The End Of An Era: The Day The Music Died

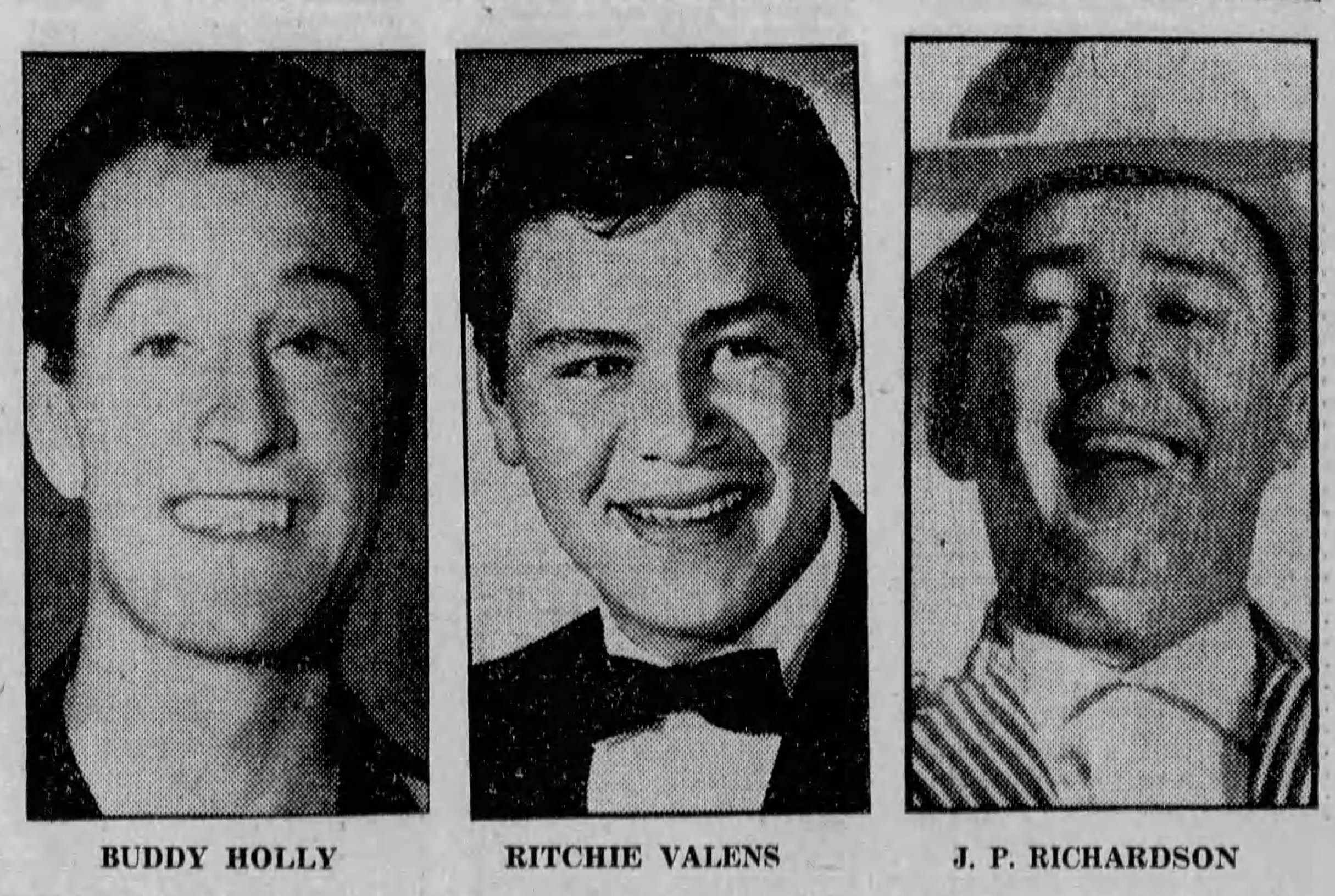

Rock and roll started emerging in the United States in the 1940s. By the mid-1950s, it had evolved into a distinct sound. This era of rock and roll was defined by artists like Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper.

But it couldn't last forever.

The Times They Are A Changin'

By the late 1950s, there was a distinct shift in rock and roll. The artists who had been popular in the 1950s started losing ground to newer sounds and more polished artists. While some artists—like Lewis and Berry—fell from public favor because of their personal lives, others left the rock and roll scene for other reasons.

Most notably, Holly, Valens, and The Big Bopper tragically perished in a plane crash on the day the music died.

