The Timeless Magic Of Monochrome

There’s something magical about black & white cinema. When filmmakers lean into it, the shadows become characters, the light becomes storytelling, and suddenly, you don’t miss color at all. Here are 25 films that prove monochrome isn’t just timeless, it’s transcendent.

Citizen Kane (1941)

Orson Welles’s groundbreaking masterpiece about newspaper tycoon Charles Foster Kane isn’t just famous for “Rosebud,” it’s a visual revolution. Cinematographer Gregg Toland gave us deep focus shots where every layer of the frame is sharp, ceilings built onto sets so the camera could shoot low angles, and shadows carved with surgical precision. Every frame feels monumental, like Kane’s ego itself.

RKO Radio Pictures, Citizen Kane (1941)

RKO Radio Pictures, Citizen Kane (1941)

The Night Of The Hunter (1955)

This fairy-tale-meets-horror tale stars Robert Mitchum as a preacher with sinister motives, chasing two children through a shadowy world. Director Charles Laughton fills the movie with eerie silhouettes, stark contrasts, and a dreamlike style that feels halfway between a children’s storybook and a gothic nightmare. It’s gorgeous and terrifying in equal measure.

United Artists, The Night of the Hunter (1955)

United Artists, The Night of the Hunter (1955)

I Am Cuba (1964)

A wild collaboration between Soviet and Cuban filmmakers, this film is less narrative than visual poetry. The camera floats through Havana streets and sugarcane fields with impossible tracking shots, wide angles that bend space, and a rhythm that feels hypnotic. The result is a surreal yet stunning portrait of Cuba on the edge of revolution.

The Passion Of Joan Of Arc (1928)

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent classic is basically a close-up symphony. Joan’s face fills the screen as she’s interrogated, every tear and twitch lit with unforgiving brightness. The stripped-down sets, stark contrasts, and relentless framing put you right inside her anguish. It’s one of the most intense visual experiences in film history.

Société Générale des Films, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Société Générale des Films, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

Andrei Tarkovsky’s debut about a boy orphaned by war drifts between gritty realism and dreamlike memory. Long takes soak up every shadow on ruined buildings, every glimmer on rivers and birch trees. The black and white makes war look both bleak and strangely poetic, balancing horror with haunting beauty.

Mosfilm, Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

Mosfilm, Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

Double Indemnity (1943)

This classic noir has insurance, murder, and Barbara Stanwyck at her most dangerously glamorous. But what makes it iconic is John F. Seitz’s cinematography: slats of light cutting across rooms like prison bars, smoke curling through the shadows, and characters’ faces half-lost in darkness. It’s noir moodiness at its peak.

Paramount Pictures, Double Indemnity (1944)

Paramount Pictures, Double Indemnity (1944)

Notorious (1946)

Leave it to Hitchcock to make espionage look this gorgeous. Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant move through a world of looming staircases, intense close-ups, and dramatic lighting that mirrors the film’s tension between intimacy and danger. Even a simple shot of a key in Bergman’s hand is filmed with dizzying suspense.

RKO Radio Pictures, Notorious (1946)

RKO Radio Pictures, Notorious (1946)

Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans (1927)

FW Murnau’s silent love story is as visually lush as it is heartfelt. The camera glides and floats in ways that feel almost modern, while silhouettes and misty landscapes mirror the characters’ turmoil. When romance takes over, the light softens like a dream. It’s silent cinema at its most magical.

Fox Film Corporation, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

Fox Film Corporation, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

The Seventh Seal (1957)

A knight plays chess with Death on a bleak Scandinavian beach—what else do you need to know? Ingmar Bergman fills every frame with stark seascapes, looming shadows, and piercing silhouettes. The images are so iconic they’ve been parodied endlessly, but the original still feels like staring mortality in the face.

Svensk Filmindustri, The Seventh Seal (1957)

Svensk Filmindustri, The Seventh Seal (1957)

Raging Bull (1980)

Martin Scorsese turned Jake LaMotta’s boxing career and implosion into pure black and white fury. The fight scenes are visceral ballets of sweat and blood, with cinematographer Michael Chapman throwing harsh lights across the ring. Every bruise and bead of sweat looks monumental, and every shadow underscores the tragedy of LaMotta’s life.

