When Cameras Refuse to Blink

Sometimes, the most unforgettable movie moments aren’t built on clever editing—but on the pure nerve of refusing to cut. A single take can feel like a heartbeat stretched to infinity, pulling audiences through chaos, beauty, or unbearable suspense without a single break. These “oners” have shaped cinema history, turning technical wizardry into emotional alchemy. Here are ten that didn’t just impress—they defined the movies they came from.

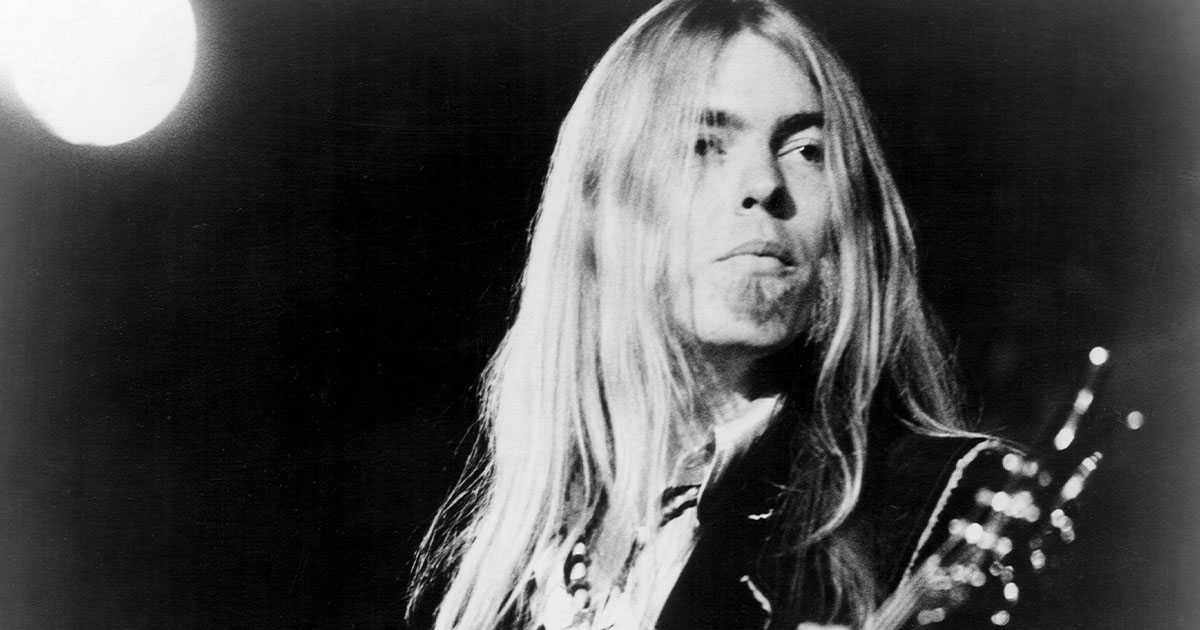

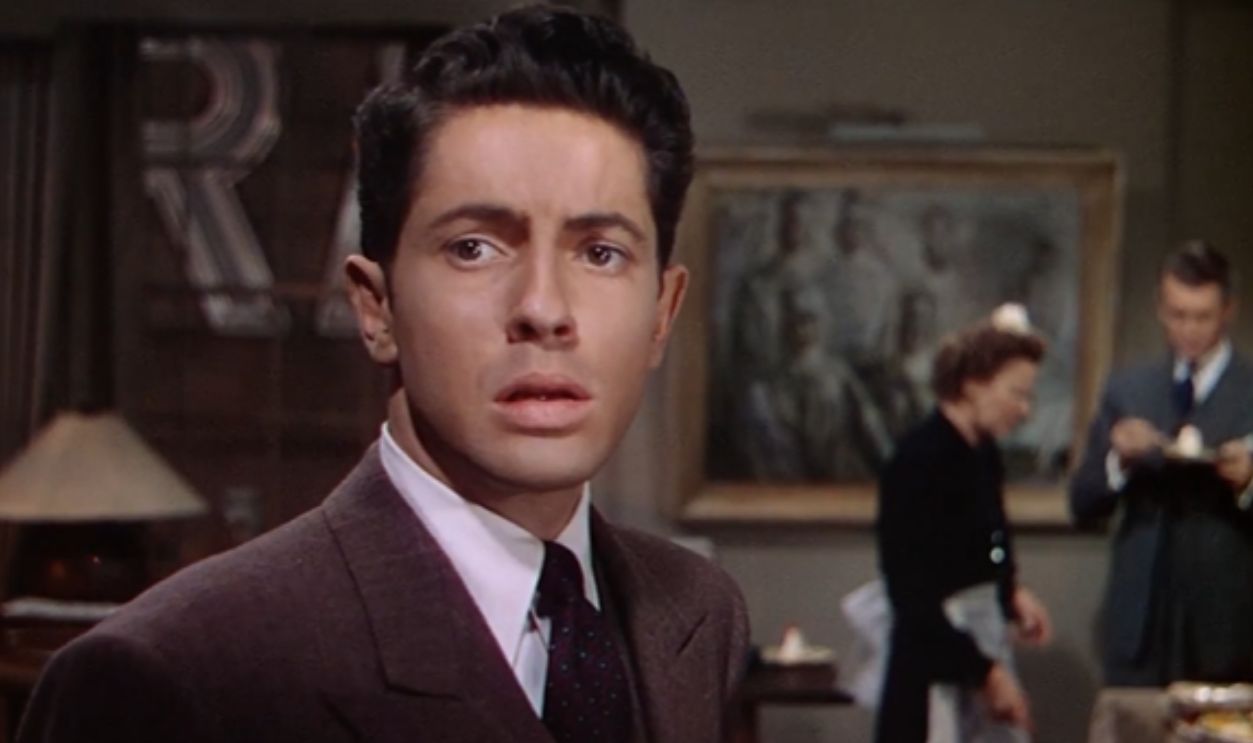

Rope (1948)

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope feels like watching a magician work without a net. Adapted from a stage play, it traps the viewer inside a Manhattan apartment with two arrogant killers who host a dinner party while their victim’s body sits in a chest nearby. Hitchcock’s camera prowls through the confined space, turning the entire film into a suffocating psychological experiment that blurs the line between audience and accomplice.

Screenshot from Rope, Warner Bros.

Screenshot from Rope, Warner Bros.

The Dinner Party That Wouldn’t End

Using long takes disguised by clever camera pans and cut-hiding close-ups, Hitchcock made the 89-minute movie look like just a handful of continuous shots. The result is a masterpiece of unease—each glide of the camera builds dread, daring you to look away but never giving you the chance. It’s theatre, cinema, and voyeurism all in one continuous breath.

Screenshot from Rope, Warner Bros.

Screenshot from Rope, Warner Bros.

Touch of Evil (1958)

Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil opens with a bang—literally. The noir classic follows an investigation in a corrupt border town, and its world-weary style would influence generations of filmmakers to come. Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, and Welles himself orbit a story drenched in paranoia and moral decay.

Screenshot from Touch of Evil, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from Touch of Evil, Universal Pictures

The Bomb That Set the Standard

Before dialogue even begins, Welles unleashes one of the most studied tracking shots in history: a three-and-a-half-minute crane sequence that follows a car wired with explosives. The camera floats, glides, and taunts as the ticking device drifts toward its fate. It’s not just tension—it’s dread rendered in motion, and nearly seven decades later, it’s still the benchmark for cinematic suspense.

Screenshot from Touch of Evil, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from Touch of Evil, Universal Pictures

I Am Cuba (1964)

Mikhail Kalatozov’s I Am Cuba is a political poem disguised as a film. Forgotten for decades before being championed by Martin Scorsese, the Soviet-Cuban production unfolds as a series of vignettes about life, revolution, and despair in pre-Castro Cuba. The black-and-white cinematography glows like liquid silver, its imagery both surreal and searing.

