The One Scene That Changed The Formula

Some moments don’t announce themselves. A single look, a cut, a pause. Suddenly, movies felt different, and the rules everyone expected quietly stopped applying.

Shower Murder: Psycho

Fast edits and piercing music transformed an ordinary bathroom into a nerve-racking space. Hitchcock relied on implication rather than explicit imagery, reshaping suspense filmmaking and proving that audience imagination could generate fear more powerfully than on-screen violence.

Screenshot from Psycho, Universal Pictures (1960)

Screenshot from Psycho, Universal Pictures (1960)

Bullet Time Lobby Shootout: The Matrix

Time appears suspended as the camera moves freely through the exhilarating action. Bullet time, where Neo bends backward to dodge bullets in slow motion, blended still photography with digital stitching, and it introduced a new visual grammar that rebranded fight choreography.

Screenshot from The Matrix, Warner Bros. Pictures (1999)

Screenshot from The Matrix, Warner Bros. Pictures (1999)

Opening Beach Landing: Saving Private Ryan

The sequence in this legendary scene used handheld cameras, altered shutter speed, and desaturated color to simulate battlefield perception. The producer, Spielberg, removed the overused heroic framing in the genre. Later war films such as Black Hawk Down adopted this documentary approach.

Screenshot from Saving Private Ryan, DreamWorks Pictures (1998)

Screenshot from Saving Private Ryan, DreamWorks Pictures (1998)

Star Destroyer Flyover: Star Wars

The opening shot in Star Wars extends far longer than typical establishing images. Duration communicates scale before the story, and this technique influenced later science fiction openings. Blockbusters began using visual size as narrative context rather than relying on exposition or dialogue to establish world scope.

Screenshot from Star Wars, 20th Century Fox (1977)

Screenshot from Star Wars, 20th Century Fox (1977)

Jump Cut Montage: Breathless

In this technique, scenes advance abruptly without traditional continuity. American films, including Bonnie and Clyde, followed. Jump cuts moved from mistake to style. Narrative pacing became more flexible, and modern cinema embraced fragmentation as a deliberate storytelling device.

Screenshot from Breathless, Les Films Imperia (1960)

Screenshot from Breathless, Les Films Imperia (1960)

Match Cut Bone To Satellite: 2001: A Space Odyssey

This movie introduced a scene where one cuts links from prehistoric tools to space technology. Kubrick compressed historical progression visually, and other film producers took this up as symbolic editing. Science fiction expanded beyond plot mechanics and began addressing philosophical ideas through visual association instead of explanation.

Screenshot from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1968)

Screenshot from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1968)

Odessa Steps Massacre: Battleship Potemkin

Emotion emerges through shot arrangement even before you note the character psychology. This was montage theory in practice, and it influenced sequences like The Untouchables staircase scene. Editing became the primary driver of tension, shaping how suspense and movement function across narrative cinema.

Screenshot from Battleship Potemkin, Goskino (1925)

Screenshot from Battleship Potemkin, Goskino (1925)

