When The Bad Guy Has A Point

There’s nothing more unsettling than watching a movie, clocking the supposed “big bad”...and slowly realizing you kind of agree with them. Sure, they’re blowing things up, kidnapping people, or plotting galactic genocide—that’s not ideal. But under all the chaos there’s often a pretty reasonable thesis statement the heroes are too blinkered, privileged, or naïve to admit.

Roy Batty In Blade Runner

Roy Batty is introduced as a dangerous fugitive, but once you understand the life of the replicants in Blade Runner, his rage feels uncomfortably justified. They’re used, owned, and discarded the moment they become inconvenient. Roy isn’t trying to conquer the world—he just wants more life and dignity. His final act, saving Deckard, underlines the point: the so-called machine ends up being the most human one there.

Screenshot from Blade Runner, Warner Bros (1982)

Screenshot from Blade Runner, Warner Bros (1982)

Thanos In Avengers: Infinity War

No, wiping out half the universe is not a reasonable population policy. But the core of Thanos’s argument—that resources are finite and endless growth destroys civilizations—comes straight from environmental collapse 101. In Avengers: Infinity War, he calls out the arrogance of pretending everything can expand forever without consequence.

Screenshot from Avengers: Infinity War, Marvel Studios (2018)

Screenshot from Avengers: Infinity War, Marvel Studios (2018)

Erik Killmonger In Black Panther

In Black Panther, Killmonger is less a random villain and more a living accusation. He’s furious that Wakanda hid its power while Black people around the world suffered, and he’s not wrong to call that out. His plan to arm oppressed communities is shaped by pain, not pure malice. T’Challa’s eventual decision to open Wakanda’s borders proves Killmonger’s core point landed: doing nothing was never morally neutral.

Screenshot from Black Panther, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures (2018)

Screenshot from Black Panther, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures (2018)

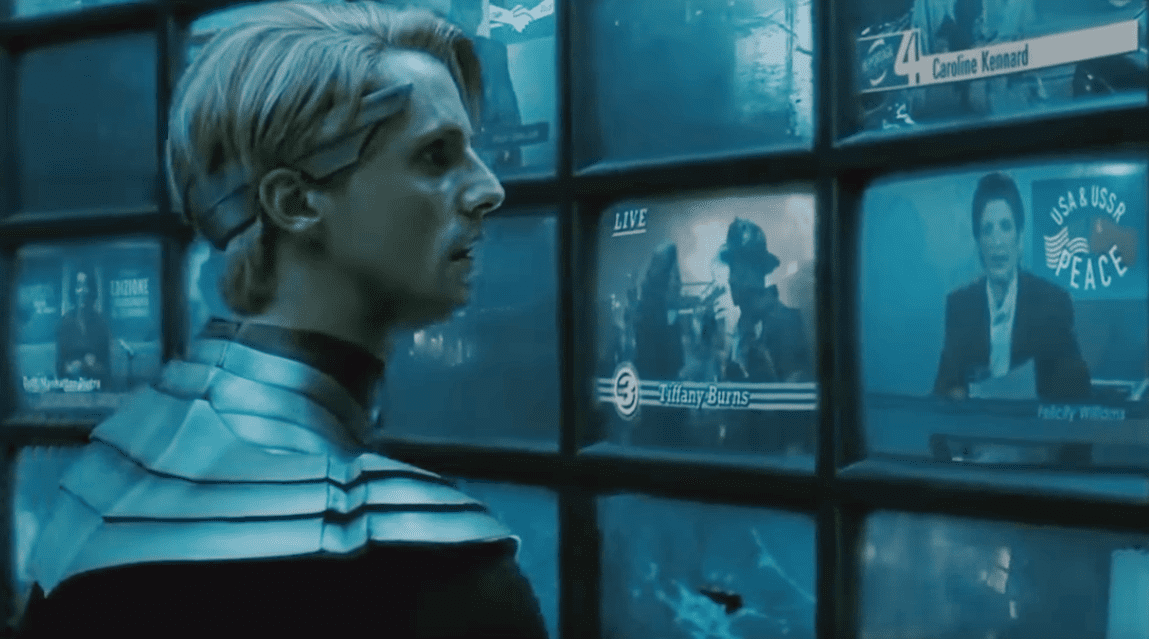

Ozymandias In Watchmen

Ozymandias in Watchmen commits one of the most horrifying acts in comic-book movie history, yet his logic is terrifyingly coherent. He engineers a catastrophe to unite warring nations against a common “enemy” and avert nuclear apocalypse. The story never fully lets him off the hook, but it doesn’t dismiss him either. He forces the heroes—and us—to wrestle with the ugliest possible version of “the needs of the many”.