Screenshot from I Am Cuba, Mosfilm

Screenshot from I Am Cuba, Mosfilm

The Funeral That Defied Gravity

Its most legendary moment sees the camera start at street level during a funeral procession, then rise four stories into the air, float through a window, and glide over a city square—all in one take. It’s an act of cinematic sorcery that makes you wonder whether the camera itself is mourning, drifting between the living and the not. It’s so audacious, it feels less filmed than conjured.

Screenshot from I Am Cuba, Mosfilm

Screenshot from I Am Cuba, Mosfilm

Goodfellas (1990)

Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas redefined gangster movies by mixing swagger with sharp realism. Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill narrates his rise and fall in the mob with a charm that’s both seductive and chilling. Every frame moves to the beat of danger and glamour dancing cheek to cheek.

Screenshot from Goodfellas, Warner Bros.

Screenshot from Goodfellas, Warner Bros.

The Copacabana Seduction

When Henry leads Karen through the back corridors of the Copacabana nightclub, the camera follows in a single hypnotic take. They weave past cooks, waiters, and backdoors until the lights bloom onstage. The shot perfectly mirrors Henry’s world—effortless on the surface, but built on a maze of shortcuts, secrets, and deals with the devil.

Screenshot from Goodfellas, Warner Bros.

Screenshot from Goodfellas, Warner Bros.

The Player (1992)

Robert Altman’s The Player is Hollywood eating itself alive—and loving it. A satire of the studio system starring Tim Robbins as a manipulative executive, it’s filled with cameos, cynicism, and the kind of dialogue that only comes from insiders sharpening knives behind smiles.

Screenshot from The Player, Fine Line Features

Screenshot from The Player, Fine Line Features

The Longest Laugh in Hollywood

Altman kicks off his comeback with an eight-minute opening shot that circles a movie lot, eavesdropping on a dozen conversations at once. Studio gossip, scripts, and even a cheeky reference to Touch of Evil swirl together. It’s a self-aware wink at Hollywood’s obsession with its own myths—a reminder that no one lampoons show business better than the people trapped inside it.

