Top 30 From the ‘70s

This isn’t a terribly controversial opinion, but I’m going to say it anyway: the 1970s were the best decade for movies. Ever.

And yet, a lot of “Best of the 70s” lists still get it wrong. Sure, there are a handful of titles that always show up—and always deserve to. But there are too many others that don’t get nearly the respect they should. So I’ve decided to fix that right now.

No ranking, because that’s a whole other argument—and that’s not the point here. The point is simple: pick the 30 best films from the best movie decade. And here they are (again, in no particular order)…

“The Godfather” (1972)

They aren’t all going to be this obvious, but… come on. The Godfather is great—and just one of Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpieces from the decade (spoiler: he’ll show up a few more times).

Screenshot from The Godfather, Paramount Pictures (1972)

Screenshot from The Godfather, Paramount Pictures (1972)

“The Godfather Part II” (1974)

No, Coppola isn’t the only director on my list, but if I was starting with The Godfather, it only made sense to get Part II in there right afterwards. Is it possible the sequel is even better than the first one? People have been arguing about this for decades, so I’ll just politely step back now.

Screenshot from The Godfather II, Paramount Pictures (1974)

Screenshot from The Godfather II, Paramount Pictures (1974)

“The Sting” (1973)

Sometimes a movie is just allowed to be fun—and The Sting is extremely good at it. Newman and Redford have ridiculous chemistry, the con is clever without being smug, and everything clicks exactly when it should.

Screenshot from The Sting, Universal (1973)

Screenshot from The Sting, Universal (1973)

“Sleuth” (1972)

Sleuth is two people trying to intellectually destroy each other for two straight hours, and it is spectacular. Michael Caine and Laurence Olivier spend the entire film trading insults, mind games, and power moves—and it’s wildly entertaining (and wildly underappreciated). A must-see.

Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

“Taxi Driver” (1976)

Yes, I’m looking at you, Taxi Driver. And I’m calling you one of the 30 best films of the 70s. It’s not an easy watch—but that’s not what Scorsese was going for, now was it?

Screenshot from Taxi Driver, Columbia Pictures (1976)

Screenshot from Taxi Driver, Columbia Pictures (1976)

“Jaws” (1975)

Yes, this is a movie about a shark. But as those of us who’ve seen it multiple times know, the shark is barely on screen for most of the film. And yet Spielberg somehow managed to make all of us afraid of the ocean for the next 50 years. Also, raise your hand if you can get on any kind of water vessel without saying, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.” Yeah—didn’t think so.

Screenshot from Jaws, Universal Pictures (1975)

Screenshot from Jaws, Universal Pictures (1975)

“Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” (1975)

Yes, it’s slow. Yes, it’s long. Yes, that’s the whole point. And yes, it’s brilliant. Jeanne Dielman turns routine into tension and makes tiny disruptions feel massive. If we’re talking about the 70s pushing cinema forward, this one belongs in that conversation whether people are ready for it or not.

Screenshot from Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, Paradise (1975)

Screenshot from Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, Paradise (1975)

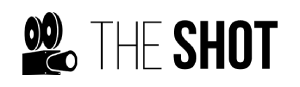

“Apocalypse Now” (1979)

This movie feels like it was barely held together with duct tape and sheer willpower—and honestly, if you’ve seen Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, it kinda was. Apocalypse Now doesn’t explain itself, it doesn’t clean anything up, and by the end you’re just sitting there thinking, “Well… that was a lot.”

Screenshot from Apocalypse Now, United Artists (1979)

Screenshot from Apocalypse Now, United Artists (1979)

“Chinatown” (1974)

This movie slowly convinces you it’s a clever mystery—and then casually reminds you that none of that really matters. Chinatown doesn’t offer justice, closure, or comfort. It just shrugs and says, “Yeah, that’s how it works.” That ending still hits because it refuses to pretend otherwise.

