What You Don’t Know About The Movie

Cinema history remembers Apocalypse Now as a masterpiece, but behind its unforgettable images lies a story of chaos and obsession. Unpredictable weather, personal crises, bold decisions, and extraordinary improvisation shaped the film in ways few realize.

Orson Welles’ Abandoned Vision

Decades before Apocalypse Now, Orson Welles had planned to adapt Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. His version never materialized, but Francis Ford Coppola cited Welles’ ambition as inspiration. By transposing Conrad’s tale to Vietnam, the director fulfilled a cinematic dream Welles abandoned, and turned a literary classic into one of Hollywood’s defining war epics.

Acme Newspictures, Inc., Wikimedia Commons

Acme Newspictures, Inc., Wikimedia Commons

From Six Weeks To Sixteen Months

What was supposed to be a routine six-week shoot turned into a grueling sixteen-month odyssey in the Philippines. Delays mounted as production spiraled beyond budget and schedule, leaving the cast and crew in prolonged uncertainty. This extended timeline contributed to the film’s intensity but nearly broke those working on it.

Nathalie2010, Wikimedia Commons

Nathalie2010, Wikimedia Commons

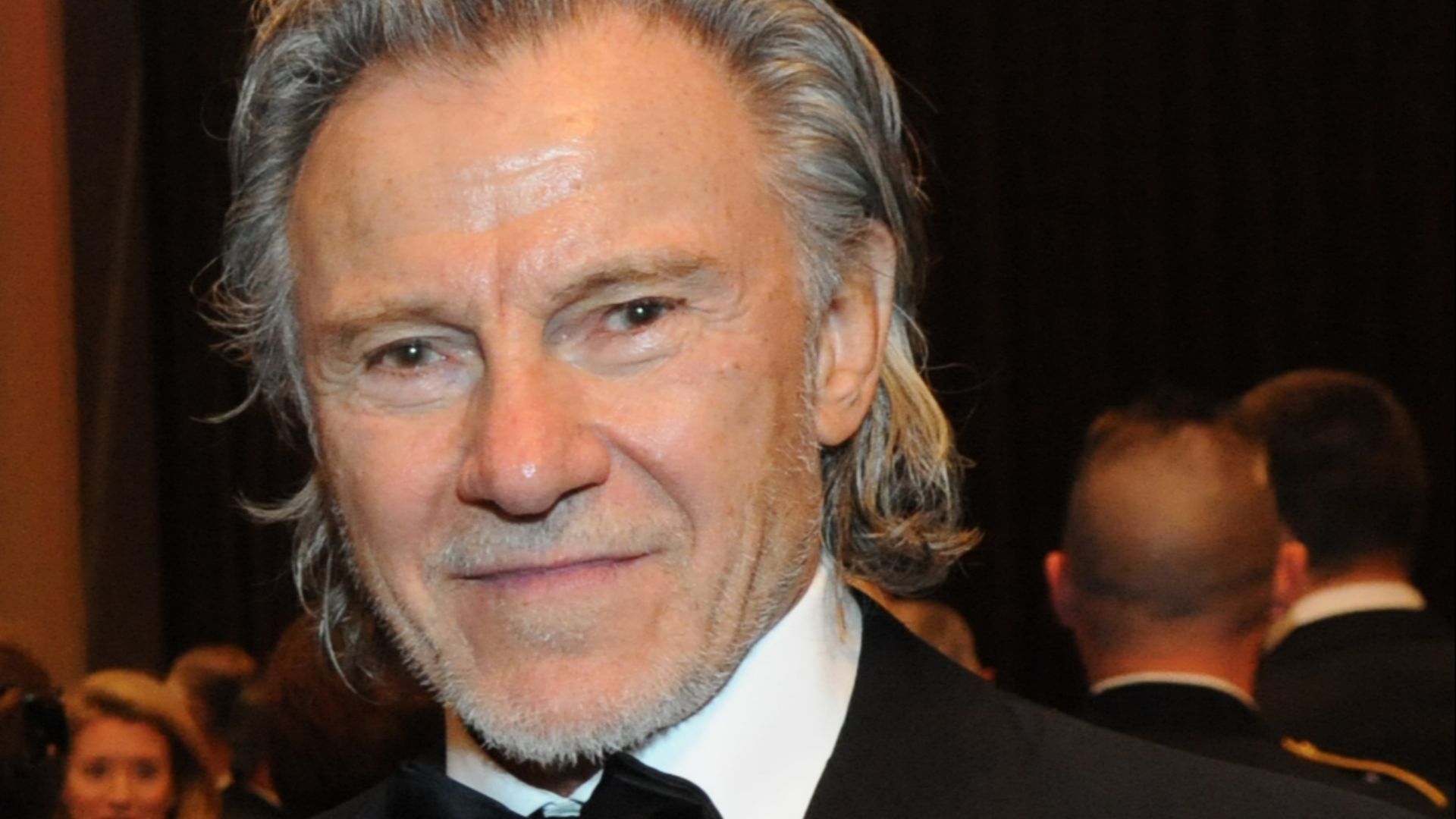

Harvey Keitel Replaced After One Week

Coppola initially cast Harvey Keitel as Captain Willard, but after a week of shooting, he decided the actor’s interpretation lacked the brooding detachment he envisioned. Martin Sheen stepped in, bringing a darker, more haunted presence that reshaped the film’s tone and gave Willard the weary intensity audiences remember today.

Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Edwin L. Wriston, Wikimedia Commons

Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Edwin L. Wriston, Wikimedia Commons

A $30 Million Gamble

In a high-stakes move, Coppola poured nearly $30 million of his personal fortune into the film. He mortgaged properties and shouldered immense financial pressure. Had the project failed commercially, the director risked personal ruin. This gamble highlighted his relentless commitment to making Apocalypse Now exactly as he envisioned.

Bernard Gotfryd, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gotfryd, Wikimedia Commons

Improvisation On The Spot

Coppola often withheld full script pages from his cast, forcing them to inhabit their roles with improvisation. This approach led to spontaneous, unpredictable moments that carried a raw edge. Some of the film’s most memorable lines and scenes emerged this way, and shed light on the unpredictable energy of war and psychological disintegration.

Gerald Geronimo, Wikimedia Commons

Gerald Geronimo, Wikimedia Commons

Redefining Military Characters On Screen

Unlike earlier patriotic portrayals, Apocalypse Now depicted US military leaders as unstable, corrupt, or disturbingly detached. Robert Duvall’s carefree Colonel Kilgore and Marlon Brando’s brooding Kurtz represented extremes of absurdity and menace. This shift influenced later works like Platoon and Full Metal Jacket, and encouraged grittier, more complex portrayals of war’s human cost.