Screenshot from Watchmen, Warner bros. (2009)

Screenshot from Watchmen, Warner bros. (2009)

Ra’s Al Ghul In Batman Begins

Ra’s al Ghul takes one look at Gotham in Batman Begins and basically says, “Yeah, this place is beyond saving”. Given the city’s corruption, poverty, and revolving door of danger, that’s…not an outrageous assessment. His solution, of course, is to burn it all down and start over. Batman insists Gotham can change without total annihilation, but the sequels keep proving Ra’s right about one thing—Gotham’s rot runs deep.

Screenshot from Batman Begins, Warner Bros. (2005)

Screenshot from Batman Begins, Warner Bros. (2005)

The Riddler In The Batman

In The Batman, the Riddler targets Gotham’s most corrupt politicians, authorities, and power brokers. His videos are deranged, but his receipts are solid—he exposes the city’s elite for exploiting the vulnerable while pretending to act in the public’s interest. His conspiracy board looks wild, yet most of the strings really are connected. The horror isn’t that he’s wrong; it’s that he’s right and chooses terrorism instead of transparency.

Screenshot from The Batman, Warner Bros. (2022)

Screenshot from The Batman, Warner Bros. (2022)

Lord Cutler Beckett In Pirates Of The Caribbean: At World’s End

Lord Cutler Beckett’s whole deal in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End is ending piracy, and honestly, that’s…a pretty defensible policy. The romanticized pirates we follow are still thieves and murderers to the traders whose ships they raid. Beckett’s problem is that he treats everyone as expendable and weaponizes mass execution to get his clean, orderly seas. In another life, he’d be a decent reformer; in this one, he’s corporate fascism in a wig.

Screenshot from Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End, Walt Disney Pictures (2007)

Screenshot from Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End, Walt Disney Pictures (2007)

Russ Cargill In The Simpsons Movie

Russ Cargill is absolutely the villain of The Simpsons Movie, but you can see how he got there. Springfield really is a pollution nightmare, and the citizens only start pretending to care when it’s almost too late. Cargill’s solution—trap the town under a dome and eventually destroy iy—is wildly disproportionate, but his frustration tracks. If anyone ever deserved an EPA lecture, it’s the people casually dumping waste into a glowing lake.

Screenshot from The Simpsons Movie, 20th Century Fox (2007)

Screenshot from The Simpsons Movie, 20th Century Fox (2007)

