Carlin's Comedy From Tragedy

George Carlin didn’t just tell jokes—he held up a mirror. He made people laugh at themselves, then think about why they were laughing. But in 1997, life hit him in a way that no punchline could fix. From then on, his comedy carried something raw. After that, his comedy wasn’t just funny—it was furious, and beneath the punchlines, you could feel something had cracked.

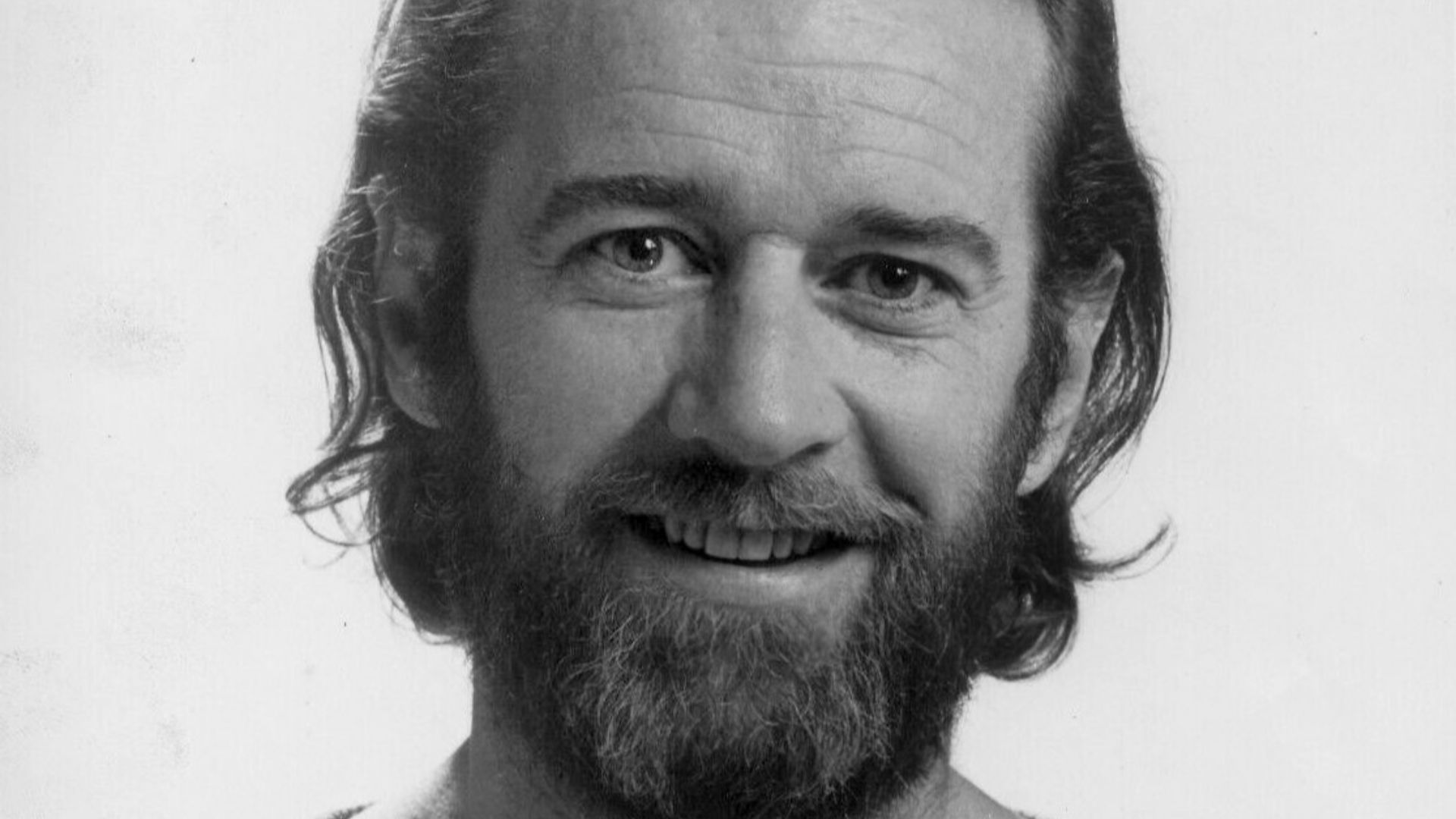

The Street Kid With A Sharp Tongue

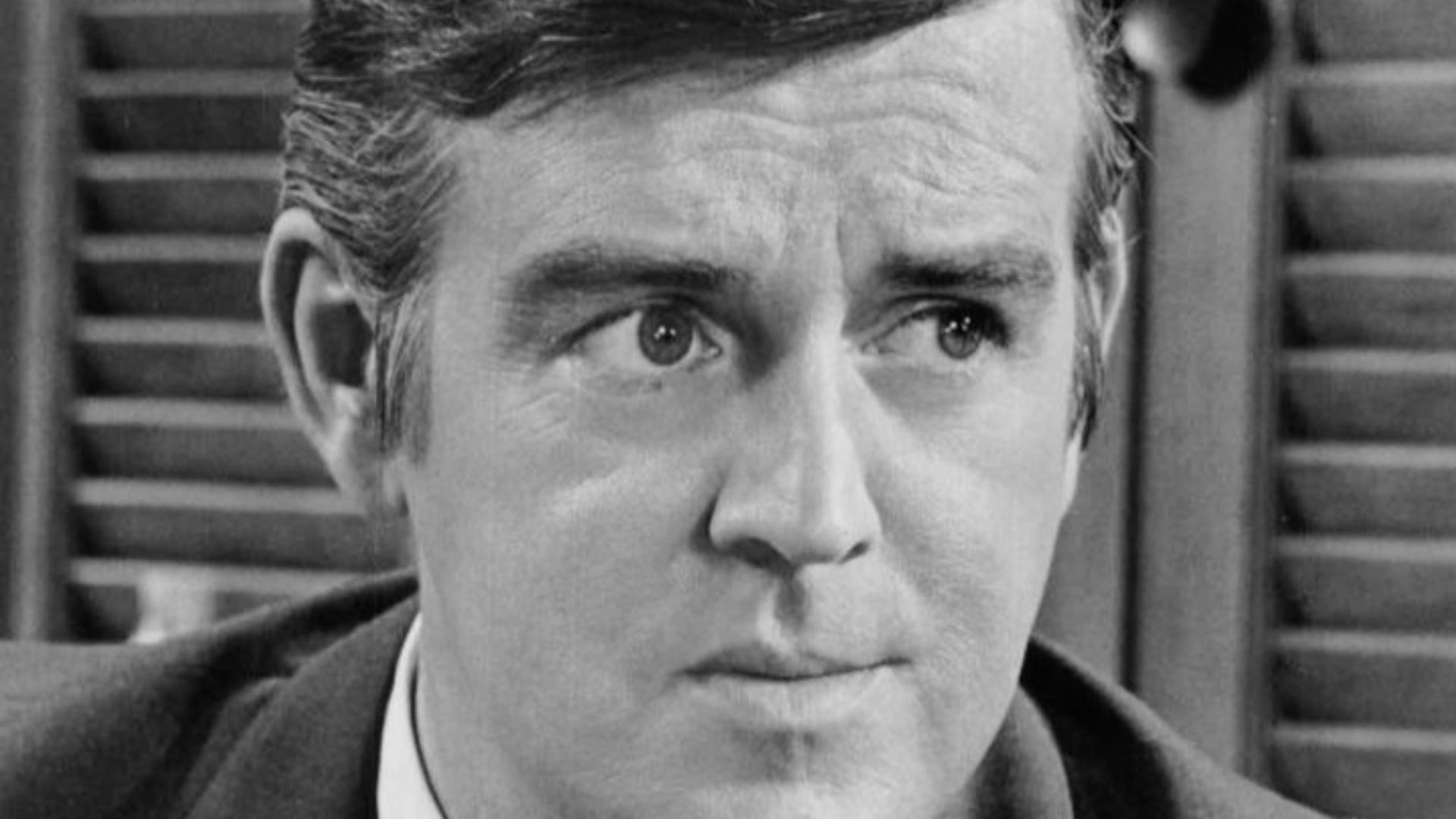

Born in 1937 in Manhattan, George Carlin grew up in a neighborhood that valued survival over sensitivity. His father struggled with drinking and left when George was just a baby, leaving his mother, Mary, to raise him alone. Carlin once said he got his “Irish anger” from his father and his “verbal precision” from his mother—two forces that would define his career.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Laughter As A Shield

Even as a kid, Carlin used humor to make sense of the chaos around him. At Catholic school, he became the class clown—mocking priests, rituals, and the endless rules. Years later, he admitted, “I had a very deep distrust of authority—especially people who claimed to speak for God.”

ABC Television, Wikimedia Commons

ABC Television, Wikimedia Commons

The Air Force Rebel

After dropping out of high school, Carlin joined the U.S. Air Force—probably not the ideal place for someone with such an anti-authority streak. It didn’t take long for that to get him in trouble. He was court-martialed three times for insubordination and eventually labeled “an unproductive airman.”

Radio, Jokes, and Jack Burns

After leaving the Air Force, Carlin worked as a DJ in Texas, where he met Jack Burns. Together they formed Burns and Carlin, a duo that mixed sharp wordplay with social satire. The act took off quickly, landing them gigs in Los Angeles and even a record deal. But Carlin was itching to go solo. The two stayed friends after the breakup, though—it was never personal.