Samantha Quigley/American Forces Press Service, Wikimedia Commons

Samantha Quigley/American Forces Press Service, Wikimedia Commons

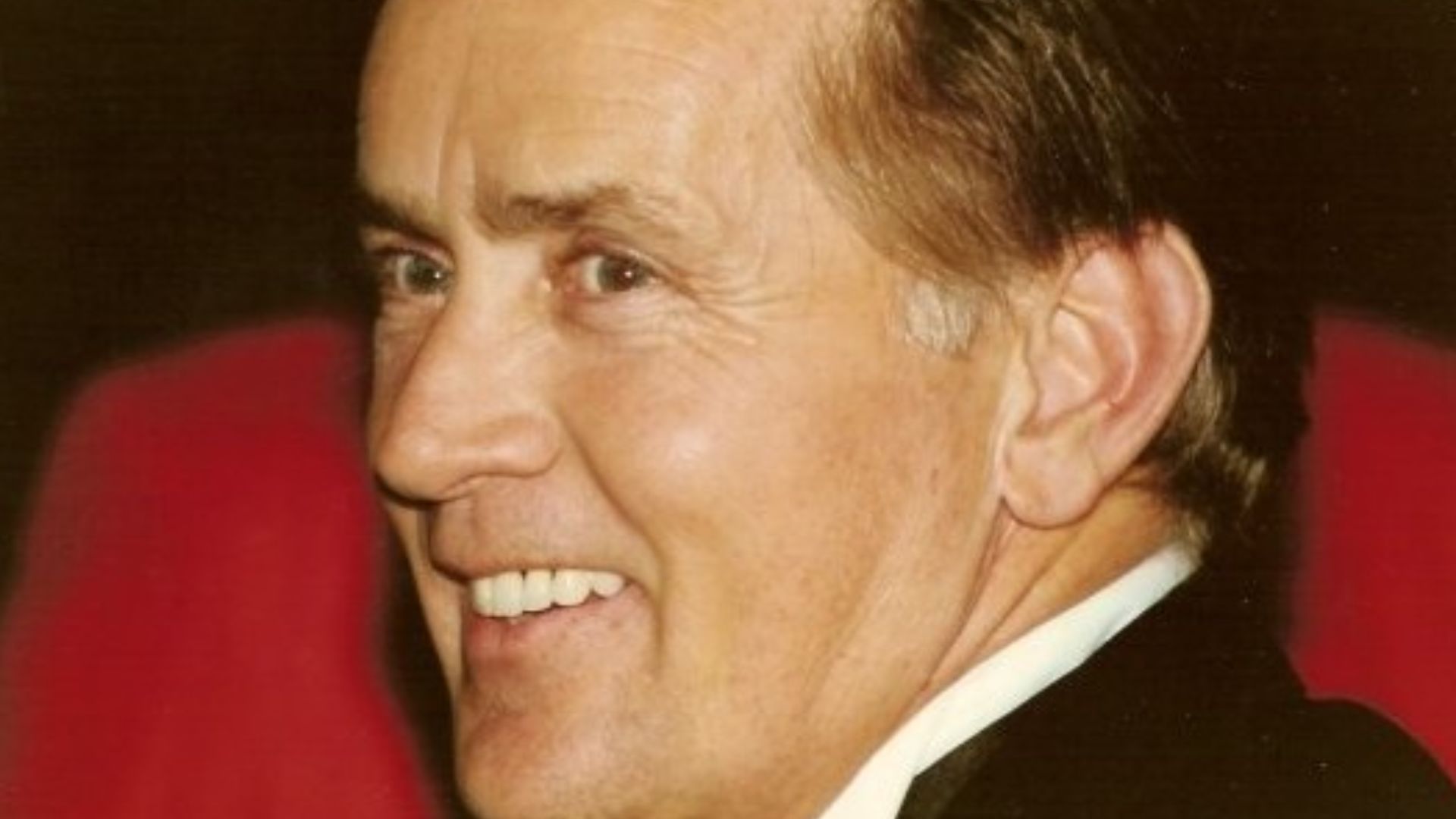

Brando’s Chaotic Arrival

When Marlon Brando finally arrived in the Philippines, he shocked Coppola by being overweight and unfamiliar with the script. The director was forced to improvise, shrouding Brando’s Kurtz in shadow and crafting dialogue on the spot. The result turned limitations into strengths that created one of cinema’s most enigmatic villains.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A Real Breakdown On Camera

The opening hotel-room scene, where Captain Willard spirals into despair, highlighted Sheen’s genuine breakdown. Intoxicated and emotionally unstable, he smashed a mirror and injured his hand. Coppola kept filming, turning a dangerous moment into raw authenticity. The unscripted collapse mirrored the character’s torment and set the psychological tone for the film.

Super Festivals , Wikimedia Commons

Super Festivals , Wikimedia Commons

Brando’s Shaved Head Transformation

Brando’s impulsive decision reshaped Colonel Kurtz forever: he shaved his head. This stark transformation gave the character an austere, menacing presence. The look amplified Kurtz’s aura of madness and authority. This creative choice helped define one of cinema’s most haunting figures.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

“This Movie Is Vietnam”

Coppola famously told his cast and crew, “This movie is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam”. He intended to capture not only the conflict’s brutality but also the madness surrounding it. That philosophy pushed the production into dangerous territory that mirrored the very chaos the film sought to portray.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

