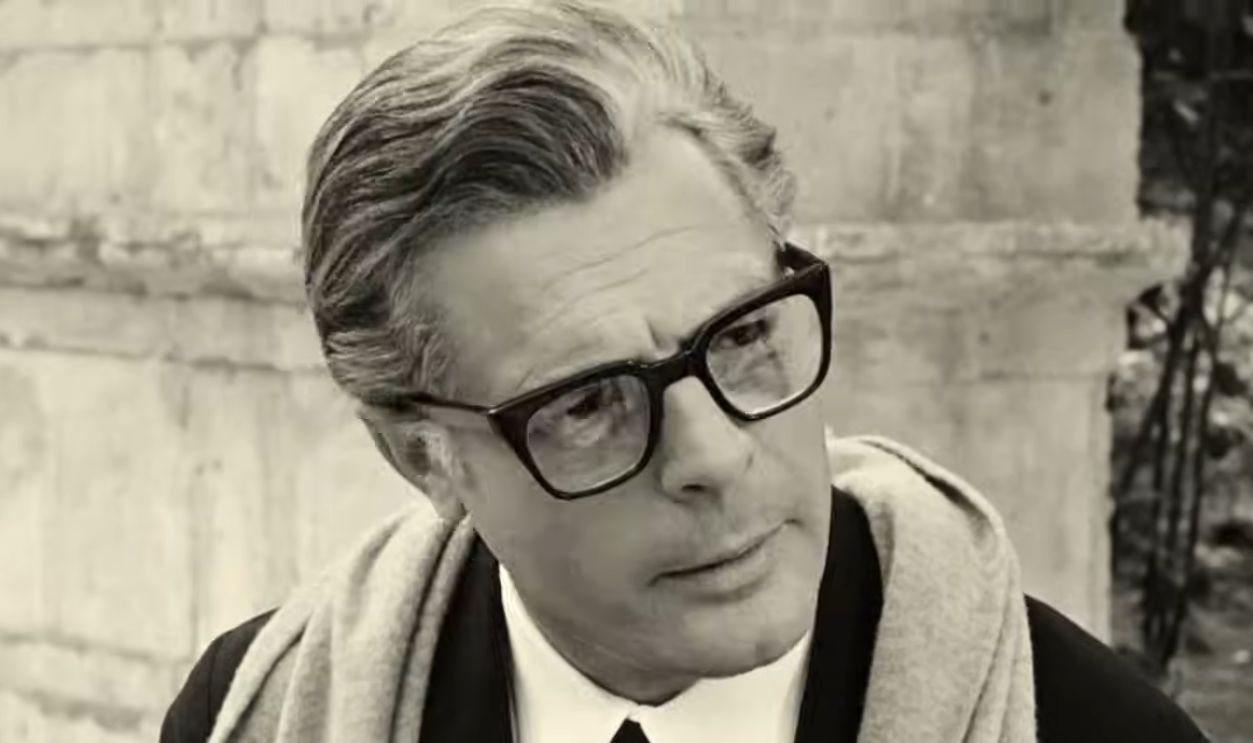

8½ (1963)

With 8½, Fellini turned creative burnout into a surreal circus of memory, fantasy and self-loathing. The movie’s free-floating, dreamlike structure became a touchstone for filmmakers trying to mix introspection with spectacle. Every Hollywood “auteur drama” about artists, directors or writers having breakdowns is, in some way, living in its shadow.

Screenshot from 8½, Columbia Pictures

Screenshot from 8½, Columbia Pictures

Mary Poppins (1964)

Mary Poppins was a giant leap forward for family filmmaking, blending live action and animation with technical polish and emotional heft. It cemented the idea that a “kids’ movie” could be a full-blown prestige release with awards buzz and serious adult appeal. Disney’s modern template—four-quadrant, effects-heavy musicals with franchise potential—starts right here on that London rooftop.