Screenshot from The Player, Fine Line Features

Screenshot from The Player, Fine Line Features

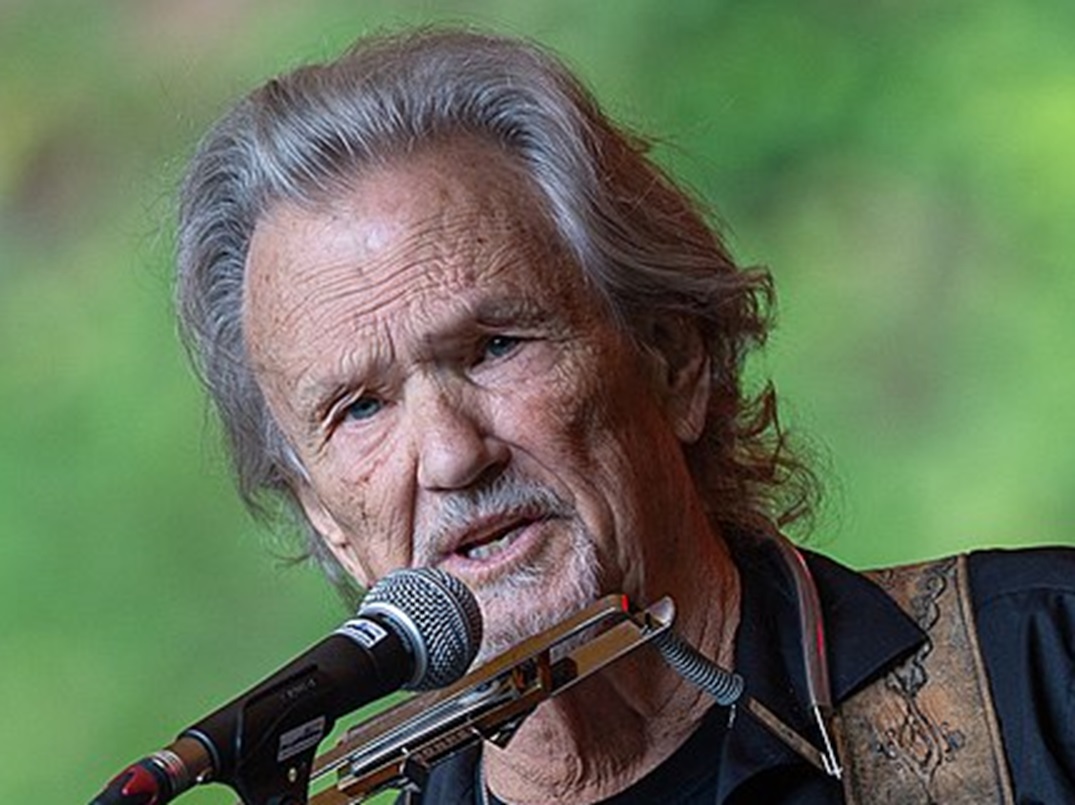

Hard Boiled (1992)

John Woo’s Hard Boiled is pure action poetry, where bullets become brushstrokes and Chow Yun-fat’s detective Tequila turns chaos into choreography. It’s loud, explosive, and deliriously over-the-top, but beneath the gunfire lies a filmmaker at the peak of his precision.

Screenshot from Hard Boiled, Miramax

Screenshot from Hard Boiled, Miramax

The Hospital Inferno

Woo’s legendary one-take gunfight unfolds in a maternity ward—a five-minute masterclass in mayhem. As the camera glides through corridors and explosions, the carnage feels both impossible and intimate. Between takes, crew members reportedly reset props and explosives during a brief elevator pause. By the time the smoke clears, you’ve witnessed action cinema at its most ferociously elegant.

Screenshot from Hard Boiled, Golden Princess Film Production

Screenshot from Hard Boiled, Golden Princess Film Production

Russian Ark (2002)

Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark is less a movie than a time machine. Set inside the Winter Palace, it follows a ghostly narrator drifting through centuries of Russian history. Shot entirely on location with a cast of over 2,000 extras, it transforms the museum into a living, breathing organism of art and memory.

Screenshot from Russian Ark, Wellspring Media

Screenshot from Russian Ark, Wellspring Media

The Take That Never Cut

The film is exactly one unbroken 87-minute take—no hidden edits, no tricks. The Steadicam glides through grand halls, waltzes across a ballroom, and converses with czars and courtiers in a feat that borders on the supernatural. It’s filmmaking as endurance art, proving that patience, not editing, can make time itself cinematic.