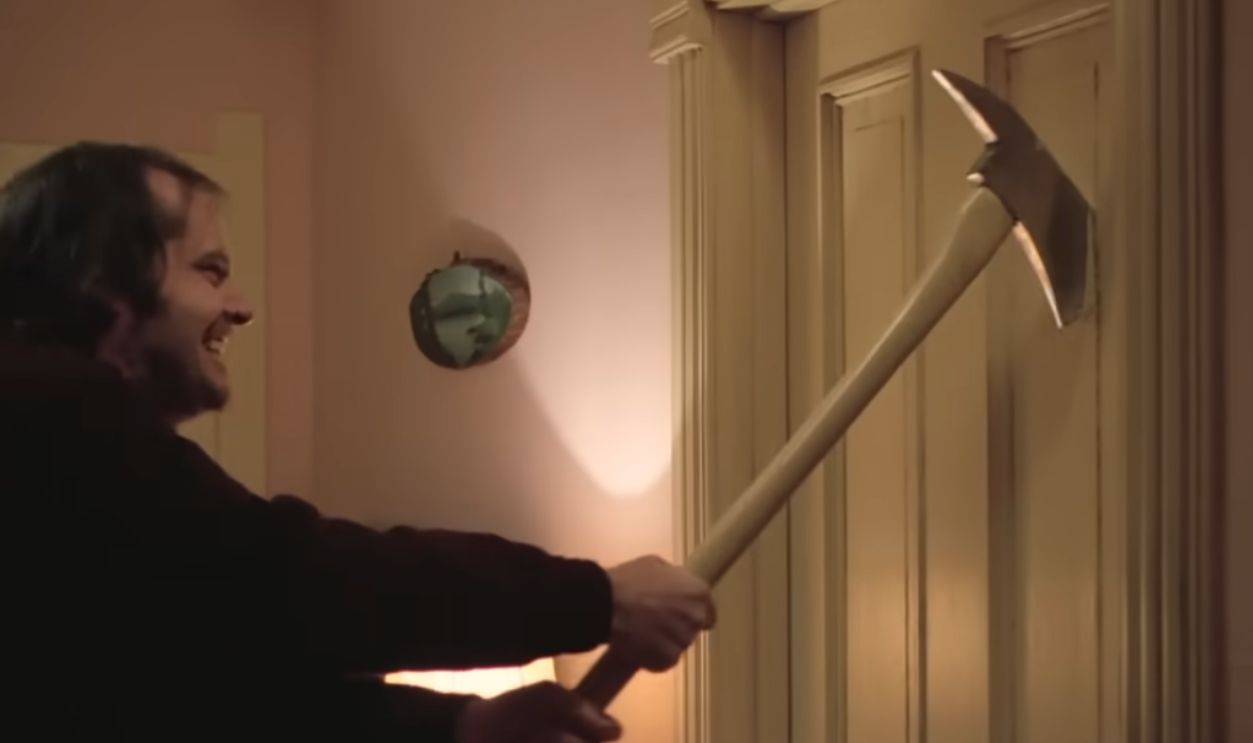

Axe Through The Door: The Shining

The scene emphasizes framing and duration over sudden shock, where the producer, Kubrick, prioritized spatial pressure. The horror films that followed this one also maintained this restraint. From then on, genre storytelling shifted toward sustained psychological tension, not just rapid scares or aggressive editing patterns.

Screenshot from The Shining, Warner Bros. Pictures (1980)

Screenshot from The Shining, Warner Bros. Pictures (1980)

T-Rex Breakout: Jurassic Park

In this scene, animatronics and computer graphics share the screen under controlled lighting. Digital elements earned narrative credibility, allowing visual effects to carry character interaction and story importance within mainstream cinema. Effects-driven films like King Kong followed this model.

Screenshot from Jurassic Park, Universal Pictures (1993)

Screenshot from Jurassic Park, Universal Pictures (1993)

Baptism Assassination Montage: The Godfather

Here, post-production used contrast as structure. The parallel editing connected a religious ritual with coordinated murders. It was so influential that most crime films, including Goodfellas, borrowed this leaf. Editing conveyed moral themes directly, and it changed how power and hypocrisy appeared in American gangster narratives.

Screenshot from The Godfather, Paramount Pictures (1972)

Screenshot from The Godfather, Paramount Pictures (1972)

Final Freeze Frame: The 400 Blows

The film ends with a sudden freeze, not a resolution. That choice influenced New Hollywood filmmakers, as seen in pictures like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Endings stopped explaining meaning and began trusting audiences to interpret emotional consequences on their own.

Screenshot from The 400 Blows, Les Films du Carrosse (1959)

Screenshot from The 400 Blows, Les Films du Carrosse (1959)