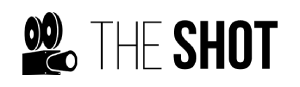

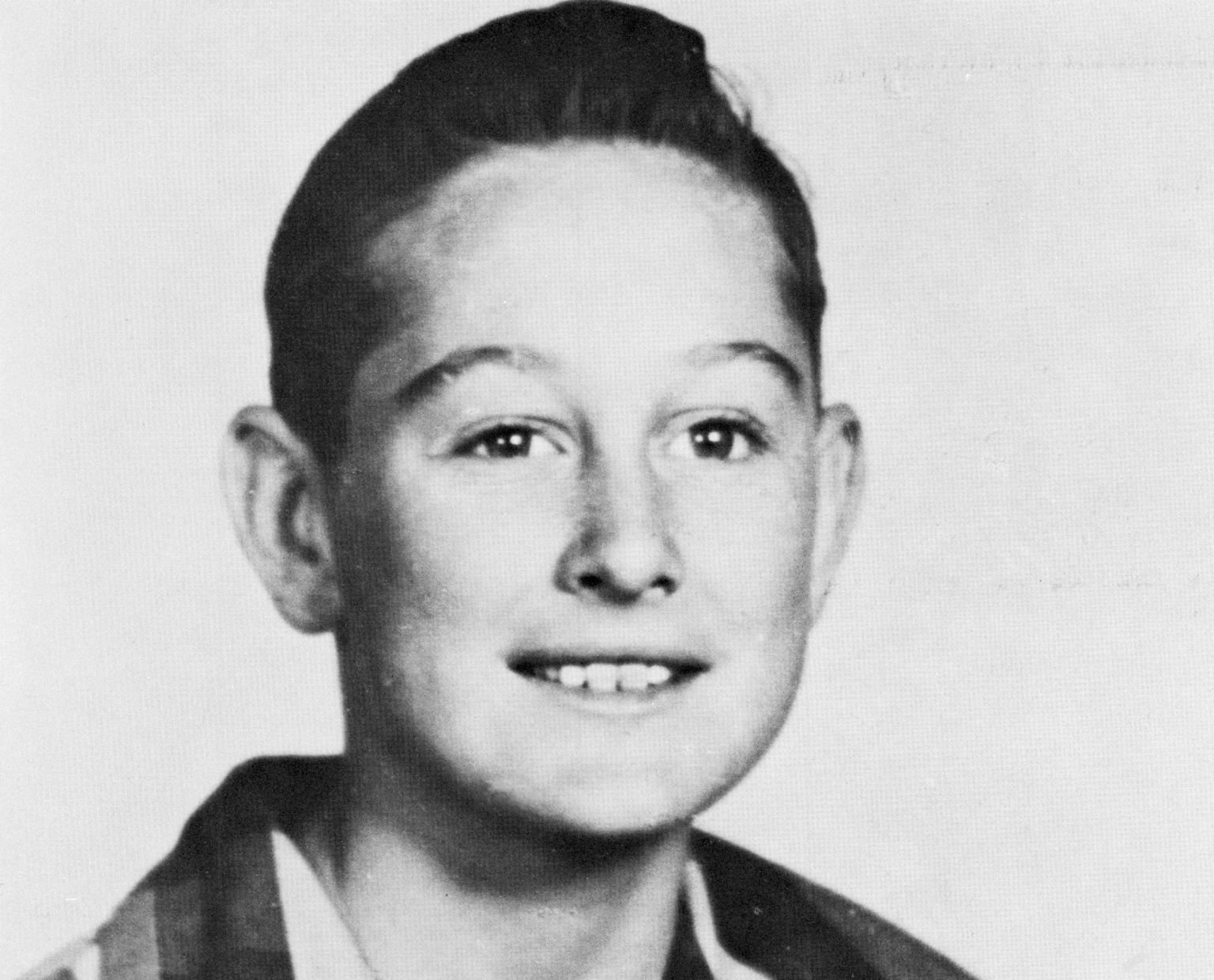

Brunswick Records, Wikimedia Commons

Brunswick Records, Wikimedia Commons

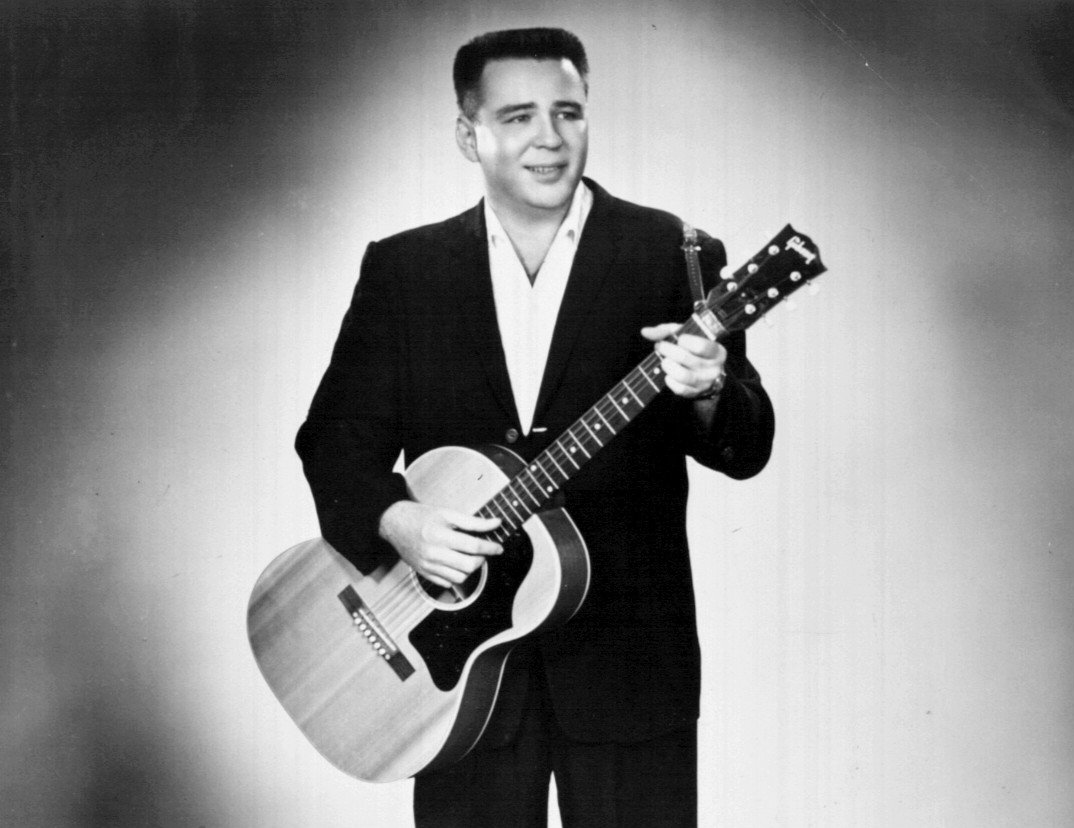

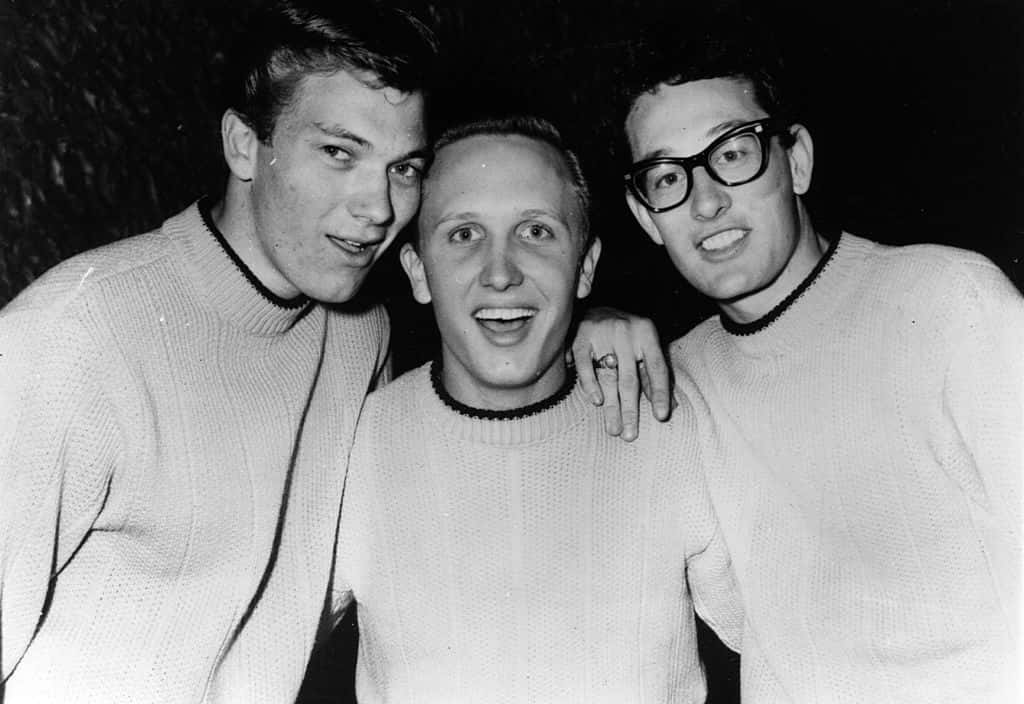

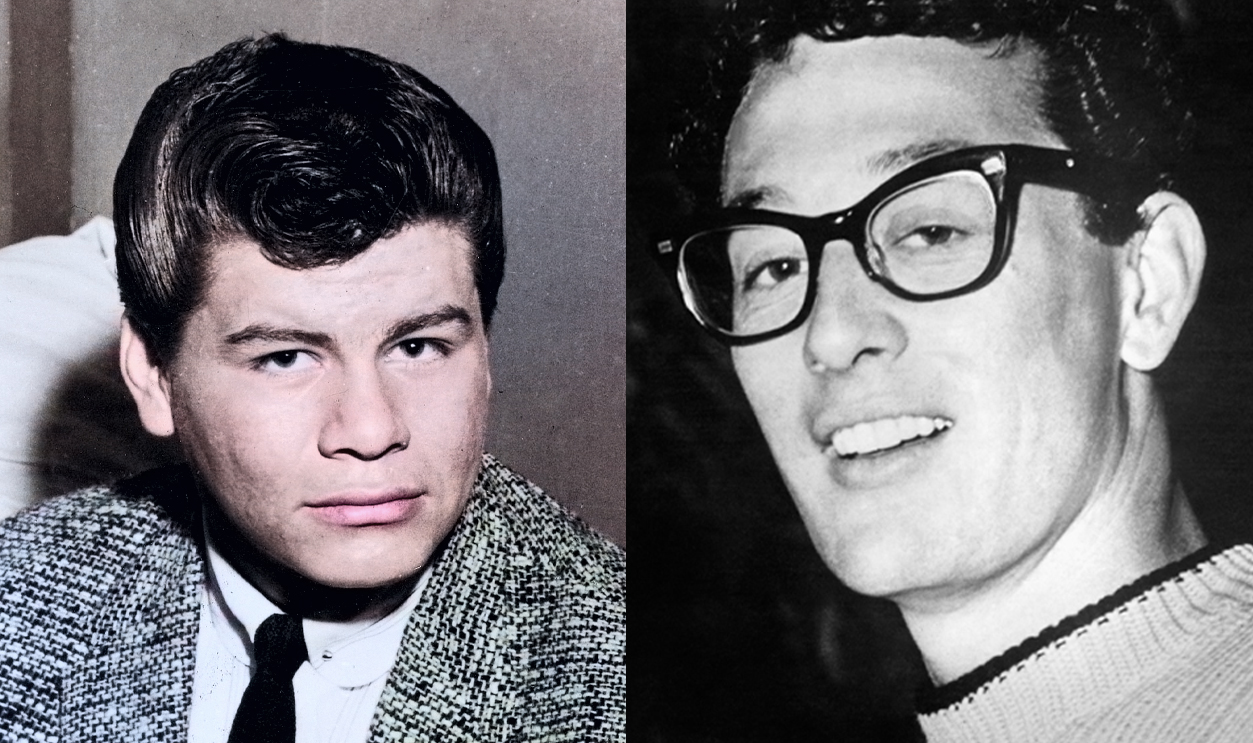

Buddy Holly’s Career Spanned 20 Months

For two short years—from 1957 to 1958—Buddy Holly was the frontman for one of America’s biggest musical acts, the Crickets. While some 1950s radio DJs referred to the band as “Buddy Holly and the Crickets”, that was technically incorrect. Holly’s record labels never used “Buddy Holly and the Crickets” until after his passing.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

