Not All Bad

Some great directors struggle their entire careers trying to get films made. While others somehow keep getting chance and chance despite delivering poor to mediocre results. But just like how a broken clock is right twice a day—these lesser directors have managed to make something really good once (or even twice) along the way.

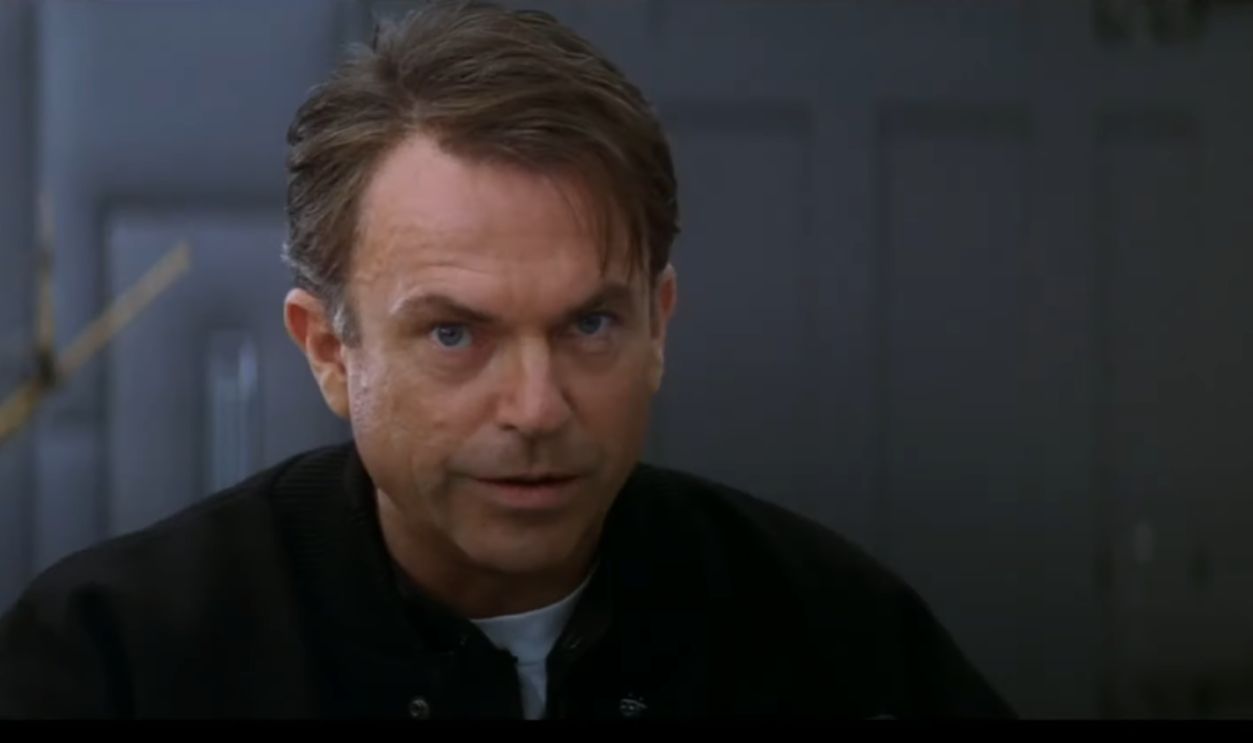

Michael Bay: "The Rock" (1996), "Pain & Gain" (2013)

Michael Bay: "The Rock" (1996), "Pain & Gain" (2013)

Bay’s career is dominated by the awful Transformers franchise and overwrought misfires like Armageddon. But on two occasions, the man actually got it right. The Rock is loud but focused, while Pain & Gain is darkly funny and self-aware. Both show a level of restraint Bay usually avoids—and prove he’s capable of coherence when he actually tries.

Screenshot from The Rock, Hollywood Pictures (1996)

Screenshot from The Rock, Hollywood Pictures (1996)

Zack Snyder: "300" (2006)

Sure, 300 is style over substance—but the style was so original and fun that it worked. The problems came afterward, when Snyder became a one-trick pony—and the trick could no longer hide the cracks. That’s how we ended up with bloated, joyless entries like Batman v Superman, Rebel Moon, and Man of Steel. This one works because it fully embraces exaggerated style. The visuals fit the simple story, the tone never wavers, and the movie doesn’t pretend to be profound. It’s dumb, confident, and honest—and that honesty saves it.

Screenshot from 300, Warner Bros. Pictures (2006)

Screenshot from 300, Warner Bros. Pictures (2006)

Paul W.S. Anderson: "Event Horizon" (1997)

Best known for empty franchise entries like Resident Evil: The Final Chapter and Monster Hunter, Anderson rarely shows restraint. Event Horizon feels like it came from someone else entirely. It’s dark, atmospheric, and genuinely unsettling. Even compromised by studio meddling, it taps into cosmic horror in a way Anderson almost never approaches again.