Screenshot from Mary Poppins, Walt Disney Pictures

Screenshot from Mary Poppins, Walt Disney Pictures

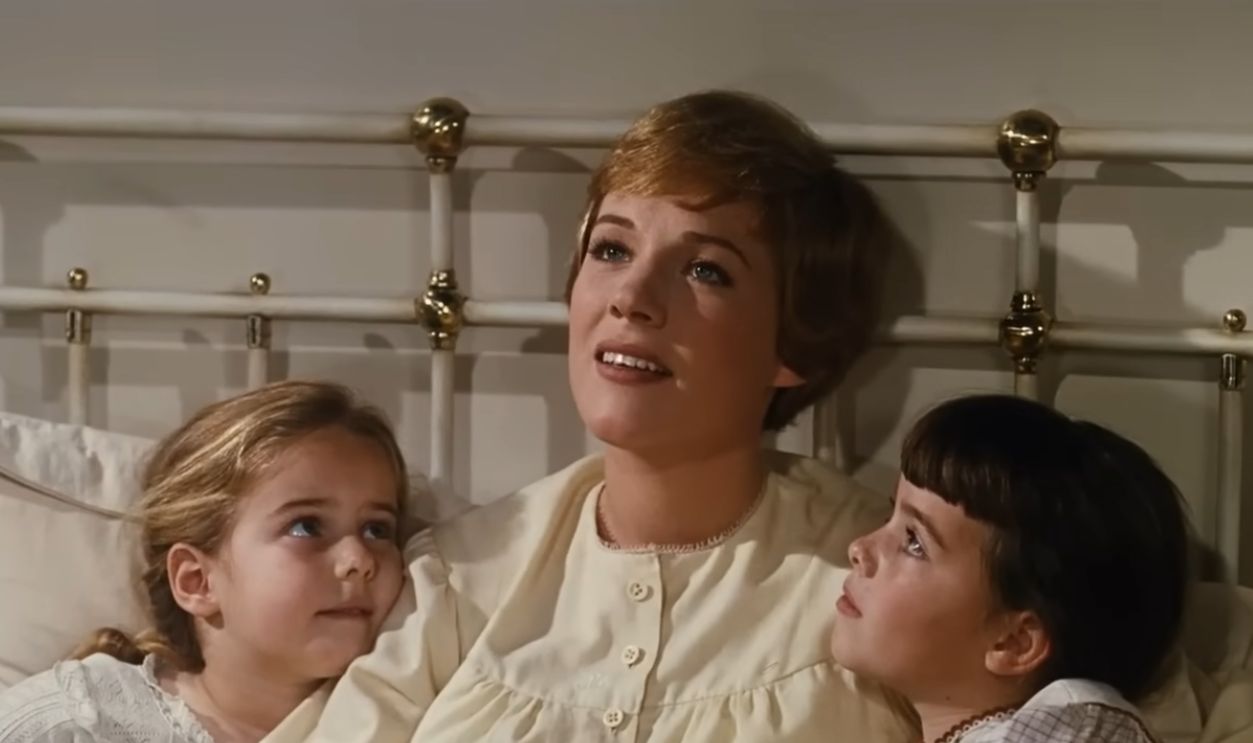

The Sound Of Music (1965)

The Sound of Music wasn’t just a hit; it was a cultural takeover. Its massive box office and enduring rewatch value taught studios that sentimental, lavishly produced crowd-pleasers could become long-term money machines. At the same time, its saccharine reputation helped spur younger filmmakers to push against that kind of safe, wholesome storytelling in the late 60s and 70s.

Screenshot from The Sound of Music, 20th Century Fox

Screenshot from The Sound of Music, 20th Century Fox

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

Cool Hand Luke gave Hollywood one of its defining antiheroes—a charming, doomed rebel who refuses to bend to authority. The film’s setting and casual brutality reflected the decade’s growing mistrust of institutions. From 70s outlaw icons to modern prestige-TV protagonists, Luke’s DNA is everywhere.

Screenshot from Cool Hand Luke, Warner Bros. Pictures

Screenshot from Cool Hand Luke, Warner Bros. Pictures

Playtime (1967)

Playtime turns a hyper-modern city into a giant, glass-and-steel slapstick machine. Jacques Tati’s obsession with environment, background gags and wide-angle choreography feels like an ancestor to today’s effects-heavy worldbuilding. While it nearly bankrupted its creator, the film pushed cinematic design to such an extreme that Hollywood production designers have been quietly stealing from it ever since.

Screenshot from Playtime, SN Prodis

Screenshot from Playtime, SN Prodis

Le Samouraï (1967)

Le Samouraï distilled the hitman genre into a pure mood: a silent killer, a minimalist apartment, endless trench coats and rain. Its stripped-down plotting and cool, blue-gray aesthetic became a style bible for crime cinema. You can see its fingerprints on everything from 80s neo-noirs to modern action franchises built around taciturn professionals and neon-lit melancholy.

Screenshot from Le Samourai, S.N. Prodis

Screenshot from Le Samourai, S.N. Prodis

The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg (1964)

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is an all-sung melodrama that looks like a candy box and feels like heartbreak. Its bold color design, through-composed music and bittersweet ending pushed the musical genre into more emotionally complex territory. Modern Hollywood musicals that play with nostalgia while quietly breaking your heart owe a huge debt to this little shop in Cherbourg.

Screenshot from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, 20th Century Fox

Screenshot from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, 20th Century Fox

Final Thoughts

These 21 films didn’t just define the 60s—they cracked open the possibilities of what movies could be, who they could be for and how far studios were willing to go. Modern Hollywood, with all its contradictions and ambitions, is still living in their long, very stylish shadow.

Screenshot from The Sound of Music, 20th Century Fox

Screenshot from The Sound of Music, 20th Century Fox

You May Also Like:

The Best "One-Room" Movies That Keep You Glued To The Screen

Movies That Capture Nostalgia Without Feeling Fake

Films That Were Secretly Allegories For Real Events

Source: 1