Screenshot from Chinatown, Paramount (1974)

Screenshot from Chinatown, Paramount (1974)

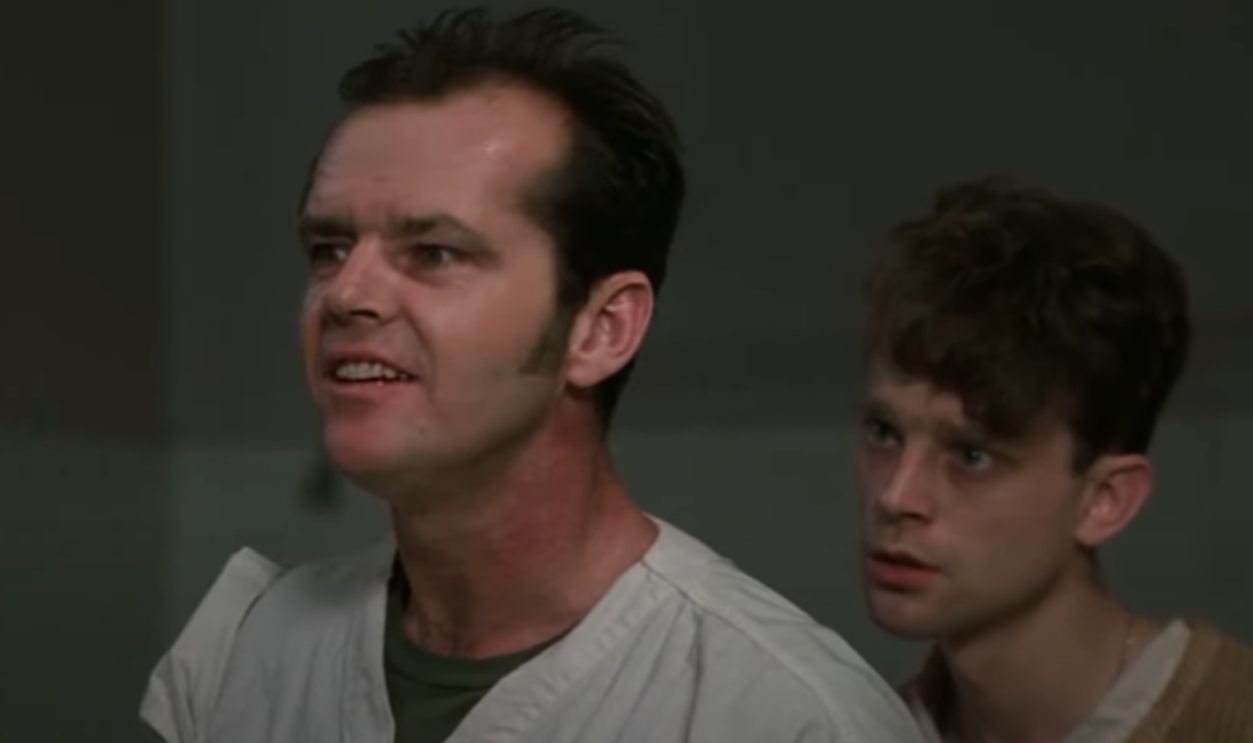

“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975)

A lot of people remember this as inspiring, and then rewatch it and go, “Oh… right.” One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is funny, yes—but it’s also angry and quietly devastating. Jack Nicholson pulls you in with charm before the movie slowly tightens the screws. By the end, it hits way harder than you expect.

Screenshot from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, United Artists (1975)

Screenshot from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, United Artists (1975)

“The French Connection” (1971)

This movie doesn’t care if you like anyone in it—and that’s part of the appeal. The French Connection is grimy, tense, and constantly moving forward, like it’s late for something. Yes, the car chase is legendary, but the real takeaway is how rough and unsentimental everything feels. Very early-70s. Zero polish. All confidence.

Screenshot from The French Connection, 20th Century-Fox (1971)

Screenshot from The French Connection, 20th Century-Fox (1971)

“Rocky” (1976)

People forget this is actually a pretty small, personal movie. Rocky isn’t about becoming the champ—it’s about proving something to yourself when no one else is paying attention. Have you run up the steps at the Philadelphia Museum of Art yet?