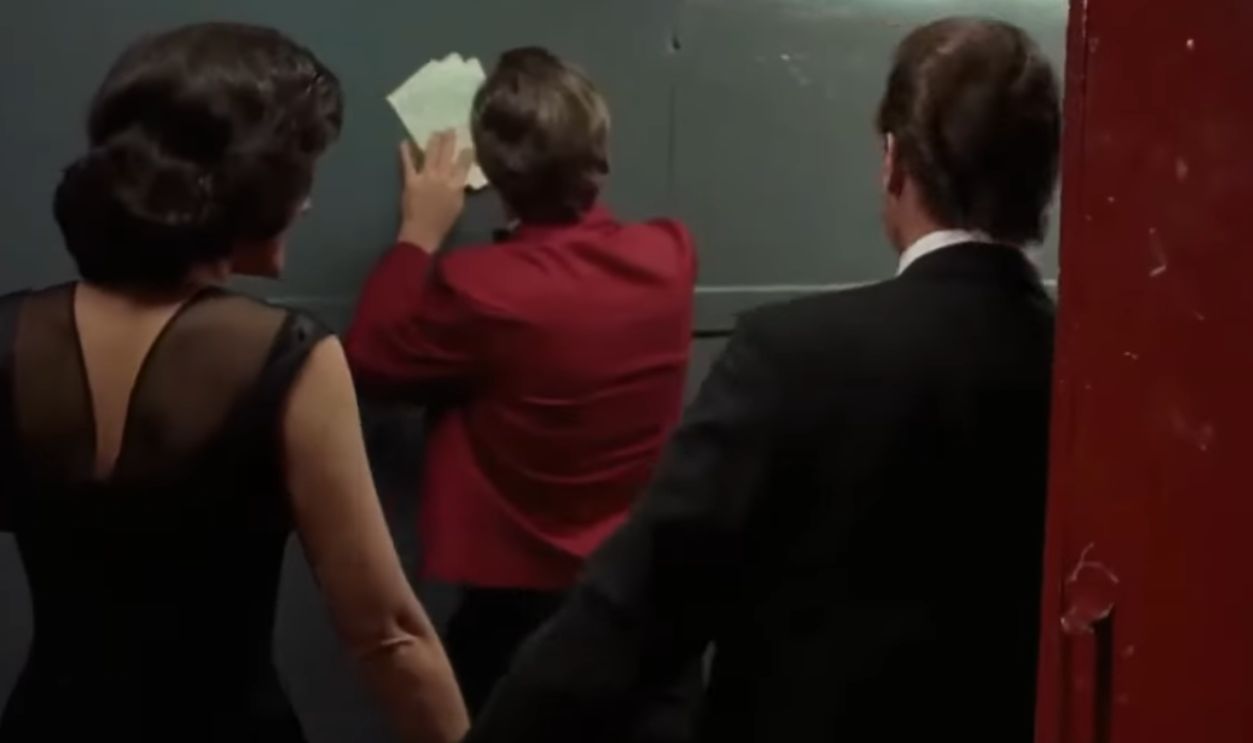

Louvre Run: Band Of Outsiders

Later films learned that tone could come from motion. Godard proved it by sending characters sprinting through a museum without reverence. Art lost its formality. Energy replaced careful composition, showing spontaneity could shape mood more effectively than narrative justification.

Screenshot from Band of Outsiders, Janus Films (1964)

Screenshot from Band of Outsiders, Janus Films (1964)

Opening Robbery: Bonnie And Clyde

Bonnie and Clyde started with a bang, where violence appeared sudden and personal. Penn reframed crime with emotional realism, and as a result, the American cinematic scene shifted tone. Gunfights became unsettling experiences, and this reshaped how consequences appeared on screen during the late 1960s.

Screenshot from Bonnie and Clyde, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts (1967)

Screenshot from Bonnie and Clyde, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts (1967)

First Color Reveal: The Wizard Of Oz

Sepia gives way to Technicolor without explanation. Color became a narrative device. After The Wizard of Oz did it, a couple of more fantasy films adopted the technique. Cinema learned aesthetics could guide story understanding as clearly as dialogue or plot mechanics.

Screenshot from The Wizard of Oz, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

Screenshot from The Wizard of Oz, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

“Tears In Rain” Monolog: Blade Runner

The speech reframed artificial life as an emotional concept. Science fiction slowed its pace. Genre storytelling turned inward. Action stepped aside for reflection, as characters openly questioned existence and pushed the genre beyond technology toward philosophical identity.