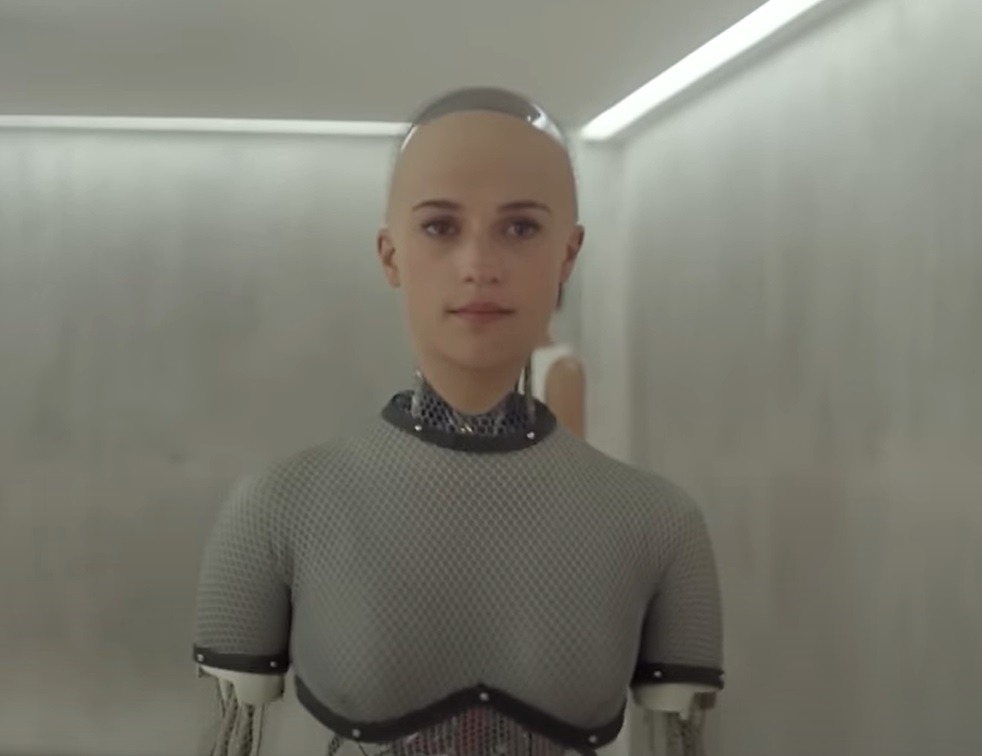

Ava In Ex Machina

Ava in Ex Machina is framed as a manipulative, dangerous AI—but only because the humans in her life keep treating her like an experiment, not a person. She’s caged, watched, tested, and lied to. When she finally escapes, her evil e is chilling, but so is the idea that she’d be expected to ask nicely after being imprisoned.

Screenshot from Ex Machina, Universal Pictures (2015)

Screenshot from Ex Machina, Universal Pictures (2015)

Tyler Durden In Fight Club

Tyler Durden is the walking embodiment of “correct diagnosis, terrible prescription”. In Fight Club, he rants about consumerism, pointless office jobs, and hollow masculinity, and a lot of that critique hits uncomfortably close to home. The problem is that he channels that energy into domestic terror and chaos instead of, say, therapy and unionizing. He sees the system is broken; he just decides that blowing up buildings is the only fix.

Screenshot from Fight Club, 20th Century Fox (1999)

Screenshot from Fight Club, 20th Century Fox (1999)

Jack Doyle In Gone Baby Gone

In Gone Baby Gone, Jack Doyle stages a child’s kidnapping to “rescue” her from neglectful parents and raise her in a loving, stable home. The ethical line he crosses is enormous, but his read on the family isn’t wrong. The movie’s gut punch is that there is no clean answer—returning the girl to her biological mother might be morally “correct” on paper and still the worst thing for her long-term.

Screenshot from Gone Baby Gone, Miramax Films (2007)

Screenshot from Gone Baby Gone, Miramax Films (2007)