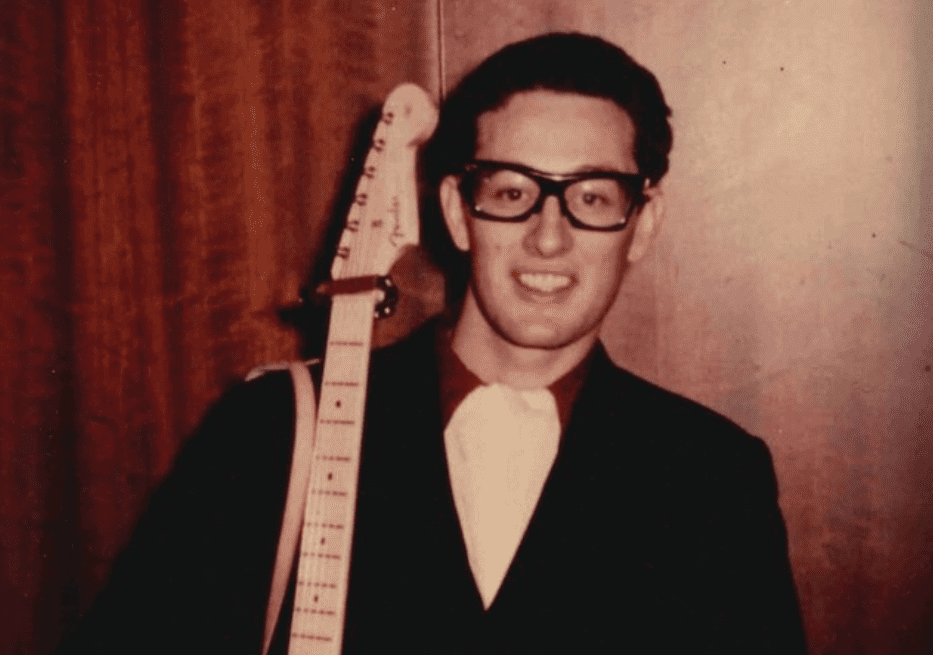

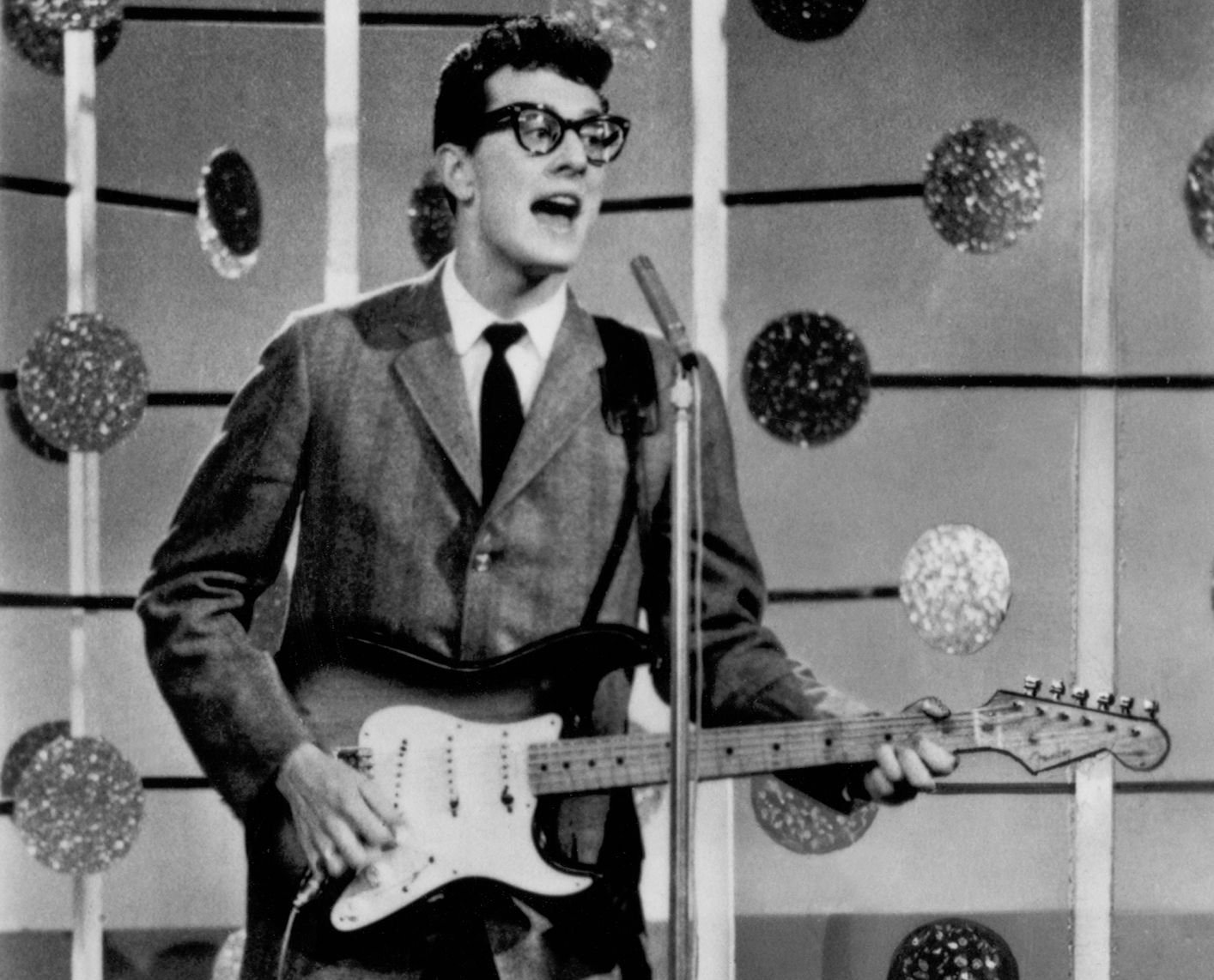

His Biggest Hits

Holly had a string of hits in the late 1950s. Besides his 1957 breakout hit, “That’ll Be The Day”, Holly recorded chart toppers like “Peggy Sue”, “Everyday”, and “Maybe Baby”.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

His Split From The Crickets

In late 1958, Holly parted ways with the Crickets and their manager. His parting from the Crickets was amicable. After discovering the New York scene, Holly wanted to make his home in the Big Apple. The Crickets were content to remain based in Lubbock, Texas.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

The Crickets’ Manager Stole From The Band

Holly’s break with the Crickets’ manager—Norman Petty—was not as amicable. In mid-1958, Holly discovered that Petty was siphoning off royalties from the Crickets. Holly retained a lawyer but Petty was unable to pay the money back. This squabble was just the start of the bespectacled rocker’s money woes.

Evening Standard, Getty Images

Evening Standard, Getty Images

Holly’s Financial Woes Mounted