Screenshot from Rocky, United Artists (1976)

Screenshot from Rocky, United Artists (1976)

“The Exorcist” (1973)

The Exorcist isn’t just a great horror film. It’s a great film that happens to be horror. The 70s knew—and appreciated—that difference. It never winks at the audience. No shortcuts, no irony—just dread slowly building until it’s unavoidable.

Screenshot from The Exorcist, Warner Bros.(1973)

Screenshot from The Exorcist, Warner Bros.(1973)

“Network” (1976)

Every year this movie somehow feels less like satire and more like a documentary, which is… kinda scary. Network understood media outrage, performative yelling, and people mistaking volume for truth long before social media made it unavoidable.

Screenshot from Network, MGM (1976)

Screenshot from Network, MGM (1976)

“Badlands” (1973)

Terrence Malick doesn’t exactly flood the market with movies. He makes one every so often, disappears for years, then casually reminds everyone he’s Terrence Malick. And Badlands was his first—his debut film. And you can see its fingerprints all over later “young lovers on the run” movies.

Screenshot from Badlands, Warner Bros. Pictures (1973)

Screenshot from Badlands, Warner Bros. Pictures (1973)

“Monty Python and the Holy Grail” (1975)

Some movies age. This one just keeps yelling, “It’s just a flesh wound!” and moving on. Monty Python and the Holy Grail ignores logic, structure, and good taste—and that’s exactly why it works. The jokes still land, the quotes never stop, and if someone says, “Your father smelt of elderberries,” you know exactly what they’re talking about (even though none of us actually know what an elderberry is).

Screenshot from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Sony Pictures (1975)

Screenshot from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Sony Pictures (1975)

“The Conversation” (1974)

Coppola’s fourth masterpiece of the decade… The Conversation. Smaller, quieter, and way more paranoid than his mob epics or his Vietnam fever dream, this one proves he didn’t need operatic drama to make something great. It’s controlled, tense, and built almost entirely on unease. Not flashy. Just excellent.

Screenshot from The Conversation, Paramount Pictures (1974)

Screenshot from The Conversation, Paramount Pictures (1974)

“Kramer vs. Kramer” (1979)

This is one of those movies people assume will feel dated—and then it absolutely doesn’t. Kramer vs. Kramer doesn’t turn divorce into a villain origin story. There’s no mustache-twirling bad guy. Just two people trying (and sometimes failing) to figure out what being a parent looks like when everything changes. It’s quiet, uncomfortable, and still hits harder than you expect.

Screenshot from Kramer vs. Kramer, Columbia Pictures (1979)

Screenshot from Kramer vs. Kramer, Columbia Pictures (1979)

“Alien” (1979)

This is a horror movie pretending to be sci-fi, and that’s why it works so well. It’s slow, tense, and doesn’t explain anything it doesn’t have to. Also, Ripley becoming the best character in the movie feels completely natural—not like the script suddenly remembered she was there.

Screenshot from Alien, 20th Century Fox (1979)

Screenshot from Alien, 20th Century Fox (1979)

“Dog Day Afternoon” (1975)

What starts as a robbery slowly turns into a circus, and somehow that makes it even more stressful. Dog Day Afternoon is funny, chaotic, sad, and completely unpredictable. Pacino is doing Pacino things, but the real hook is watching everything spiral in public, in real time. Also, once you hear “Attica!” you never forget it.

Screenshot from Dog Day Afternoon, Warner Bros. (1975)

Screenshot from Dog Day Afternoon, Warner Bros. (1975)

“The Deer Hunter” (1978)

Michael Cimino swung big with The Deer Hunter, and it paid off. It’s intense, emotional, and absolutely not in a hurry. The movie takes its time before it hits—and when it does, it really does. Of course, Cimino’s next film was Heaven’s Gate, which became one of the most infamous flops in Hollywood history. But there’s no denying this one deserves to be here.