ABC Television, Wikimedia Commons

ABC Television, Wikimedia Commons

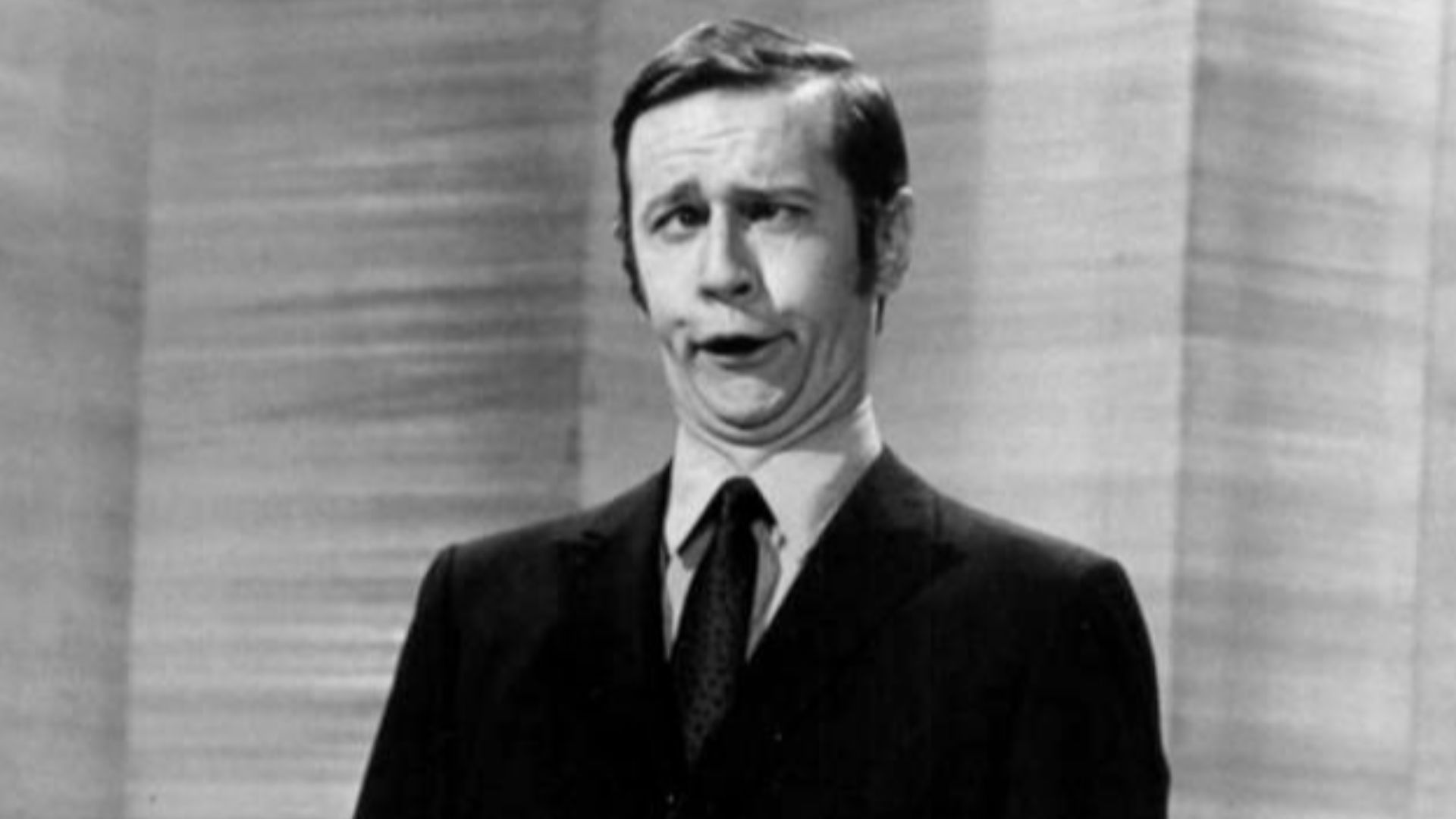

The Clean-Cut Comedian

In the 1960s, Carlin was a regular on The Ed Sullivan Show and The Tonight Show. He wore suits, smiled big, and told tidy little jokes about airline food and suburbia. The audiences loved him—but he didn’t love himself in that role. He once said, “”I didn’t want to be the next Merv Griffin. I wanted to say something.

CBS, The Ed Sullivan Show (1948 - 1971)

CBS, The Ed Sullivan Show (1948 - 1971)