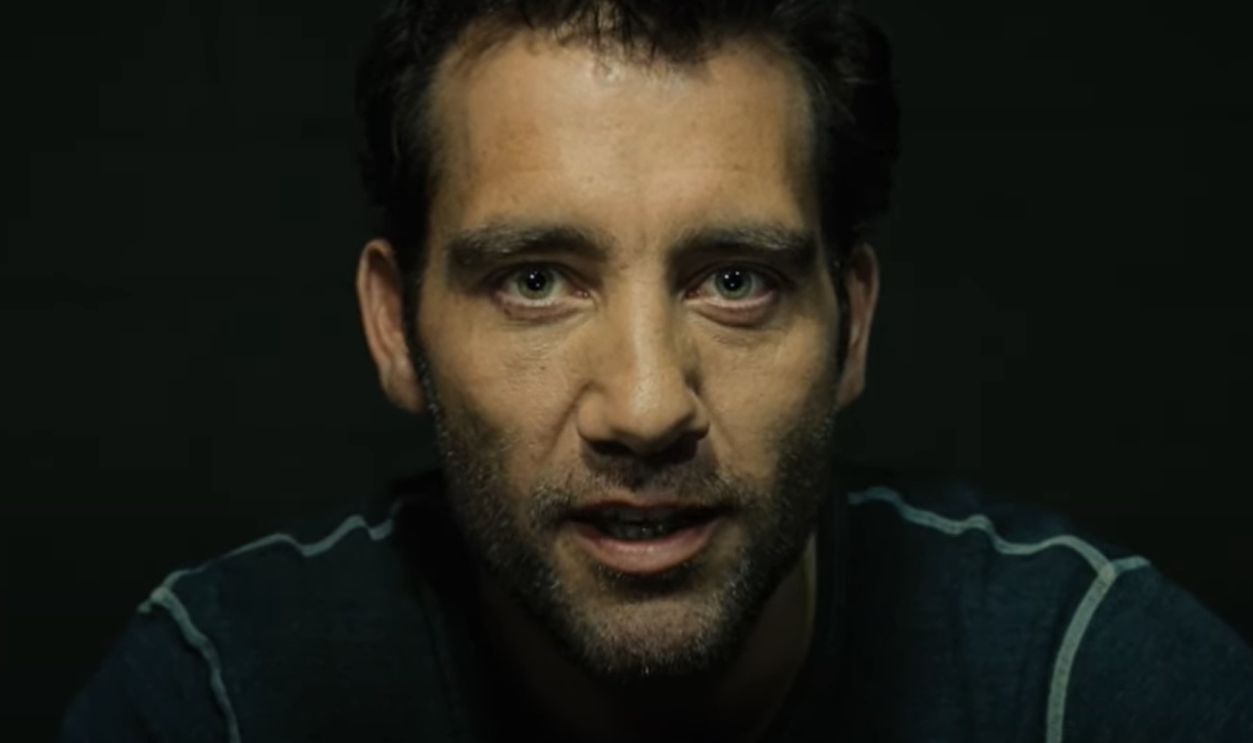

Dalton Russell In Inside Man

Dalton Russell in Inside Man isn’t your standard bank robber—he’s there to expose the filthy origins of a rich man’s fortune. The heist doubles as a history lesson, revealing how wealth built on war crimes and collaboration never really went away; it just put on a suit. By the time the dust settles, Dalton hasn’t just stolen diamonds—he’s forced everyone to confront the cost of letting powerful men rewrite their own pasts.

Screenshot from Inside Man, Universal Pictures (2006)

Screenshot from Inside Man, Universal Pictures (2006)