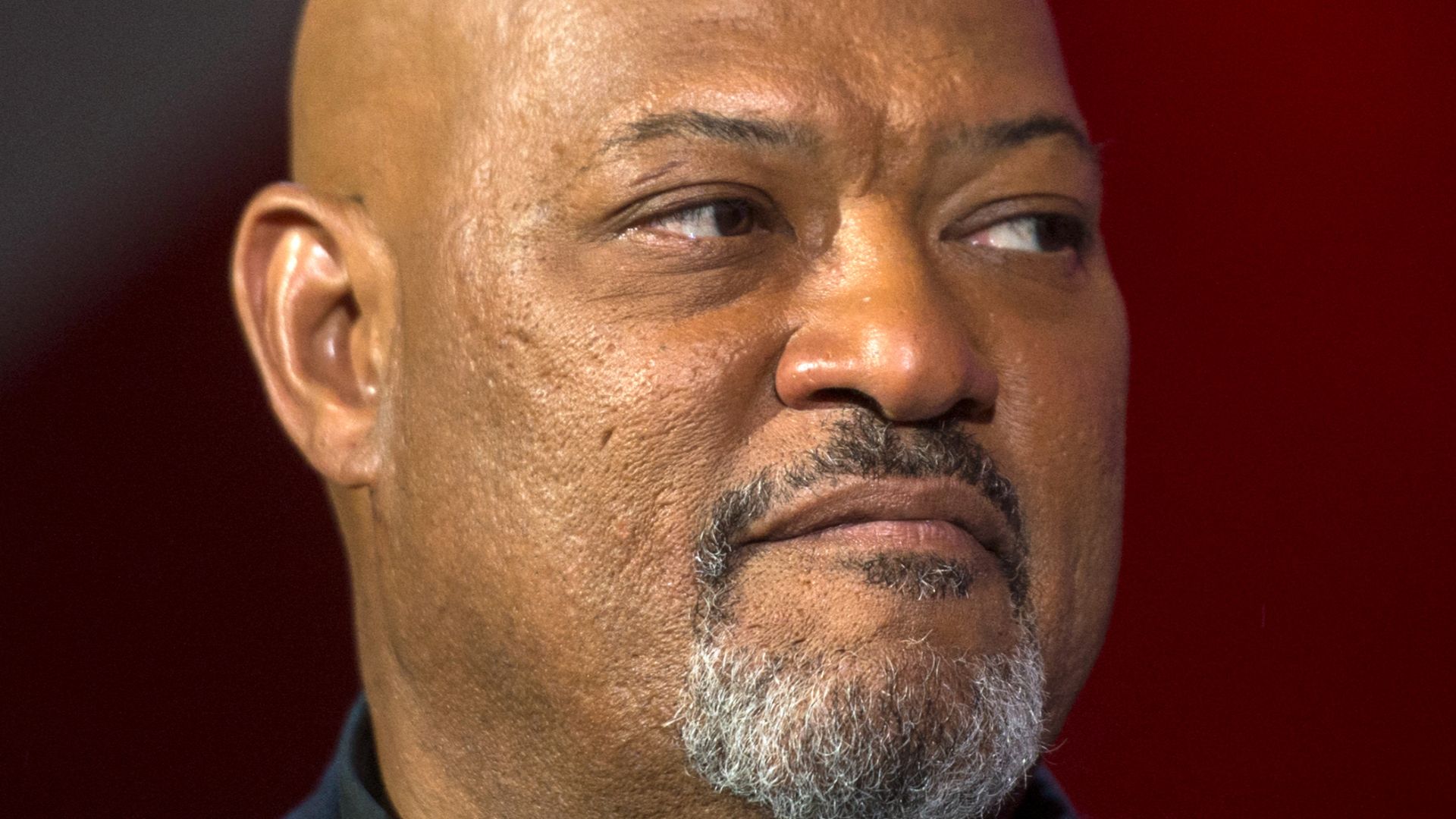

Laurence Fishburne Lied About His Age

At just fourteen, Laurence Fishburne fabricated his age to secure the role of Clean, a young soldier caught in the chaos of Vietnam. The innocence he naturally brought to the character made his fate all the more devastating. Decades later, Fishburne credited the experience with launching his long and celebrated career.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from Washington D.C, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from Washington D.C, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Helicopters Recalled To Battle