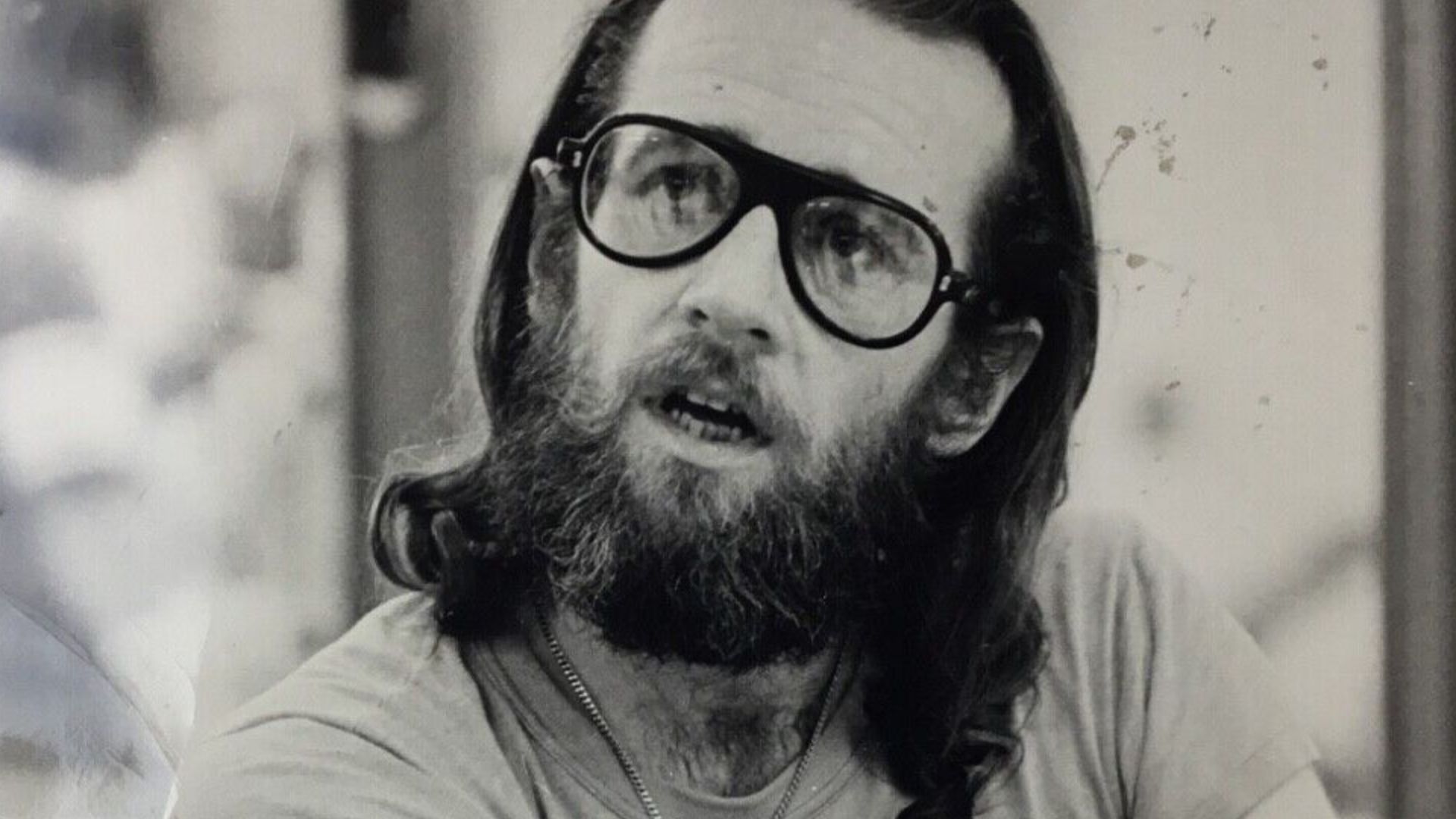

Breaking The Mold

By 1970, Carlin had had enough of clean-cut comedy. He grew his hair, tossed the suit, and started talking about what actually mattered—Vietnam, free speech, religion, and censorship. That shift turned some fans off but gained him a whole new audience that saw him as the voice of the counterculture.

The Christian Science Monitor News and Photo Service, Wikimedia Commons

The Christian Science Monitor News and Photo Service, Wikimedia Commons

“The Seven Words You Can Never Say On Television”

Carlin’s most notorious bit, “Seven Words You Can Never Say On Television,” didn’t just shock people—it changed U.S. law. When a New York radio station aired it, the FCC fined them, and the case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Carlin suddenly stood for free speech itself. As he put it, “The duty of the comedian is to find out where the line is—and cross it deliberately.”

George Carlin - 7 Words You Can't Say On TV, Thrivers

George Carlin - 7 Words You Can't Say On TV, Thrivers

Fame, Pressure, and Excess

The 1970s made him a superstar—and nearly destroyed him. Carlin later admitted he’d gotten caught up in the chaos of fame and was pushing his limits in every way possible. He was arrested for an obscenity charge in the early 1970s, hospitalized for heart trouble, and faced mounting financial stress during his peak touring years. But the same restlessness that fueled his habits also powered his creativity. And through it all, there was Brenda.

Brenda—The One Who Grounded Him

Carlin married Brenda Hosbrook in 1961, long before the fame. She managed his schedule, ran his business, and kept him focused when he was spiraling. He said simply, “She believed in me before I did.”