Around the same time as the court battle with Petty, Holly was sued by a New York concert promoter named Manny Greenfield, who believed he was entitled to a larger cut of the singer’s booking earnings. When Holly refused, Greenfield sued him, which froze Holly’s royalty payments. With no money coming in, Holly had to figure out how to pay his bills.

General Artists Corporation, Getty Images

General Artists Corporation, Getty Images

He Agreed To Headline The Winter Dance Party Tour

Holly signed with General Artists Corporation (GAC), a talent booking agency. He agreed to headline a short tour across the American Midwest in early 1959, billed as the Winter Dance Party Tour.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

He Needed A New Band

Without the Crickets, Holly needed a new backing band. Along with session artist Tommy Allsup on guitar and Carl Bunch on drums, Holly hired an unknown musician to play bass. That musician would later become one of the founders of outlaw country in the 1970s.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

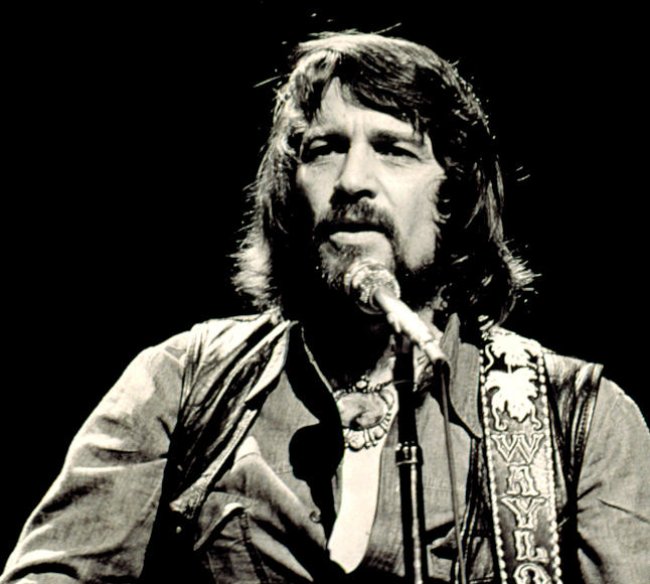

Waylon Jennings And Holly Were Old Friends

Holly met Waylon Jennings in the early 1950s, while Holly was still in high school. At the time, Holly had a country music act called Buddy and Bob, which played a regular live show every Sunday on a radio station in Lubbock, Texas where Jennings was a DJ.