Screenshot from Blade Runner, Warner Bros. Pictures (1982)

Screenshot from Blade Runner, Warner Bros. Pictures (1982)

Copacabana Tracking Shot: Goodfellas

Uninterrupted movement carries the camera through the restaurant entrance, turning motion into meaning. Scorsese made that flow a marker of status, and this gave long takes a narrative purpose. Other films followed, using camera placement to signal power and access.

Screenshot from Goodfellas, Warner Bros. Pictures (1990)

Screenshot from Goodfellas, Warner Bros. Pictures (1990)

Train Arrival: L’Arrivee D’un Train

Audiences became captivated by motion itself. The scene framed cinema as an experience. Early filmmakers recognized that realism mattered, allowing narrative to grow beyond spectacle. That shift defined film as separate from theater, driven by movement.

Screenshot from L’Arrivee d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, Lumiere Brothers (1896)

Screenshot from L’Arrivee d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, Lumiere Brothers (1896)

Split-Screen Climax: Carrie

Horror began using formal experimentation to convey inner collapse. After this, production turned to stylistic tools instead of relying on performance or dialogue. De Palma crystallized the shift by splitting the screen during the prom massacre, and he made the visualization of emotional fracture felt in real time.

Screenshot from Carrie, United Artists (1976)

Screenshot from Carrie, United Artists (1976)

Diner Opening: Pulp Fiction

The film opens mid-conversation, and it signaled a playful shift in structure. Nonlinear storytelling reached mainstream audiences. Chronology lost authority and narrative order took over, becoming the creative choice in popular cinema.

Screenshot from Pulp Fiction, Miramax Films (1994)

Screenshot from Pulp Fiction, Miramax Films (1994)

Mirror Monolog: Taxi Driver

Cinema began placing subjective experience at the center of narrative rather than the external plot. For a change, antiheroes gained prominence. Scorsese advanced that shift in Taxi Driver by turning the camera inward, letting a character address himself, and exposing an unstable perspective directly.

Screenshot from Taxi Driver, Columbia Pictures (1976)

Screenshot from Taxi Driver, Columbia Pictures (1976)

Final Zoom On The Bus: The Graduate

Uncertainty replaces celebration during the closing shot on a moving bus. Romantic resolution disappears, and just like that, the typical Hollywood endings shifted tone. The Graduate was among the first movies to encourage filmmakers to leave stories emotionally unresolved.

Screenshot from The Graduate, Embassy Pictures (1967)

Screenshot from The Graduate, Embassy Pictures (1967)

Car Ambush Long Take: Children Of Men

Alfonso Cuaron used continuity as a narrative force in Children of Men. Here, tension built through uninterrupted action instead of cutting. Extended takes gained legitimacy, shaping films like 1917, where sustained perspective replaced montage as the primary method for suspense and immersion.

Screenshot from Children of Men, Universal Pictures (2006)

Screenshot from Children of Men, Universal Pictures (2006)

Opening Tracking Shot: Touch Of Evil

Directors began using movement to establish tone and danger before dialogue appeared. Orson Welles proved camera motion could carry narrative information in Touch of Evil. Openings evolved, with filmmakers such as Scorsese favoring tracking shots over exposition or static framing to set momentum immediately.

Screenshot from Touch of Evil, Universal-International Pictures (1958)

Screenshot from Touch of Evil, Universal-International Pictures (1958)

Zero Gravity Hallway Fight: Inception

Large-scale action regained credibility when physical rules guided spectacle. Digital shortcuts faded as priorities shifted. Other blockbusters followed, with films such as Mission: Impossible–Fallout emphasizing weight, balance, and spatial logic.

Screenshot from Inception, Warner Bros. Pictures (2010)

Screenshot from Inception, Warner Bros. Pictures (2010)

Burning Plantation Escape: Gone With The Wind

Scale supports the story without overwhelming it. Characters remain central amid destruction. Gone with the Wind shaped epic filmmaking. Historical dramas like Doctor Zhivago embraced massive production values as emotional amplifiers, proving spectacle could deepen narrative stakes instead of distracting from them.

Screenshot from Gone with the Wind, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

Screenshot from Gone with the Wind, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)