United Artists, Raging Bull (1980)

United Artists, Raging Bull (1980)

Eraserhead (1977)

David Lynch’s debut is a waking nightmare: industrial landscapes, mutant babies, and existential dread. The black and white photography makes every pipe, brick, and shadow feel oppressive. The contrasts are extreme, the textures grotesque, and the atmosphere so thick you practically choke on it.

Libra Films, Eraserhead (1977)

Libra Films, Eraserhead (1977)

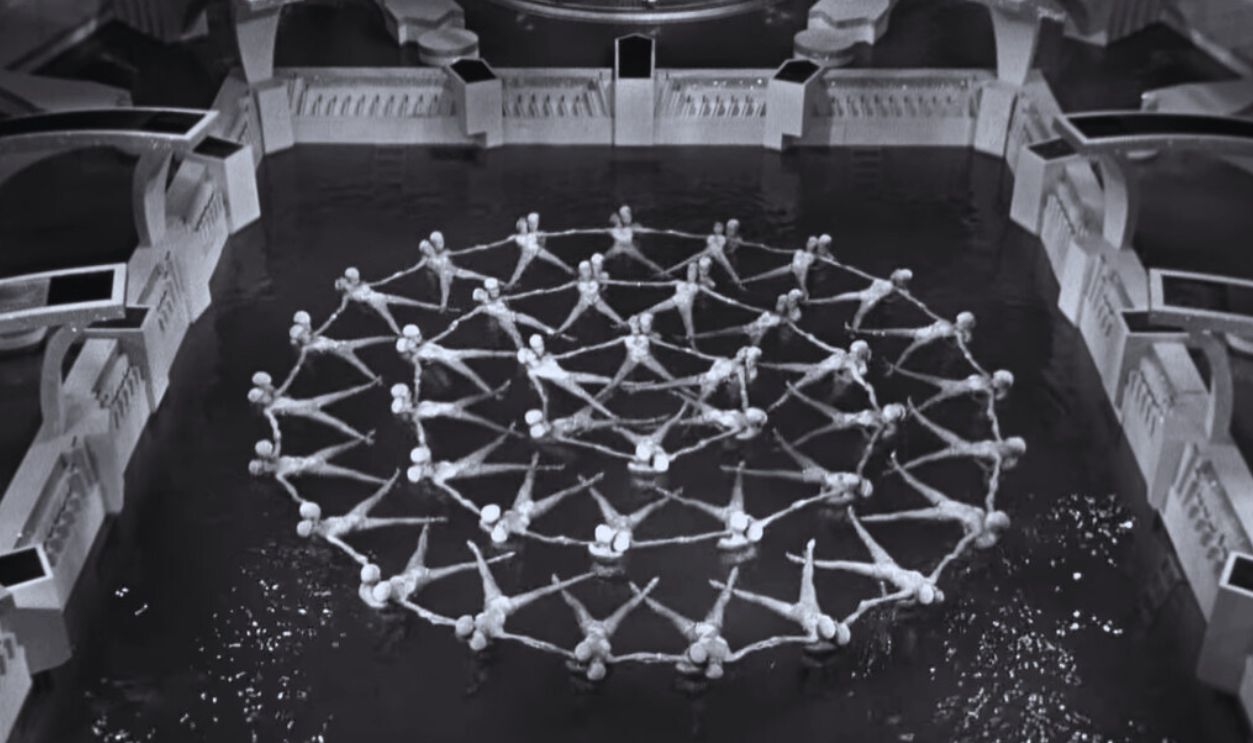

Footlight Parade (1933)

This Busby Berkeley musical about a desperate choreographer isn’t just fun—it’s dazzling. The black and white photography turns feathers, sequins, and synchronized dancers into kaleidoscopic art. The camera swoops and swirls with a fluidity that makes the musical numbers sparkle even without Technicolor.