RCA Records, Wikimedia Commons

RCA Records, Wikimedia Commons

Holly Produced Jennings’ First Two Singles

The friendship between Holly and Jennings continued as Holly’s star rose. In late 1958, Holly produced Jennings’ first two singles, "Jole Blon" and "When Sin Stops (Love Begins)”.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

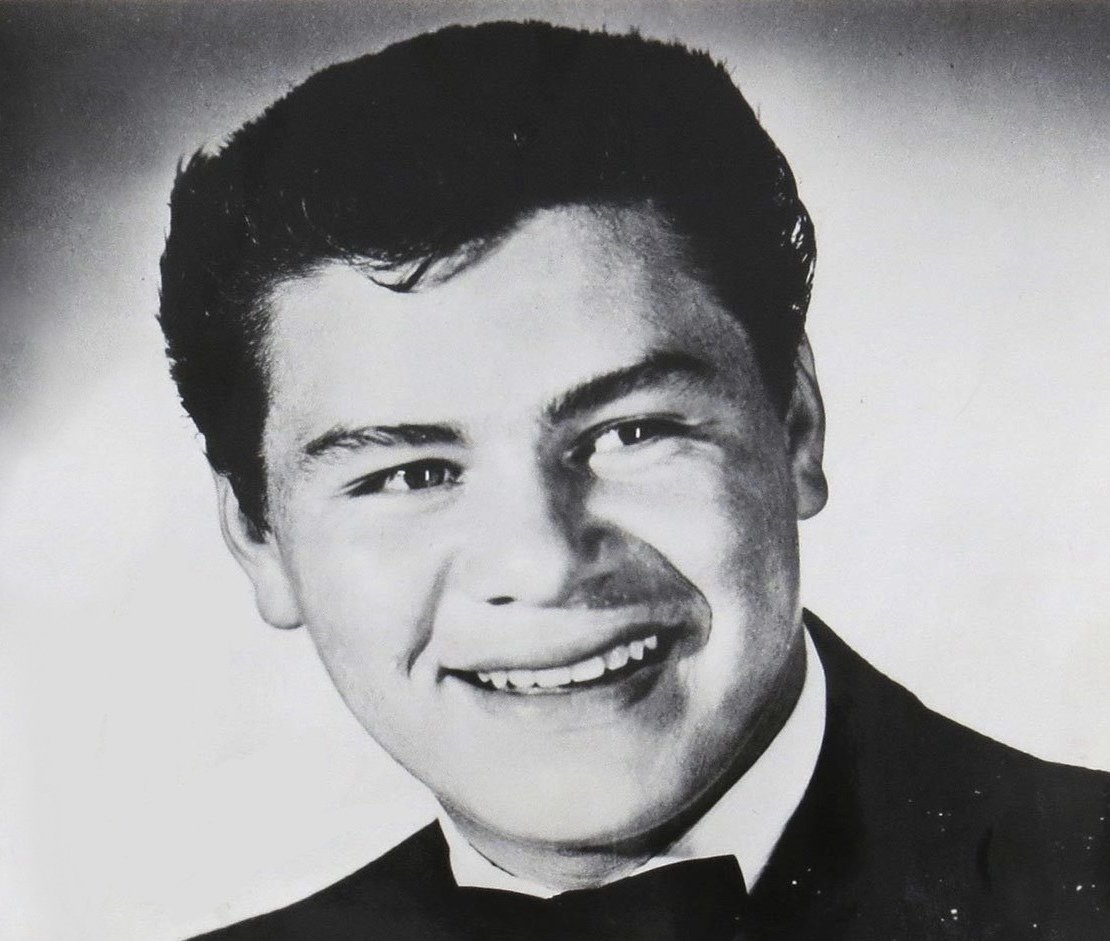

Frankie Sardo Was Recruited As The Opening Act

In addition to a backing band for Holly, the tour needed supporting acts. Holly brought on Frankie Sardo as the opening act. Sardo had just released his second song, “Fake Out”, which became his breakout hit.

Dion And The Belmonts Joined The Tour

Dion and the Belmonts were a vocal doo-wop quartet from the Bronx, New York City. They had achieved success with three Top 40 hits in 1958. Late that year, they completed their first tour as one of the supporting acts for Holly, the Coasters, and Bobby Darin.