The Philippine military provided helicopters and pilots, but their cooperation was unpredictable. Midway through filming scenes, helicopters were often recalled to fight communist insurgents. This constant disruption forced sudden rewrites and delays, adding real-world volatility to an already unstable production.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

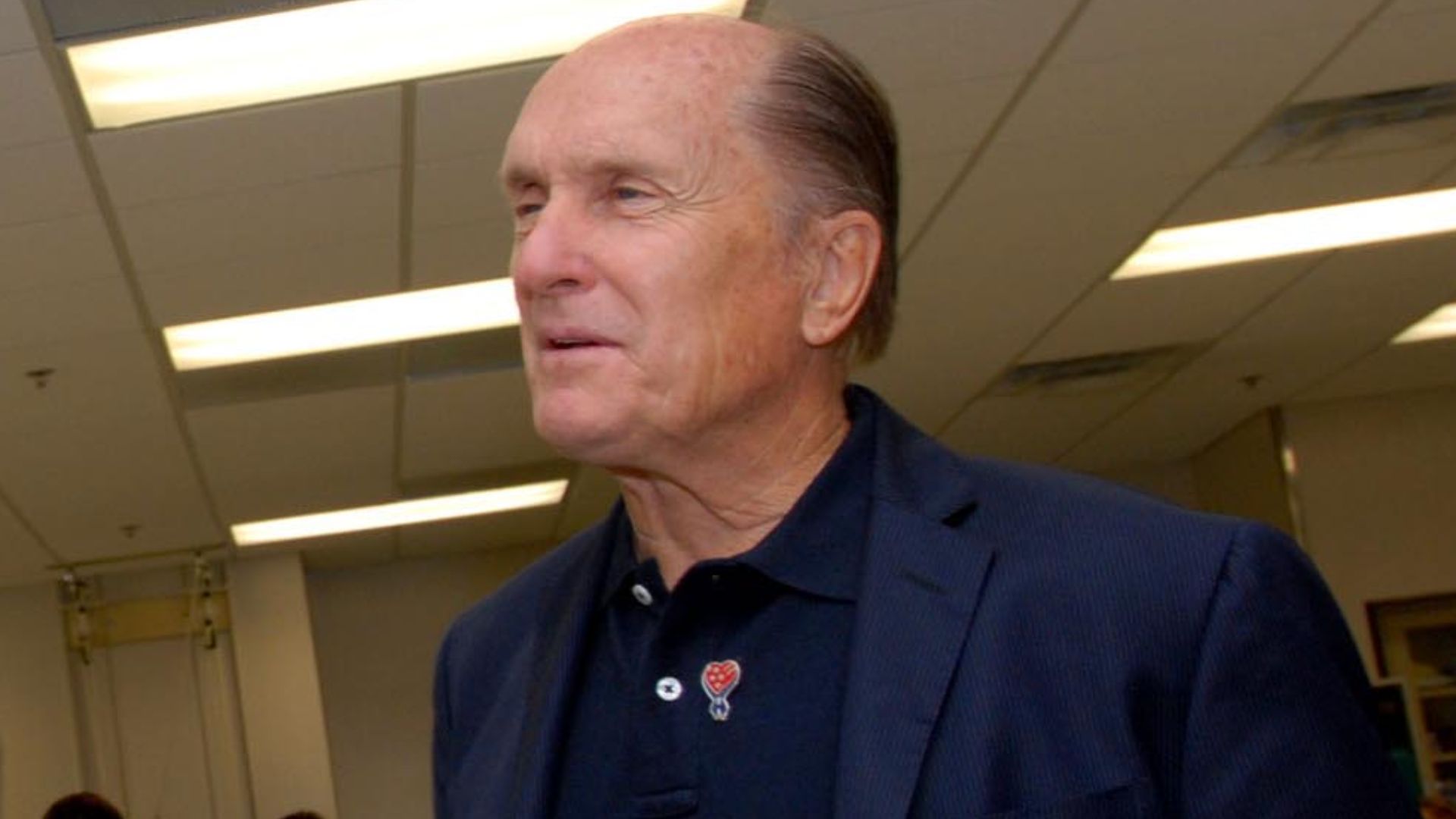

Martin Sheen’s Heart Attack On Set

During filming, Sheen collapsed from a serious heart attack at just thirty-six years old. Coppola, determined to continue, quietly used Sheen’s brother Joe as a stand-in for certain shots. The secrecy surrounding Sheen’s condition highlighted both the film’s demanding environment and the director’s desperation to keep the project alive.