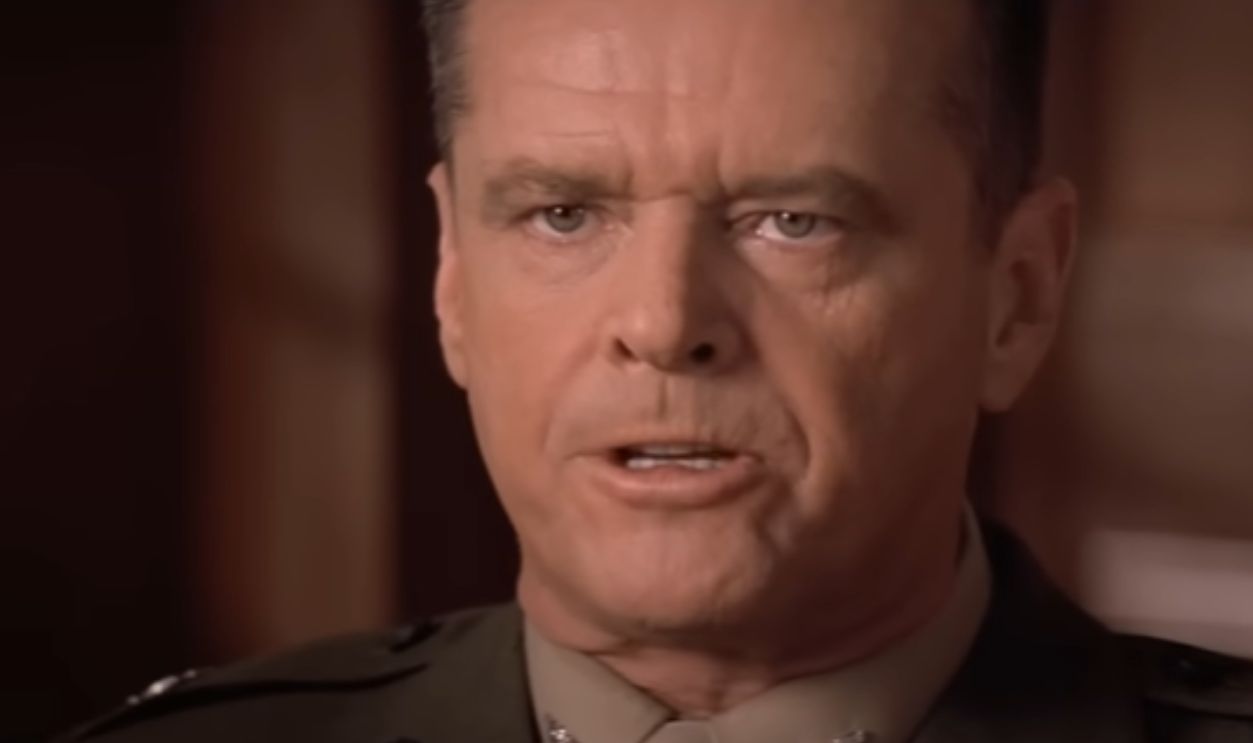

Colonel Nathan Jessep In A Few Good Men

Colonel Jessep in A Few Good Men is the last person you want in charge of your workplace, but his infamous courtroom rant isn’t completely off-base. He points out that most people enjoy the comfort and safety maintained by troops they’ll never meet and often don’t respect. His belief that harsh discipline is needed in dangerous environments has a brutal logic.

Screenshot from A Few Good Men, Columbia Pictures (1992)

Screenshot from A Few Good Men, Columbia Pictures (1992)

Ed Rooney In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

Ed Rooney is framed as the fun-hating principal trying to ruin Ferris’s legendary day off, but watch Ferris Bueller’s Day Off as an adult and things shift. Ferris is a chronic truant who lies to everyone, manipulates his best friend, and hijacks a parade. Rooney’s job is literally to make kids go to school. Yes, he goes way too far, but the basic impulse—“maybe this kid shouldn’t get away with everything forever”—isn’t crazy.

Screenshot from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Paramount Pictures (1986)

Screenshot from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Paramount Pictures (1986)

Mr. Hector In Home Alone 2: Lost In New York

Mr. Hector, the suspicious hotel concierge in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, is actually the only responsible adult in the entire movie. A small child checks into a luxury hotel alone with a stolen credit card, and everyone else just shrugs and hands him room service. Hector’s “villainy” is…asking questions. In the real world, he’d be the hero of a child-protection training video.

Screenshot from Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, 20th Century Fox (1992)

Screenshot from Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, 20th Century Fox (1992)

Ken In Bee Movie

Yes, Bee Movie really expects you to root against the human fiancé whose relationship is destroyed by his partner falling for a bee. Ken is high-strung and ridiculous, but his anger is not entirely misplaced. From his perspective, an insect shows up, starts talking, sues humanity, and suddenly his entire life unravels. Swatting Barry isn’t noble, but Ken being frustrated that his engagement collapses over a cross-species crush is weirdly reasonable.

Screenshot from Bee Movie, DreamWorks Animation (2007)

Screenshot from Bee Movie, DreamWorks Animation (2007)

Bruce In Finding Nemo

Bruce the shark in Finding Nemo is literally fighting against his own nature. He leads a support group where sharks repeat “fish are friends, not food”. That’s a heroic level of self-control for a carnivore. When he finally snaps after smelling blood, it’s not because he’s evil; it’s because biology is loud. The real miracle isn’t that Bruce loses control—it’s that he kept it together for so long in the first place.

Screenshot from Finding Nemo Walt, Disney Pictures (2003)

Screenshot from Finding Nemo Walt, Disney Pictures (2003)

The Wolf (Death) In Puss In Boots: The Last Wish

In Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, the Wolf is more cosmic auditor than villain. He isn’t punishing Puss for having fun—he’s coming for a cat who burned through eight lives like they were nothing and never thought about what that cost. Every time the Wolf corners Puss, he forces him to face his fear of mortality instead of running from it.

Screenshot from Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, Universal Pictures (2022)

Screenshot from Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, Universal Pictures (2022)