Screenshot from Russian Ark, Wellspring Media

Screenshot from Russian Ark, Wellspring Media

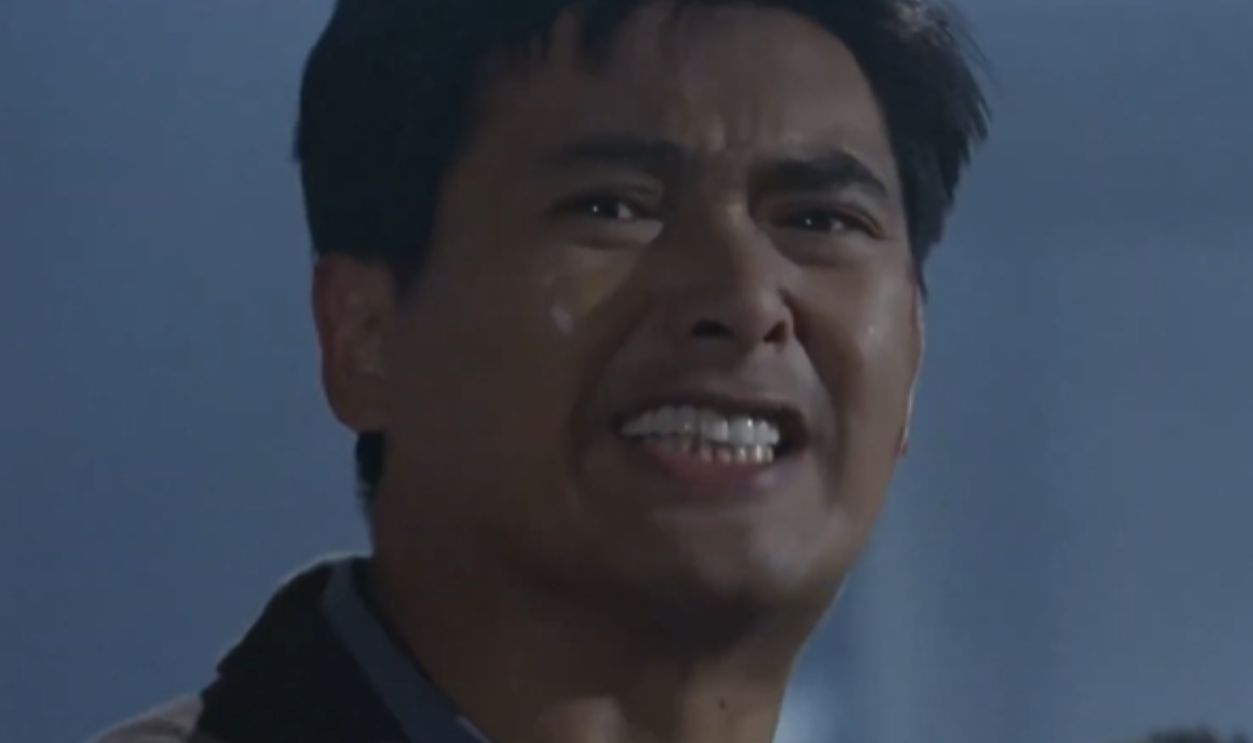

Oldboy (2003)

Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy remains one of South Korea’s most visceral achievements—a revenge story so twisted it feels mythic. Choi Min-sik’s Oh Dae-su claws his way through fifteen years of imprisonment and psychological torment to uncover who destroyed his life, and why.

Screenshot from Oldboy, CJ ENM

Screenshot from Oldboy, CJ ENM

The Hammer Ballet

When Dae-su faces a hallway full of goons armed with nothing but a hammer, the ensuing one-take fight scene is brutal minimalism at its best. The camera slides sideways like a caged spectator as Dae-su brawls through exhaustion, his pain becoming ours. The sequence inspired countless imitators—from Daredevil to Extraction—but none captured its raw, unglamorous agony.

Screenshot from Oldboy, CJ ENM

Screenshot from Oldboy, CJ ENM

Children of Men (2006)

Alfonso Cuarón’s dystopian thriller Children of Men imagines a world where humanity can no longer reproduce, and hope itself feels extinct. Clive Owen’s everyman hero carries a fragile spark of future life through a crumbling society, guided by Cuarón’s relentless vision of realism and despair.

Screenshot from Children of Men, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from Children of Men, Universal Pictures

The Car Ride From The Pit

In one of several bravura oners, the camera sits inside a car as the group is ambushed on a forest road. Using a custom rig, the lens pivots between terrified faces, capturing chaos in real time. Bullets shatter glass, the camera spins, and the audience is trapped inside the panic. Cuarón turns a single scene into a microcosm of the entire film’s desperation.

Screenshot from Children of Men, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from Children of Men, Universal Pictures

Atonement (2007)

Joe Wright’s Atonement moves between romance and regret, anchored by a single lie that destroys multiple lives. James McAvoy’s Robbie and Keira Knightley’s Cecilia ache with love they can’t reclaim, and Wright’s direction soars between intimacy and tragedy.

Screenshot from Atonement, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from Atonement, Universal Pictures

The Long Walk to Doom

With time and money running short, Wright condensed the Dunkirk sequence into a five-minute tracking shot that follows Robbie across a beach littered with chaos. Horses are shot, men sing hymns, and the camera never blinks. The moment captures the futility of infighting and the heartbreak of love lost to history. It’s the kind of shot that lingers long after the credits fade—proof that sometimes, the most powerful cuts are the ones that never happen.

Screenshot from Atonement, Universal Pictures

Screenshot from Atonement, Universal Pictures

You May Also Like:

American Remakes Of Foreign Films That Got It Wrong

Every Film Fan Needs To Check These Iconic Black & White Movies Off Their List

Can You Name Every Best Picture Winner From 2004 To 2025?

Source: 1