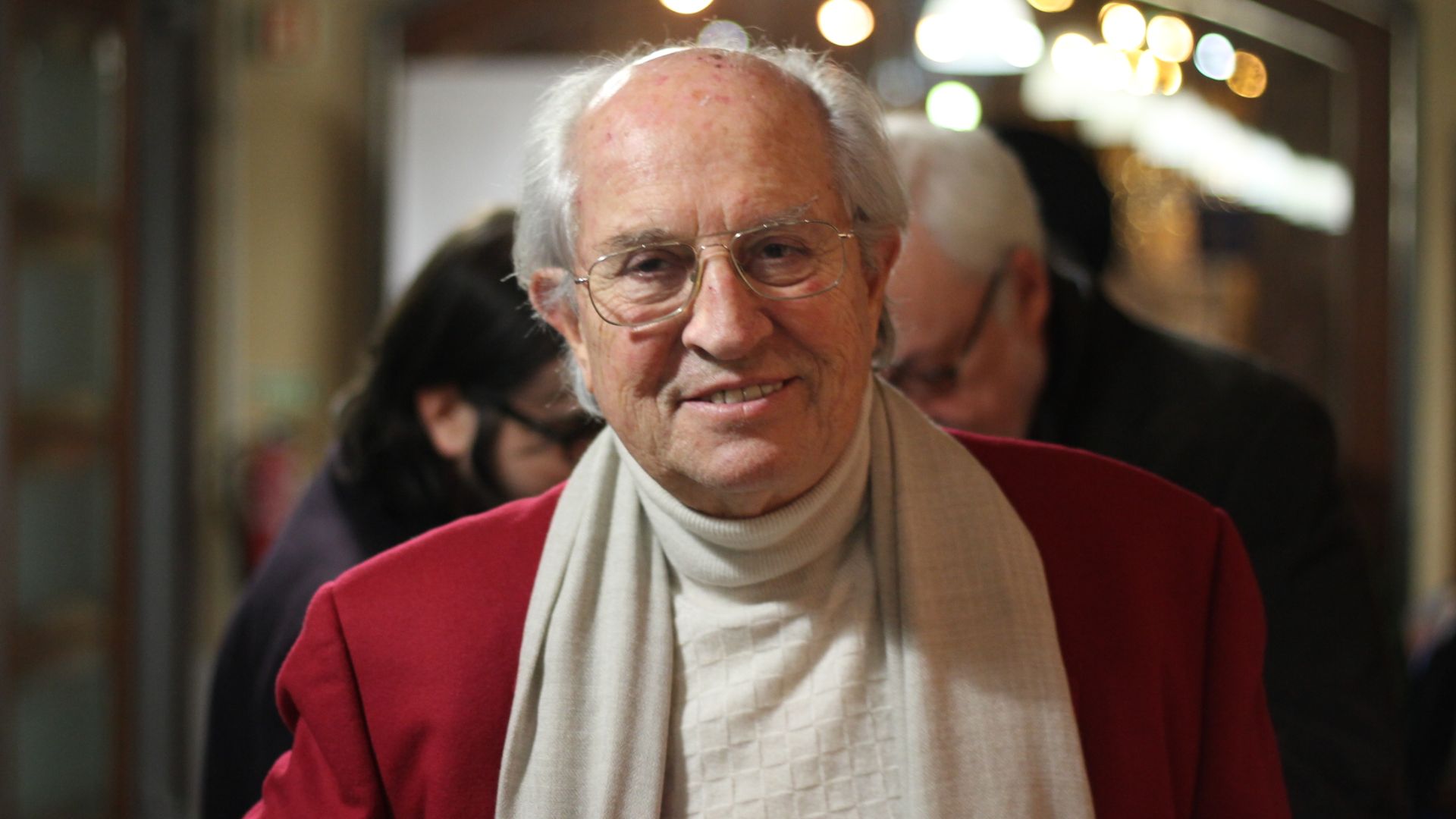

Georges Biard, Wikimedia Commons

Georges Biard, Wikimedia Commons

Typhoon Destruction And Rebuilt Sets

Nature itself fought against Apocalypse Now. A devastating typhoon tore through the Philippines, leveling entire sets and halting production for weeks. Coppola refused to abandon his vision and chose to rebuild from scratch. The setback pushed filming further into chaos and cemented the movie’s reputation as one of Hollywood’s most troubled projects.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Kilgore’s Real-Life Inspiration

Robert Duvall’s unforgettable Colonel Kilgore, famous for loving surfing more than combat, was partly inspired by a real Vietnam War officer. This eccentric model brought authenticity to the character’s bizarre detachment. Kilgore’s obsession made him both absurd and terrifying by representing the strange blend of bravado and madness that defined Coppola’s vision of war.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Voice-Over Written After Filming

Much of Captain Willard’s reflective narration was not scripted during production but crafted afterward in post-production. This decision added a noir-like quality and allowed audiences to enter his troubled psyche. The contemplative monologues deepened the narrative and provided philosophical weight that helped bridge the film’s surreal visuals with its existential themes.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

A Director On The Brink

The strain of endless delays, financial peril, and creative obstacles pushed Coppola to his breaking point. He later admitted to feeling paranoid and depressed while directing. His personal struggle mirrored the story’s descent into madness, blurring lines between life and art in unsettling, unforgettable ways.

Dennis Hopper’s Drug-Fueled Performance

Dennis Hopper delivered the reckless, unpredictable energy Coppola wanted, but his heavy drug use on set made filming nearly impossible. Often incoherent and difficult to direct, Hopper nevertheless gave a performance brimming with manic intensity. His chaotic presence perfectly reflected the madness of the story and became iconic in the finished film.

Pioneering Surround Sound Design