Screenshot from Event Horizon, Paramount Pictures (1997)

Screenshot from Event Horizon, Paramount Pictures (1997)

Brett Ratner: "Rush Hour" (1998)

Ratner followed this with disasters like X-Men: The Last Stand and the infamous Movie 43. In Rush Hour, he made one smart move—get out of the way. Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker’s chemistry does all the heavy lifting. The jokes land, the pacing is tight, and Ratner doesn’t interfere.

Screenshot from Rush Hour, New Line Cinema (1998)

Screenshot from Rush Hour, New Line Cinema (1998)

Roland Emmerich: "Independence Day" (1996)

Emmerich later doubled down on hollow spectacle with 2012 and Moonfall. Independence Day somehow balances destruction with charm. The characters are likable, the humor works, and the chaos feels earned. It’s ridiculous fun that knows exactly what it is—something his later disaster films completely forgot.

Screenshot from Independence Day, 20th Century Fox (1996)

Screenshot from Independence Day, 20th Century Fox (1996)

Joel Schumacher: "Falling Down" (1993)

Schumacher is infamous for Batman & Robin, which effectively killed the original Batman film series for years. He also delivered excess-heavy misfires like The Number 23. Falling Down is different—focused, uncomfortable, and surprisingly restrained. Michael Douglas anchors a film that explores rage instead of turning it into neon spectacle.

Screenshot from Falling Down, Warner Bros. Pictures (1993)

Screenshot from Falling Down, Warner Bros. Pictures (1993)

Len Wiseman: "Underworld" (2003)

Wiseman followed Underworld with forgettable projects like Live Free or Die Hard and Total Recall (2012). His debut works because the style finally serves the story. The gothic tone, pulpy mythology, and Kate Beckinsale’s commitment elevate what could’ve been disposable genre fluff into something cult-worthy.

Screenshot from Underworld, Screen Gems (2003)

Screenshot from Underworld, Screen Gems (2003)

McG: "Charlie’s Angels" (2000)

McG’s later work includes exhausting chaos like Terminator Salvation and other noisy, overcut action. Charlie’s Angels succeeds because it leans fully into camp. It’s ridiculous, self-aware, and powered by cast chemistry. The movie never pretends to be serious—which is exactly why it’s still fun.

Screenshot from Charlie’s Angels, Columbia Pictures (2000)

Screenshot from Charlie’s Angels, Columbia Pictures (2000)

Uwe Boll: "Rampage" (2009)

Yes—the director of House of the Dead and Alone in the Dark. Rampage is shockingly focused. It’s grim, intense, and deeply uncomfortable, but intentional. Boll drops his usual incompetence and aims for raw impact. It’s not pleasant—but it proves he could make a serious film once.

Screenshot from Rampage, Uwe Boll Productions (2009)

Screenshot from Rampage, Uwe Boll Productions (2009)

Jan de Bont: "Speed" (1994)

After Speed, de Bont delivered infamous misfires like Speed 2. His debut remains perfectly paced and relentlessly tense. The premise is simple, the execution razor-sharp, and the momentum never lets up. It’s a masterclass in efficiency—and a reminder that sometimes a director peaks immediately.

Screenshot from Speed, 20th Century Fox (1994)

Screenshot from Speed, 20th Century Fox (1994)

Duncan Jones: "Moon" (2009)

Jones followed Moon with confused projects like Warcraft and Mute. His debut remains intimate, thoughtful, and character-driven. Anchored by a strong central performance, Moon proves Jones understands restrained sci-fi storytelling. That focus disappeared later, making this feel like a glimpse of unrealized potential.

Screenshot from Moon, Sony Pictures Classics (2009)

Screenshot from Moon, Sony Pictures Classics (2009)

Richard Kelly: "Donnie Darko" (2001)

Kelly chased this success with overstuffed disasters like Southland Tales and The Box. Donnie Darko works because it embraces ambiguity. The mystery feels emotional instead of pretentious, and the tone stays locked in. Everything afterward tried to explain too much. This one succeeded precisely because it didn’t.

Screenshot from Donnie Darko, Newmarket Films (2001)

Screenshot from Donnie Darko, Newmarket Films (2001)

Alex Proyas: "Dark City" (1998)

Proyas later stumbled with uneven efforts like I, Robot and Gods of Egypt. Dark City remains his high point. The noir-meets-sci-fi aesthetic is striking, the atmosphere heavy, and the ideas inventive without becoming incomprehensible. His best concept arrived early—and never got topped.

Screenshot from Dark City, New Line Cinema (1998)

Screenshot from Dark City, New Line Cinema (1998)

Joe Johnston: "The Rocketeer" (1991)

Johnston’s résumé includes competent but forgettable studio work like Jurassic Park III and The Wolfman. The Rocketeer stands out for its sincerity. It’s earnest, charming, and proudly old-fashioned, with real heart and pulpy adventure energy. Most of Johnston’s later work never felt this personal or memorable.