Warner Bros. Pictures, Footlight Parade (1933)

Warner Bros. Pictures, Footlight Parade (1933)

Tokyo Story (1953)

Yasujiro Ozu’s family drama about aging parents visiting their busy children is as quiet visually as it is emotionally. The camera sits low, compositions are symmetrical and calm, and empty spaces carry as much weight as the people. The black and white feels gentle, almost meditative, amplifying the film’s heartbreak.

Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang’s futuristic epic is all towering skyscrapers, massive machines, and dystopian visions. The black and white cinematography makes the geometry of the city feel like a cathedral of steel, while shadows and smoke turn the workers’ world into a living nightmare. It’s expressionism on steroids.

UFA (Universum Film AG), Metropolis (1927)

UFA (Universum Film AG), Metropolis (1927)

La Belle Et La Bête (1946)

Jean Cocteau’s take on Beauty and the Beast transforms fairy tale into high art. The Beast’s castle glimmers with candlelit shadows, mirrors ripple like portals, and smoke drifts like enchantment. Every shot feels like a moving painting, where magic and menace blend seamlessly.

DisCina, La Belle et la Bête (1946)

DisCina, La Belle et la Bête (1946)

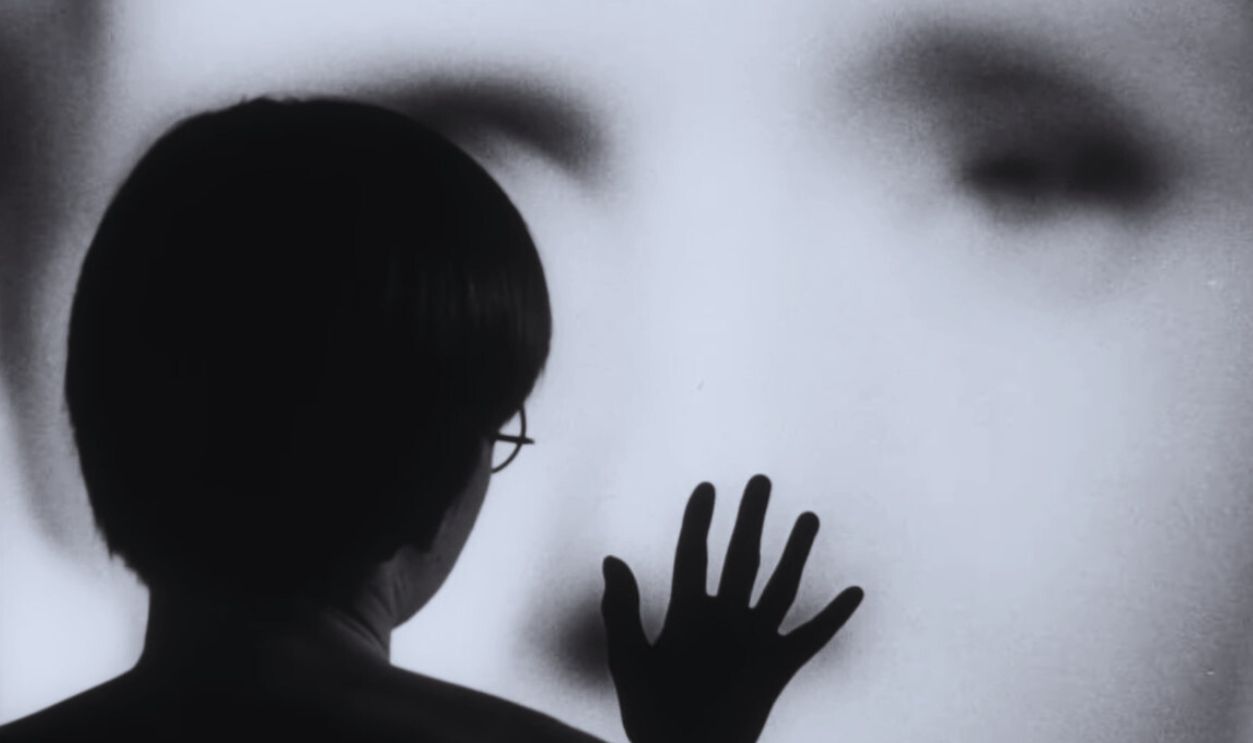

Persona (1966)

Ingmar Bergman strips cinema down to two women in a house and still makes it breathtaking. Cinematographer Sven Nykvist uses extreme close-ups, lighting that cuts across faces like a scalpel, and surreal interludes that blur reality. The visuals are so intense you feel like you’re staring straight into someone’s soul.