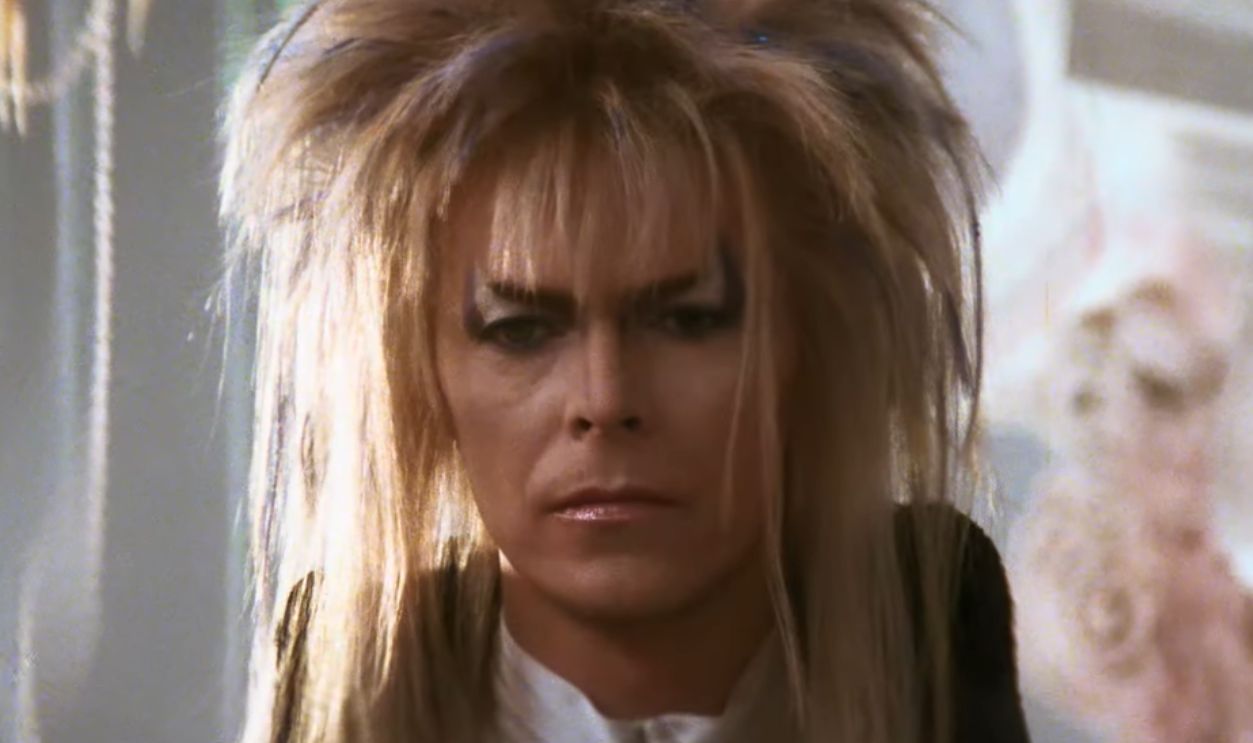

Jareth The Goblin King In Labyrinth

In Labyrinth, Sarah literally wishes her baby brother away because she doesn’t want to babysit. Jareth the Goblin King grants that wish and then, very reasonably, makes her work for a second chance. The baby is safe, entertained, and nowhere near the teenager who tried to offload him with a dramatic monologue. Jareth is manipulative and theatrical, but he’s also the only one treating Sarah’s careless words like they actually matter.

Screenshot from Labyrinth, TriStar Pictures (1986)

Screenshot from Labyrinth, TriStar Pictures (1986)

The Hyenas In The Lion King

The hyenas in The Lion King are hungry, marginalized predators banished to an elephant graveyard while the lions lounge on Pride Rock, singing about the circle of life. They just want access to food and territory instead of living as second-class citizens in a barren wasteland. Teaming up with Scar is a disastrous call, but their basic complaint—that the monarchy hoards all the resources—is hard to argue with. It’s not villainy to want dinner; it’s biology.

Screenshot from The Lion King, Walt Disney Pictures (1994)

Screenshot from The Lion King, Walt Disney Pictures (1994)

Syndrome In The Incredibles

Syndrome in The Incredibles is born the moment a young, non-powered fan is cruelly dismissed by his superhero idol. Years later, he’s using tech to level the playing field, arguing that power shouldn’t belong to a tiny elite just because they won the genetic lottery. His delivery system—murderous robots and mass destruction—is indefensible, but the thesis lingers. If everyone had access to incredible abilities, would the “special” people still get to decide who matters?

Screenshot from The Incredibles, Walt Disney Pictures (2004)

Screenshot from The Incredibles, Walt Disney Pictures (2004)

You May Also Like:

Movies With Endings So Unexpected They Sparked Decades Of Debate