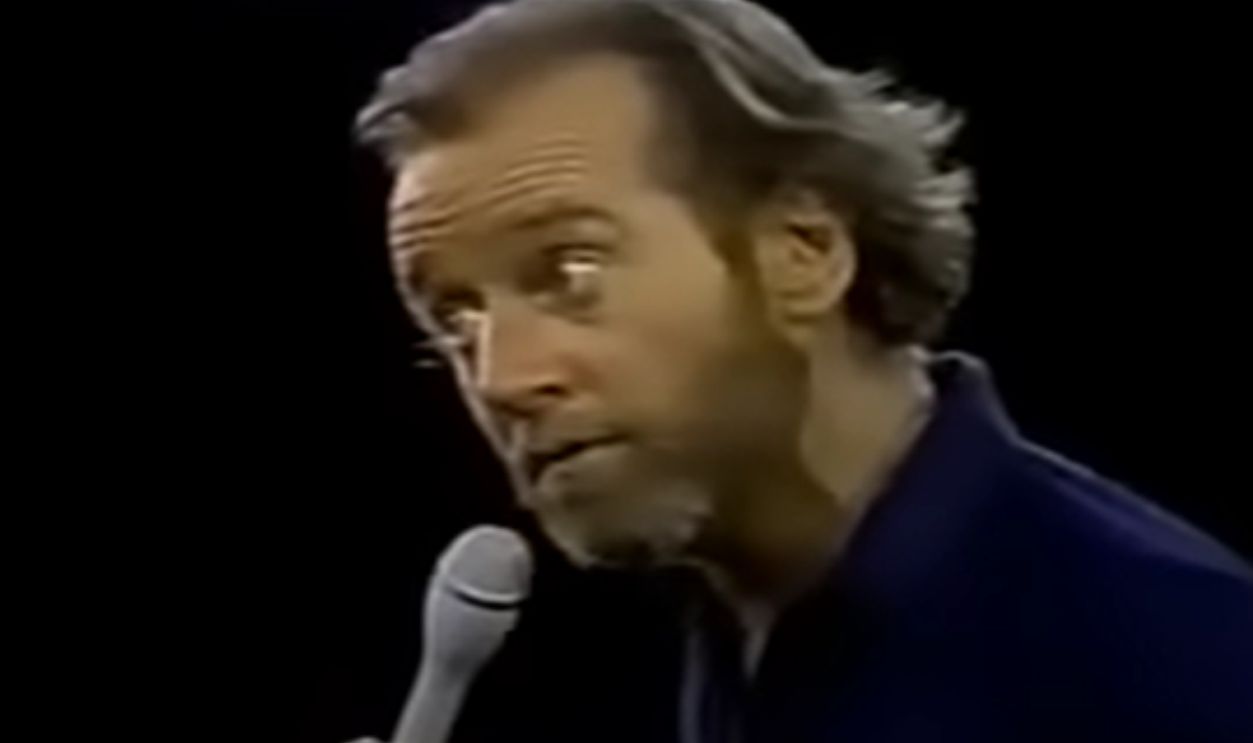

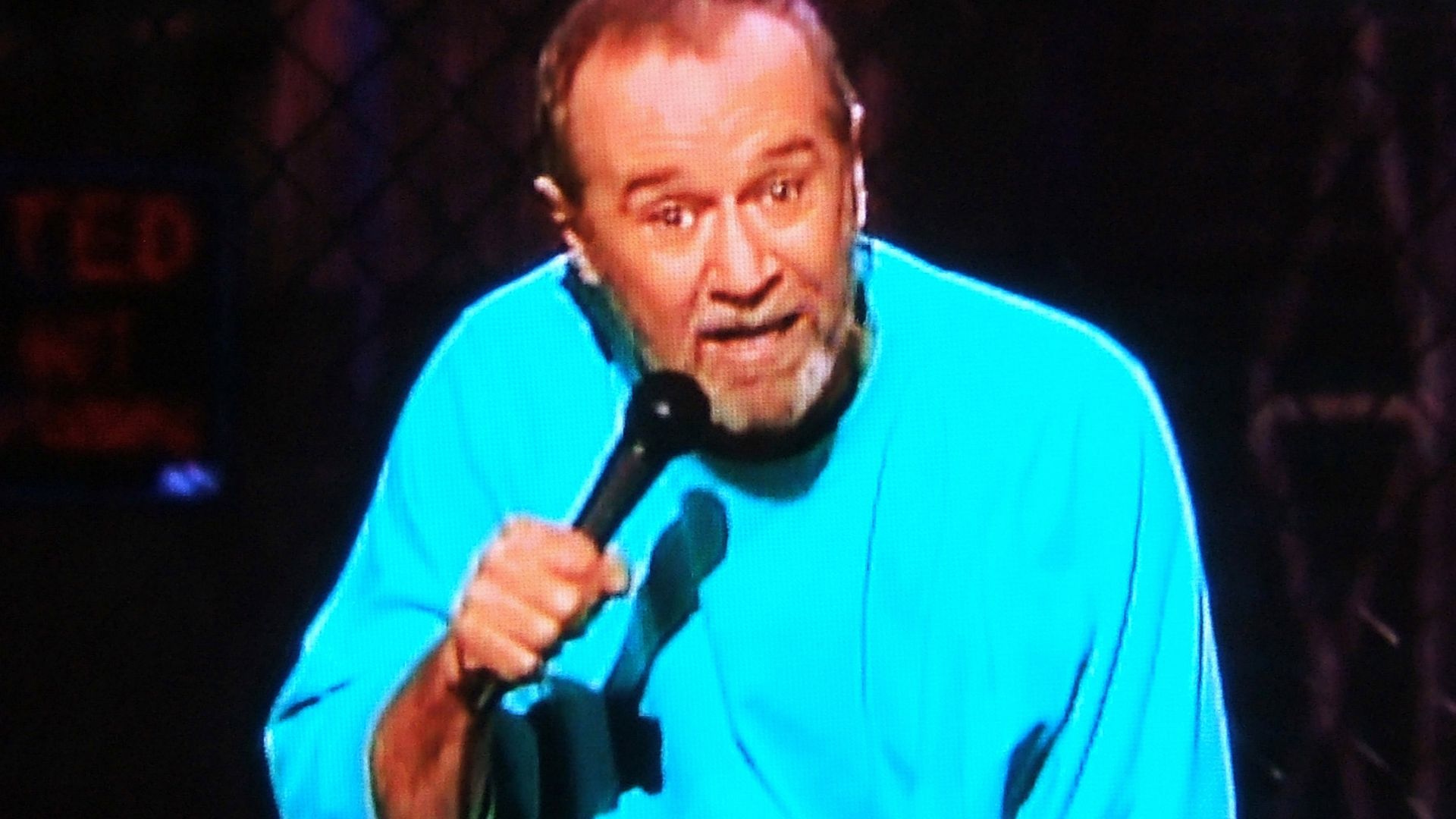

A New Kind Of Comedy

By the 1990s, Carlin wasn’t doing punchlines—he was doing philosophy with a mic. Specials like Jammin’ in New York and Back in Town turned into full-on dissections of modern life. He took on greed, politics, war, and hypocrisy. Some laughed; others squirmed. That’s exactly how he liked it.