Apocalypse Now became one of the first films to fully embrace surround sound technology. The helicopter attack sequence immersed audiences with roaring rotors circling the theater and bullets whizzing. This innovation transformed cinematic soundscapes and set a new benchmark for how war films and action epics could overwhelm the senses.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Vittorio Storaro’s Dreamlike Jungle

Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro used natural light and experimental filters to craft the movie’s surreal atmosphere. Sunlight filtered through smoke and foliage, giving the jungle a hallucinatory glow. His visual artistry elevated Apocalypse Now beyond a war film and transformed it into a haunting meditation on madness and obsession.

Ilya Mauter, Wikimedia Commons

Ilya Mauter, Wikimedia Commons

“Ride Of The Valkyries” As Opera

The legendary helicopter assault set to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” was designed like a grand opera. Coppola carefully storyboarded each beat, synchronizing music, explosions, and flight paths. The result was cinematic choreography that changed a brutal raid into one of the most iconic sequences in film history.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

The Destroyed Battle Sequence Ending

Coppola originally filmed an elaborate battle sequence at Kurtz’s compound, complete with helicopters and explosions. However, he later destroyed the footage, believing it undermined the story’s ambiguity. By choosing restraint over spectacle, Coppola left viewers with a haunting, unresolved finale that better reflected the descent into moral and psychological chaos.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

Palme D’Or For An Unfinished Film

Apocalypse Now earned the prestigious Palme d’Or at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, but the version shown was still incomplete. Coppola continued editing even after the award. The victory highlighted the film’s raw power despite its imperfections, solidifying its reputation as one of cinema’s most audacious and influential war epics.

karel leermans, Wikimedia Commons

karel leermans, Wikimedia Commons

Divided Reactions Among Veterans

American veterans of the Vietnam War responded with mixed emotions. Some praised the film for representing the chaos and confusion they remembered. Others criticized it for exaggerating the surreal and grotesque elements. This division reflected the nation’s lingering wounds and showed how art could provoke conflicting truths about collective memory.