ABC Records, Wikimedia Commons

ABC Records, Wikimedia Commons

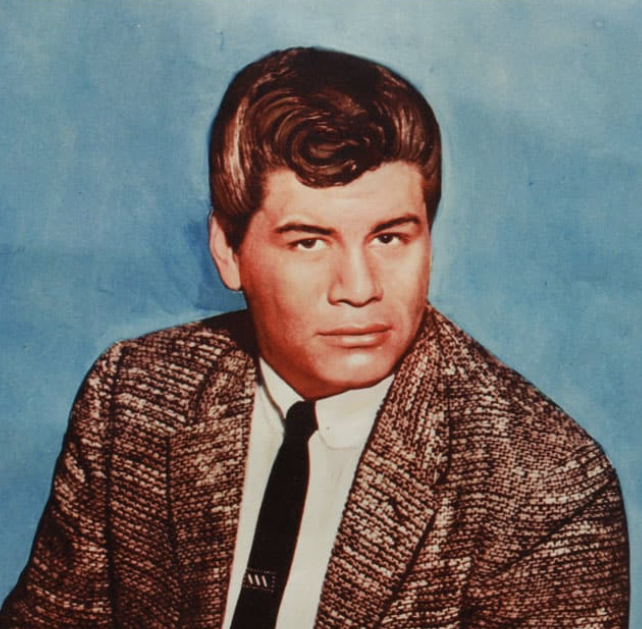

17-Year-Old Ritchie Valens Had Star Power

Ritchie Valens was also just breaking out as an artist. In 1958, while still in high school, Valens recorded a couple of 45” records. The second record, which featured “La Bamba” with “Donna” on the B-side, sold over a million copies and launched him to stardom. He was just 17 years old when the Winter Dance Party Tour started.

General Artists Corportation, Wikimedia Commons

General Artists Corportation, Wikimedia Commons

The Big Bopper Rounded Out The Bill

Jiles Perry "J.P." Richardson Jr. chose the stage name The Big Bopper because of a dance craze in the mid-1950s called The Bop. He was also newly famous. His breakout song, “Chantilly Lace," dropped in 1958 and spent 22 weeks on the Top 40.

The Tour Kicked Off In Milwaukee

The artists gathered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to kick off the tour on January 23, 1959. The tour schedule, organized by GAC, the talent booking agency, was grueling. The bands were booked to perform in 24 different cities on 24 subsequent days, with no days off. But the relentless tour schedule wasn’t the biggest hardship the musicians faced.

BBC, The Real Buddy Holly Story (1985)

BBC, The Real Buddy Holly Story (1985)

The Tour Buses Were Terrible

The “tour buses” weren’t the kind of buses used by touring acts today. They were reconditioned school buses. Many of them had major mechanical issues. Malfunctioning bus after bus was replaced and the tour was likely on its fifth bus when it arrived at its eleventh stop at Clear Lake, Iowa. But that wasn’t the only problem with the buses.

The Buses Were Freezing Cold

The buses had insufficient heating systems for the harsh Midwest winters. When one of the buses stalled in the middle of the night, the musicians burned newspapers in an attempt to stay warm. Even so, Bunch, Holly’s drummer, was hospitalized with frostbitten feet because of the conditions on the buses.

The Tour Zigzagged Across The Midwest

As if the gruelling schedule and broken-down buses weren’t problematic enough, whoever booked the tour did not logically arrange the stops. Instead of creating a loop through the region, the tour zigzagged back and forth.

Hundreds Of Miles Between Tour Stops

The band travelled over 400 miles between some stops, logging 10-12 hours per day on those unheated buses. When the musicians arrived in Clear Lake, Iowa, they realized that the next venue was in Moorhead, Minnesota. Not only was Moorhead 365 miles from Clear Lake, but the route passed through two towns the tour had already performed in.

CBS, The Ed Sullivan Show (1948-1971)

CBS, The Ed Sullivan Show (1948-1971)

No Road Crew

On top of everything else, there was no road crew on the tour. The musicians had to unload, set up, take down, and load up their equipment each night.

Brunswick Records, Wikimedia Commons

Brunswick Records, Wikimedia Commons

The Musicians Got Sick

The long drives, unheated buses, cramped quarters, and exhaustion took their toll on the performers. Holly, Valens, and Richardson (The Big Bopper) soon had flu symptoms.

CBS, The Ed Sullivan Show (1948-1971)

CBS, The Ed Sullivan Show (1948-1971)

Holly Needed To Do Laundry

By the time their bus rolled into Clear Lake, Iowa on February 2, Holly was frustrated. They had just driven 350 miles from Green Bay, Wisconsin. They faced another 365-mile drive to their next tour stop immediately following the Clear Lake show. Holly was sick and wanted to do his laundry. So, he made one of music’s most ill-fated decisions.

Coral Records, Wikimedia Commons

Coral Records, Wikimedia Commons

He Decided To Charter A Plane To The Next Tour Stop

The musicians arrived in Clear Lake less than two hours before the show was scheduled to begin at the Surf Ballroom. Holly approached the manager of the Surf, Carroll Anderson, and asked about chartering a plane to the next tour stop.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getti Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getti Images

A Young Local Pilot Agreed To Fly

Anderson knew the owner of Dwyer Flying Service, based in nearby Mason City. When Anderson wasn’t able to reach Hubert Dwyer himself, he called one of the pilots—Roger Peterson—directly. The 21-year-old pilot agreed to fly the musicians to Fargo, North Dakota, the nearest airfield to Moorehead, Minnesota.

His aircraft was a 1947 Beechcraft Bonanza plane, which seated three passengers in addition to the pilot.

Bill Larkins, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bill Larkins, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Holly’s Phone Call To His Wife

Meanwhile, at the Surf, Holly called his wife, Maria, who was at home. Maria had accompanied Holly on past tours, but this time she was pregnant and Holly insisted that she stay home. At the time of the phone call, she was six months into her pregnancy.