AB Svensk Filmindustri, Persona (1966)

AB Svensk Filmindustri, Persona (1966)

Wings Of Desire (1987)

Wim Wenders’s angels float over Berlin in luminous black and white, watching humans with quiet tenderness. Henri Alekan’s photography is soft, ethereal, and full of light that feels almost otherworldly. When the film switches to color, you realize just how magical the monochrome truly was.

Road Movies Filmproduktion, Wings of Desire (1987)

Road Movies Filmproduktion, Wings of Desire (1987)

The Grapes Of Wrath (1940)

John Ford’s Steinbeck adaptation captures the Dust Bowl migration with aching beauty. Endless highways, cracked farmland, and weathered faces are shot with a dignity that matches the story’s grit. The black and white landscapes make the journey look both hopeless and heroic.

20th Century Fox, The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

20th Century Fox, The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

The Third Man (1949)

Post-war Vienna becomes a noir playground in this thriller about mystery man Harry Lime. Robert Krasker tilts his camera until the world feels unstable, fills the screen with long shadows, and turns rain-slicked cobblestones into works of art. And of course, that iconic sewer chase is pure shadowy brilliance.

London Film Productions, The Third Man (1949)

London Film Productions, The Third Man (1949)

Rashômon (1950)

Akira Kurosawa’s tale of conflicting testimonies plays out in a forest alive with shafts of light and shadow. Sunlight streams through trees, rain pours relentlessly, and every angle feels different depending on whose truth is being told. The cinematography makes perspective itself part of the drama.

Manhattan (1979)

Woody Allen’s ode to New York is filmed like a black and white love letter. The skyline, the bridges, and even rainy sidewalks are framed with a nostalgic glow. Gordon Willis’s cinematography turns the city into a moody, romantic backdrop for tangled relationships.

United Artists, Manhattan (1979)

United Artists, Manhattan (1979)

Shanghai Express (1932)

Marlene Dietrich rides a train through civil war, and the camera worships her every move. Shadows drape across her face, steam swirls in the compartments, and the lighting makes her look like a living sculpture. The whole film oozes old Hollywood glamour and danger.

Paramount Pictures, Shanghai Express (1932)

Paramount Pictures, Shanghai Express (1932)

Black Sunday (1960)

This Italian gothic horror unleashes witches, curses, and vampire-like terrors with a painterly touch. Director Mario Bava uses flickering candles, cavernous castles, and stark close-ups to make the atmosphere thick with dread. The black and white imagery is so eerie it feels carved out of nightmares.

Galatea Film, Black Sunday (1960)

Galatea Film, Black Sunday (1960)

Dead Man (1995)

Jim Jarmusch’s existential western takes Johnny Depp through a frontier that looks more ghostly than real. Robbie Müller’s black and white photography makes forests, rivers, and plains feel mythic, like the landscape itself is judging him. It’s a western where the silence between gunshots matters as much as the violence.

Miramax Films, Dead Man (1995)

Miramax Films, Dead Man (1995)

Embrace Of The Serpent (2015)

This modern masterpiece follows two explorers decades apart, guided by the same Amazonian shaman. The monochrome cinematography captures the lush jungle with surreal intensity: light trickling through leaves, reflections rippling across rivers, and close-ups that make nature feel sacred. Proof that black and white still has fresh magic today.

Oscilloscope Laboratories, Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

Oscilloscope Laboratories, Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

You May Also Like:

The Most Iconic Black And White Films In Modern History

The 11 Most Attractive Stars From Hollywood's Black And White Era

The Greatest Black And White Movies Of All Time

Sources: 1