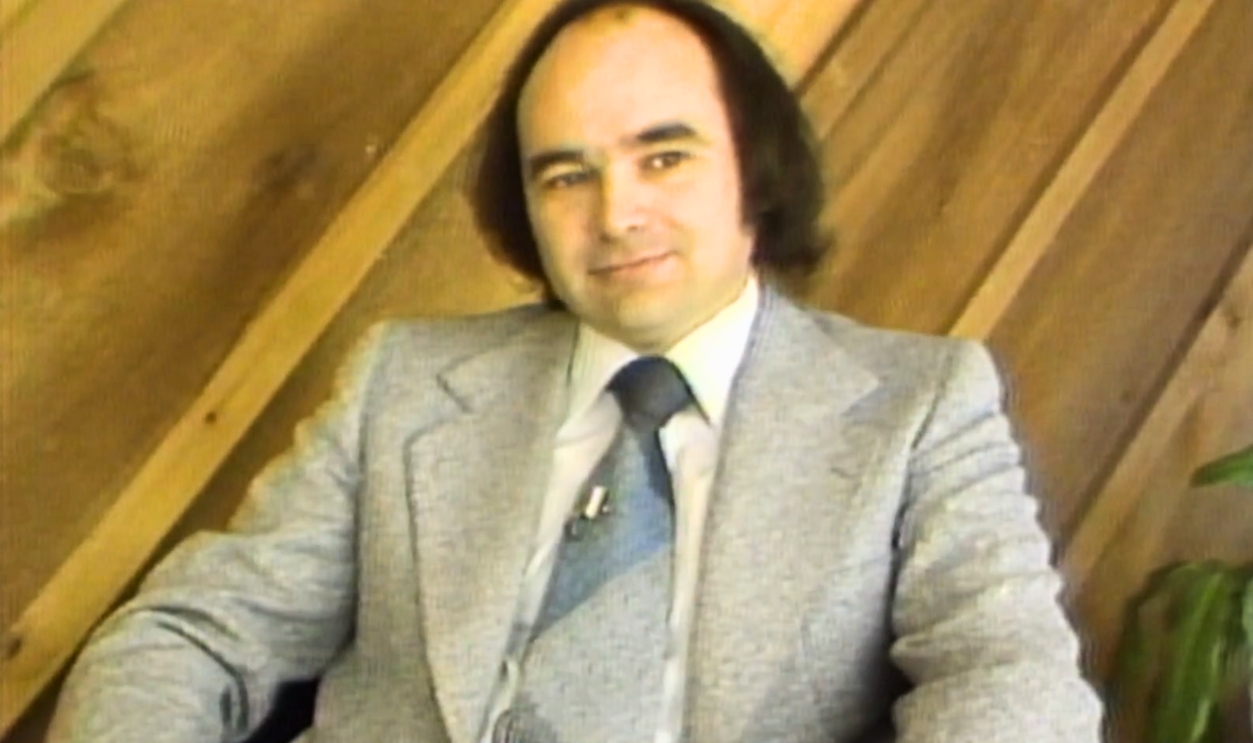

Vietnam War veteran critical of Apocalypse Now in 1979 interview with WFAA by WFAA

Vietnam War veteran critical of Apocalypse Now in 1979 interview with WFAA by WFAA

Do Lung Bridge As A Metaphor For Madness

The Do Lung Bridge sequence stands out as one of the film’s most nightmarish moments. With no commanding officer in sight, soldiers battle endlessly, rebuilding the bridge each night only to see it destroyed again. This disorienting cycle symbolized Vietnam’s futility, portraying war as chaos without leadership or purpose.

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)

United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979)