Screenshot from The Deer Hunter, Universal Pictures (1978)

Screenshot from The Deer Hunter, Universal Pictures (1978)

“Barry Lyndon” (1975)

Barry Lyndon isn’t just beautiful to look at. It’s cold, funny, and quietly brutal. It might not be as instantly recognizable as 2001 or Dr. Strangelove, but it is well deserving of its place here.

Screenshot from Barry Lyndon, Warner Bros. (1975)

Screenshot from Barry Lyndon, Warner Bros. (1975)

“Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977)

Before aliens were mostly about blowing up landmarks, Spielberg gave us obsession and wonder. Close Encounters isn’t cynical—it’s sincere, and completely committed to that sense of awe. Also, if you’ve ever looked at a plate of mashed potatoes and briefly considered sculpting a mountain, you already know how powerful this movie is. Admit it.

Screenshot from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Columbia (1977)

Screenshot from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Columbia (1977)

“Serpico” (1973)

A movie about doing the right thing and watching it backfire. Pacino’s Serpico isn’t rewarded for his integrity—he’s punished for it. And in case you weren't counting—That's 3 movies on my list from the great (and often overlooked) Sidney Lumet.

Screenshot from Serpico, Paramount Pictures (1973)

Screenshot from Serpico, Paramount Pictures (1973)

“All the President’s Men” (1976)

On paper, this movie sounds like homework. Two reporters make phone calls and knock on doors. Riveting stuff, right? And yet All the President’s Men is somehow gripping the entire time. It proves that tension doesn’t need explosions—it just needs stakes, Robert Redford, and Dustin Hoffman.

Screenshot from All The President’s Men, Warner Bros. (1976)

Screenshot from All The President’s Men, Warner Bros. (1976)

“Mean Streets” (1973)

This is Scorsese figuring things out in real time. Loud, messy, personal, and full of raw energy. You can practically see the rest of his career forming in front of you.

Screenshot from Mean Streets, Warner Bros. (1973)

Screenshot from Mean Streets, Warner Bros. (1973)

“Manhattan” (1979)

Beautifully shot, very New York, and packed with relationship neuroses. Manhattan isn’t just the title of the film, or the location, the brilliant cinematography makes it a character in the movie, as important as any of the people (maybe even more so).

Screenshot from Manhattan, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) (1979)

Screenshot from Manhattan, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) (1979)

“Being There” (1979)

Being There might be the calmest satire ever made—and that’s exactly why it works. Peter Sellers barely does anything, says almost nothing, and somehow gets treated like a genius. Sound kinda familiar? I’ve always thought of Forrest Gump as the poor man’s Being There. Quiet movie. Big point.

Screenshot from Being There, United Artists(1979)

Screenshot from Being There, United Artists(1979)

“Annie Hall” (1977)

Relationships are messy. They don’t wrap up neatly. And sometimes the timing is just… off. Annie Hall understood that before most romantic comedies did. It’s funny, awkward, self-aware—and bold enough to literally pull Marshall McLuhan out from behind a movie theater poster just to win an argument. Honestly, we’ve all wished we could do that at least once (at least those of us who know who Marshall McLuhan was).

Screenshot from Annie Hall, United Artists (1977)

Screenshot from Annie Hall, United Artists (1977)

“Straw Dogs” (1971)

This is one of the most confrontational films of the entire decade—and it’s meant to be. If all you know is the 2011 remake, then sure, this pick probably won’t make sense. Unlike the mediocre remake, Sam Peckinpah’s original is colder, harsher, and far more unsettling—although it is well settled on my list (sorry, that was terrible).

Screenshot from Straw Dogs, 20th Century Fox (1971)

Screenshot from Straw Dogs, 20th Century Fox (1971)

You Might Also Like:

Quiz: Can You Match the Quote to the Movie?

Movies That Prove Cinema Is Better Than Every Other Art Form