Screenshot from The Rocketeer, Walt Disney Pictures (1991)

Screenshot from The Rocketeer, Walt Disney Pictures (1991)

Peter Berg: "Friday Night Lights" (2004)

Berg often mistakes volume for depth, as seen in Battleship and Lone Survivor. Friday Night Lights is quieter and more human. It focuses on character, pressure, and small-town expectations instead of nonstop bombast. The restraint pays off, making it his most emotionally effective film.

Screenshot from Friday Night Lights, Universal Pictures (2004)

Screenshot from Friday Night Lights, Universal Pictures (2004)

Rob Zombie: "The Devil’s Rejects" (2005)

Zombie usually lets excess overwhelm everything, as in Halloween II or 3 from Hell. The Devil’s Rejects channels that chaos into something focused and brutal. It’s ugly, mean, and uncomfortable—but coherent. When Zombie leans into character instead of shock alone, the result actually works.

Screenshot from The Devil’s Rejects, Lionsgate (2005)

Screenshot from The Devil’s Rejects, Lionsgate (2005)

Josh Trank: "Chronicle" (2012)

Trank followed Chronicle with the infamous collapse of Fantastic Four. His debut remains tight, emotional, and inventive. The found-footage approach feels natural, and the character arc hits hard. Nothing since has matched its focus or impact. It’s a career peak that arrived immediately—and vanished just as fast.

Screenshot from Chronicle, 20th Century Fox (2012)

Screenshot from Chronicle, 20th Century Fox (2012)

Michael Cimino: "The Deer Hunter" (1978)

Cimino followed this Best Picture winner with Heaven’s Gate, one of the most infamous disasters in film history. The Deer Hunter is focused, emotional, and technically impressive. Nothing else in his career comes close. One masterpiece—and a collapse so massive it permanently changed Hollywood.

Screenshot from The Deer Hunter, Universal Pictures (1978)

Screenshot from The Deer Hunter, Universal Pictures (1978)

Bob Clark: "Black Christmas" (1974)

Clark’s filmography somehow includes both Black Christmas and Baby Geniuses. His early slasher is tense, influential, and genuinely creepy. Everything later veered into baffling family fare and outright disasters. It’s one of the clearest examples of a director peaking early—and never returning.

Screenshot from Black Christmas, Warner Bros. (1974)

Screenshot from Black Christmas, Warner Bros. (1974)

Joe Dante: "Gremlins" (1984)

Dante made plenty of cult oddities, but Gremlins towers over the rest. It balances horror and comedy with restraint, plus just enough chaos to feel dangerous. Later projects like Small Soldiers never matched this tight, playful sweet spot.

Screenshot from Gremlins, Warner Bros. Pictures (1984)

Screenshot from Gremlins, Warner Bros. Pictures (1984)

Andrew Davis: "The Fugitive" (1993), "Under Siege" (1992)

After these hits, Davis delivered forgettable action films like Chain Reaction and Collateral Damage. For a brief moment, though, he was on a roll. Under Siege is a tight, old-school action thriller, and The Fugitive is near-perfect studio filmmaking. After that? The magic vanished fast.

Screenshot from The Fugitive, Warner Bros. Pictures (1993)

Screenshot from The Fugitive, Warner Bros. Pictures (1993)

Rob Marshall: "Chicago" (2002)

Marshall followed Chicago with lifeless misfires like Nine and Mary Poppins Returns. Chicago works because it’s sharp, stylish, and disciplined, with musical numbers that feel purposeful instead of indulgent. It’s the rare case where restraint elevated spectacle.

Screenshot from Chicago, Miramax Films (2002)

Screenshot from Chicago, Miramax Films (2002)

Renny Harlin: "The Long Kiss Goodnight" (1996)

Harlin directed Die Hard 2, the weak link between Die Hard and Die Hard with a Vengeance—both helmed by John McTiernan. His career also includes disasters like Cutthroat Island and Deep Blue Sea. The Long Kiss Goodnight, however, is a sharp, fun, and totally underrated action film.

Screenshot from The Long Kiss Goodnight, Columbia Pictures (1996)

Screenshot from The Long Kiss Goodnight, Columbia Pictures (1996)

Michael Lehmann: "Heathers" (1988)

Lehmann followed Heathers with misfires like Hudson Hawk and Airheads. His cult classic works because it perfectly balances pitch-black satire with genuine teen angst. Everything else leaned broader and messier. Heathers remains the one time Lehmann’s tone, timing, and material aligned just right.

Screenshot from Heathers, New World Pictures (1989)

Screenshot from Heathers, New World Pictures (1989)

You Might Also Like:

Times That American Cinema Butchered A Beautiful Foreign Film

Before They Were Classics, Test Audiences Absolutely Hated These Films