HBO, Jammin' in New York (1992)

HBO, Jammin' in New York (1992)

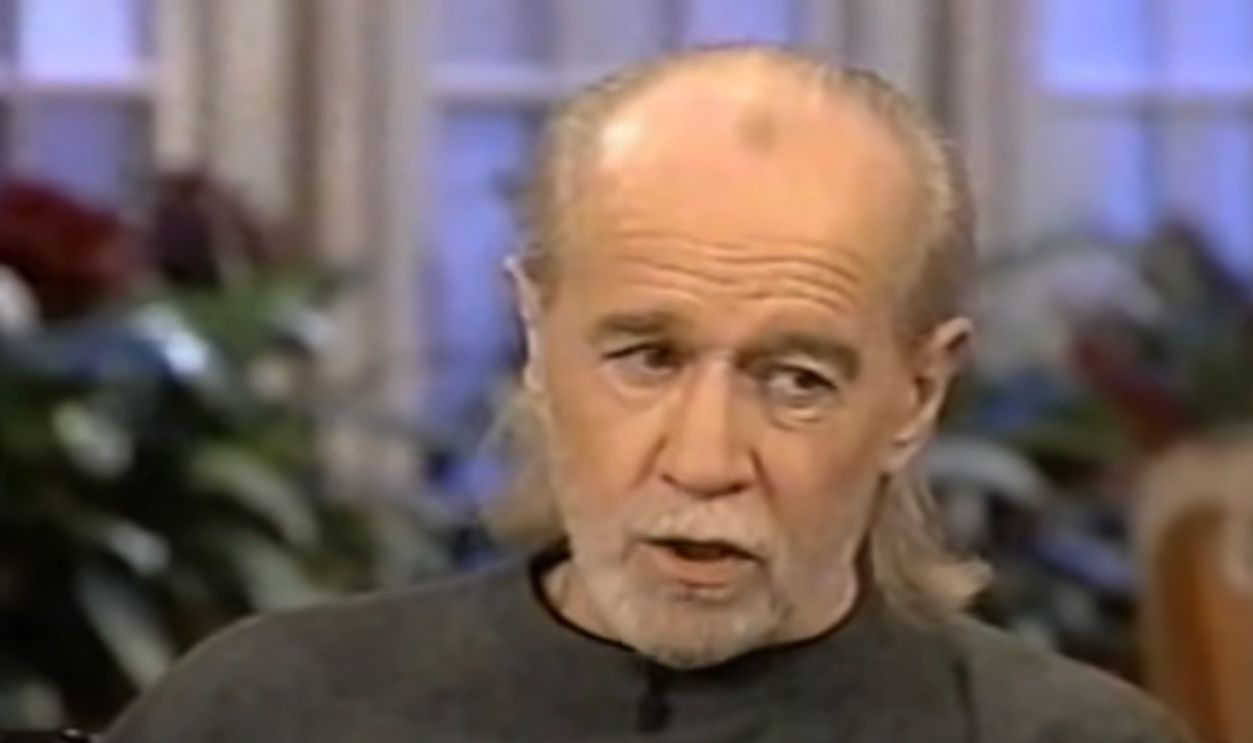

Then Came 1997

In May 1997, Brenda, his wife of 36 years, died of liver cancer. She was only 57. Carlin was gutted. He drank more, worked obsessively, and disappeared from public life for a while. Friends said the loss left him raw in a way no audience could ever see.

GEORGE CARLIN talks about MORTALITY, MyTalkShowHeroes

GEORGE CARLIN talks about MORTALITY, MyTalkShowHeroes

Picking Up The Mic Again

Eventually, Carlin went back on stage. But the warmth was gone. His first big special afterward, You Are All Diseased (1999), was sharper, darker, and far more cynical. It was like he’d stopped trying to comfort people and started trying to wake them up.

HBO, You Are All Diseased (1999)

HBO, You Are All Diseased (1999)