Three Musicians Boarded The Plane

After the show, three musicians went out to the Mason City Municipal Airport to board their chartered flight. Initially, Holly was supposed to fly with members of his own band—his guitarist, Allsup, and his bassist, Jennings. But neither Allsup nor Jennings got on the flight.

The Vancouver Sun, Wikimedia Commons

The Vancouver Sun, Wikimedia Commons

Valens Won A Seat On A Coin Toss

Valens was sick with influenza. He approached Allsup and suggested a coin toss in an attempt to get Allsup’s seat. Allsup agreed and Valens called heads. Valens won. He reportedly said, "That's the first time I've ever won anything in my life”.

Hal Roach Studios, Wikimedia Commons

Hal Roach Studios, Wikimedia Commons

Richardson Asked For Jennings’ Seat

Richardson—The Big Bopper—was also sick. He didn’t want to get back on a cold bus for another long drive. Richardson asked Jennings if he could have Jennings’ seat on the flight. Jennings agreed.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Jennings’ Joke Haunted Him For The Rest Of His Life

When Jennings told Holly that he had given up his seat, Holly said in jest, “Well, I hope your...bus freezes up”. Jennings joked back: “Well I hope your ol’ plane crashes”. That comment haunted Jennings for the rest of his life.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Peterson Wasn’t Told About Worsening Weather

The weather that night was poor. At the airport, the conditions were reported as light snow with an obscured sky, visibility of six miles, and windspeeds of 20-30 mph. Conditions were expected to worsen along the route, but none of that weather information was relayed to Peterson before take off.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

The Flight Took Off At 12:55 A.M.

The flight with Holly, Valens, and Richardson took off at 12:55 a.m. CST on February 3 with Peterson at the controls.

The Plane’s Tail Light Disappeared

Dwyer, the owner of the flying service, watched the plane take off from the airport. He tracked the plane’s tail light as the aircraft climbed about 800 feet and then turned left twice, into a northwesterly heading. Dwyer watched as the tail light started descending before it disappeared.

Radio Contact Was Lost

After only a few minutes in the air, Peterson was no longer responsive to radio contact. Repeated attempts were made to establish contact until daylight, without success.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

The Plane Crashed Six Miles From The Airport

In the early daylight hours of February 3, Dwyer set out to retrace the aircraft’s flight path. Around 9:35 am, Dwyer found the plane’s wreckage mangled in a cornfield less than 6 miles from the airport.

Dsapery, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dsapery, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Wreckage Was Horrendous

The plane had crashed at high speed—estimated at 170 mph. The resulting wreckage was extreme. The three musicians were ejected from the aircraft and their bodies lay nearby. Peterson’s body remained entangled in the cockpit. All four perished on impact.

Civil Aeronautics Board, Wikimedia Commons

Civil Aeronautics Board, Wikimedia Commons

Pilot Error Caused The Crash

Early reports suggested that the inclement weather caused the crash. But, in a report released in September 1959, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) blamed the crash on pilot error.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Peterson Didn’t Understand The Instrument Readings

Although Peterson had over four years of flying experience, logging 711 flying hours, he was not qualified to fly in conditions where he would have to rely solely on instruments. And there was one critical issue with the instruments in the Beechcraft Bonanza that would have confused Peterson.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Peterson Trained With Different Instruments

When Peterson worked through his instrument training, he practiced on airplanes with conventional artificial horizon indicators. But the Beechcraft Bonanza had an older instrument that provided the same type of information—a Sperry F3 attitude gyroscope.

There is a critical difference between an artificial horizon indicator and a Sperry F3 attitude gyroscope—and that difference proved fatal to three of America’s most promising up-and-coming musicians and their pilot.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Peterson Wrongly Believed The Plane Was Climbing

While an artificial horizon indicator and a Sperry F3 attitude gyroscope provide the same aircraft pitch attitude information, they display that information in directly opposite ways. As a result, Peterson believed the aircraft was climbing when it was in fact descending. And with the darkness and swirling snow, he had no external visual reference points.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Maria Holly Miscarried After Hearing The News

News of the accident broke with catastrophic results. Holly’s wife Maria heard about the crash from a TV news report. She miscarried the next day.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Funerals Were Held Individually

Funerals were held individually for each of the deceased in the aftermath of the crash. Holly and Richardson were buried in their home state of Texas while Valens’ body was taken to California for his funeral. Peterson was laid to rest in Iowa.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

The Show Must Go On

Despite the horrific loss of life and the grief of the other performers on the tour, GAC mandated that the Winter Dance Party continue. Other musicians were brought in to replace those who had passed on.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

The Day The Music Died

In 1971, Don McLean recorded and released “American Pie” on an album of the same name. The phrase “the day music died” repeats throughout the song as a reference to the crash and the end of the earliest era of rock and roll. That phrase has become a popular way to refer to the crash.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Incredible Influence And Loss

The cultural loss of three promising young artists cannot be measured. Although Holly released only three albums in a 20-month span, he had an enormous impact on music. The Beatles chose their name as a reference to the Crickets. And Holly’s music influenced countless other musicians, including The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen. It’s difficult to imagine how different our musical landscape would be if Holly, Richardson, and Valens had lived long and fruitful lives.

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story

Innovisions, The Buddy Holly Story