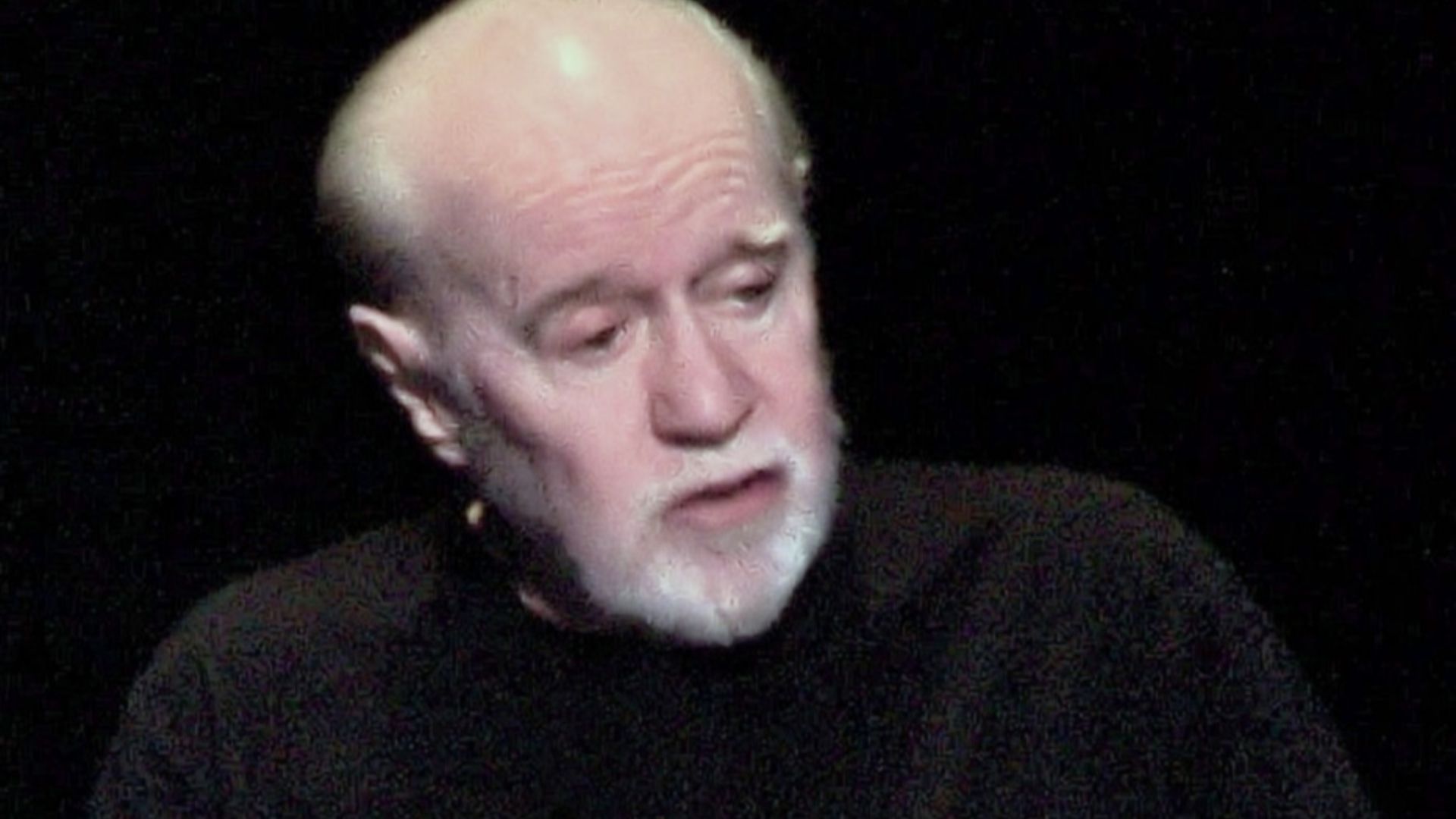

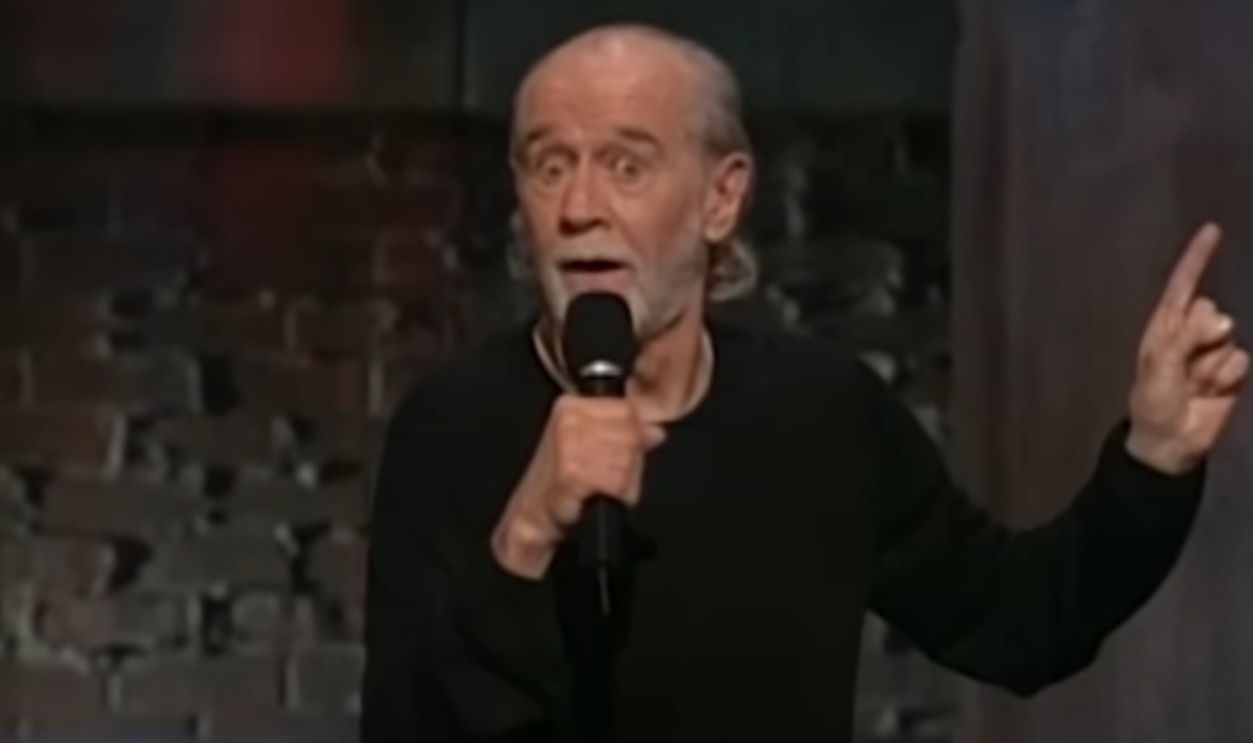

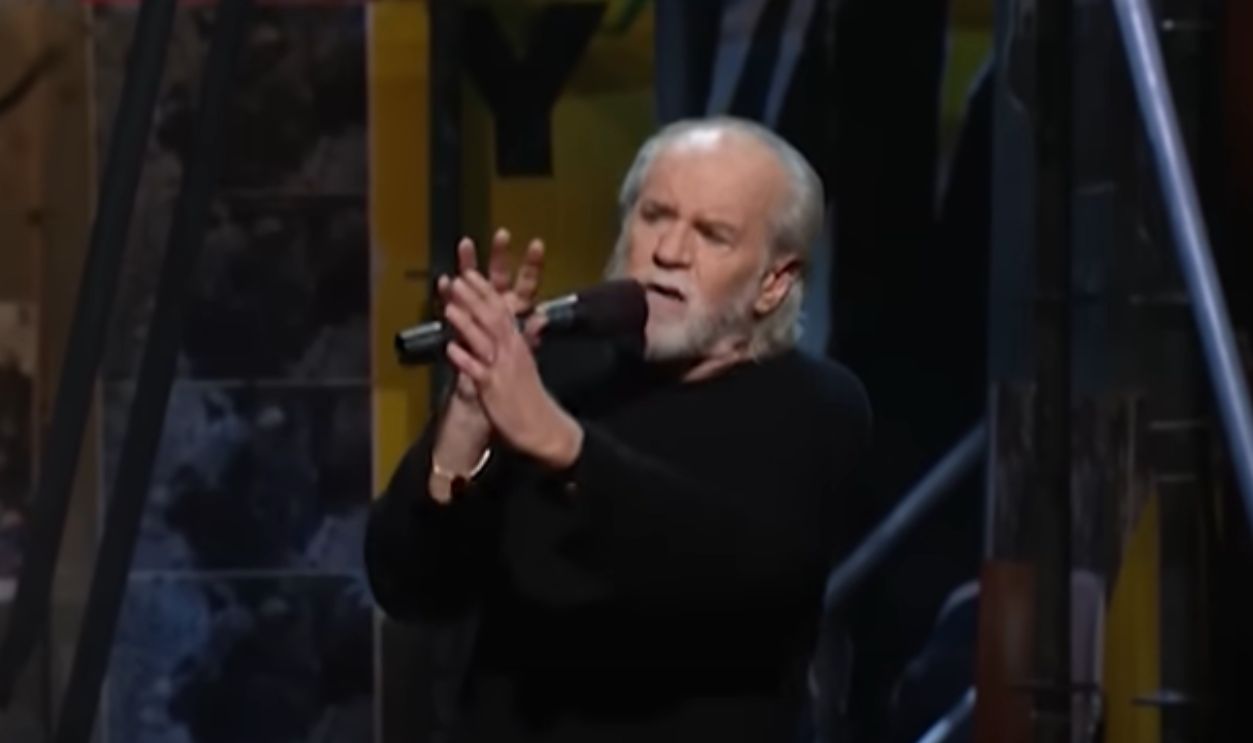

The Angry Prophet

Carlin’s later specials Complaints and Grievances, Life Is Worth Losing, It’s Bad for Ya weren’t just comedy; they were cultural X-rays. He ranted about consumerism, politics, and “the illusion of choice.” He sounded bitter, but what he really was—was heartbroken.

HBO, Complaints and Grievances ((2001)

HBO, Complaints and Grievances ((2001)

“Scratch Any Cynic...”

Carlin often said, “Scratch any cynic and you’ll find a disappointed idealist.” That line could’ve been his own biography. His anger wasn’t from hate; it was from watching a world he once believed in fall apart.

Little David Records, Wikimedia Commons

Little David Records, Wikimedia Commons

The Body Starts To Rebel

Years of touring, stress, and hard living caught up to him. Carlin had multiple heart attacks and several health scares. Still, he refused to slow down. He told 60 Minutes: “I think of death as part of life’s joke. I just hope it’s got a good punchline.

A Softer Chapter

Later in life, Carlin found new companionship with comedy writer Sally WadeKelly, who called herself his “spouse equivalent.” His daughter said it was the first time she’d seen him truly happy again. Sally later said being with Carlin revealed a softer side few people ever saw.

Sally Wade - The Geore Carlin Letters - Part 1, Connie Martinsona

Sally Wade - The Geore Carlin Letters - Part 1, Connie Martinsona

The Final Act

Carlin died in 2008 of heart failure at 71—just months after releasing . In that special, he closed with one of his most quoted lines: “It’s called the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe it.”

Alex Lozupone, Wikimedia Commons

Alex Lozupone, Wikimedia Commons

Still Speaking To Us

Years later, his words are everywhere—from memes to protest signs. Younger comics call him a blueprint for fearless honesty. He didn’t just make jokes; he made people look in the mirror.

Kevin Armstrong, Wikimedia Commons

Kevin Armstrong, Wikimedia Commons

The Lie He Told Himself

Carlin always claimed he didn’t care anymore. But he did. That was the lie he told himself, maybe the only one he ever told. Beneath the sarcasm was a man who still wanted the world to do better, even if he’d stopped believing it could. He cared deeply—about people, the planet, and the truth.

Tony Fischer, Wikimedia Commons

Tony Fischer, Wikimedia Commons

You Might Also Like:

Celebrities Who Have Actually Saved People’s Lives In Real Life