The Other Side Of The Story

Those so-called villains of the 1980s weren’t always plotting world domination. Some were just following rules, protecting turf, or making rational choices. Once you hear their side, you might wonder if the “heroes” really had it right.

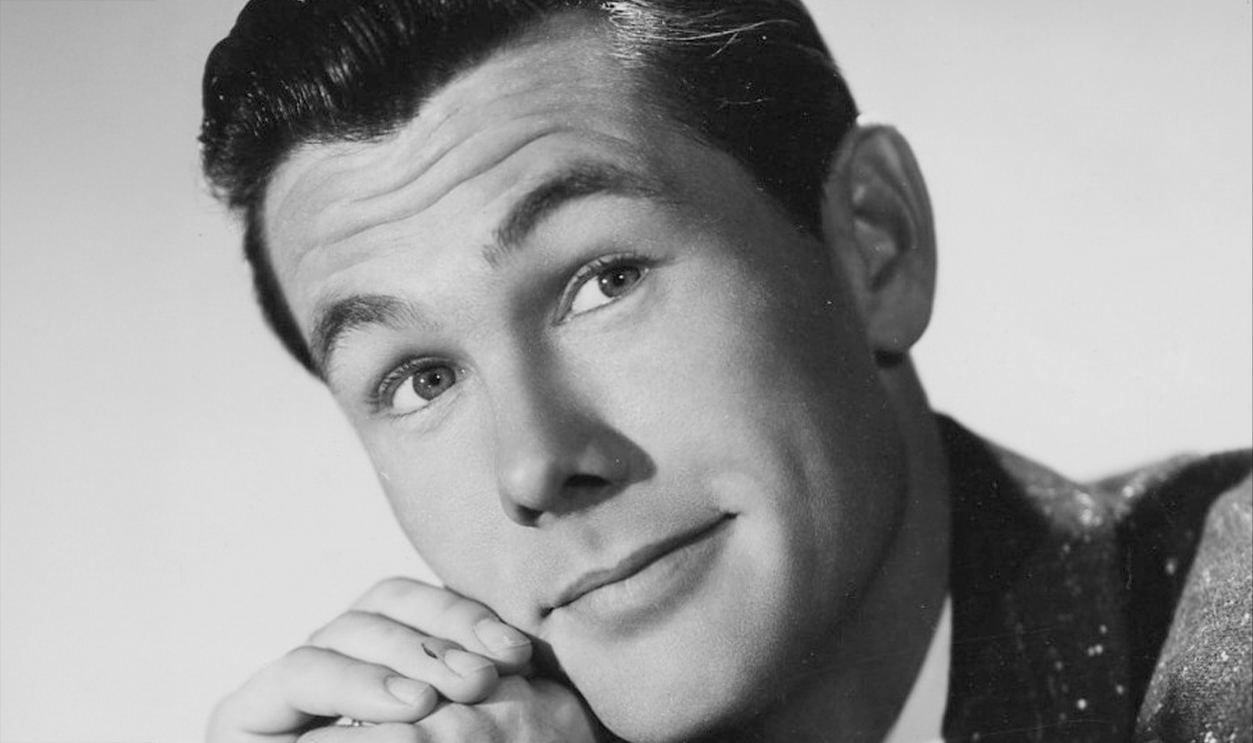

The Principal In The Breakfast Club (1985)

Detention made Vernon the face of authority, and audiences saw cruelty in every threat. Locking Bender in a closet and venting bitterness to janitor Carl exposed flaws. Still, his mission echoed accountability and responsibility—reminding students that rebellion collides with rules.

Universal Pictures, The Breakfast Club (1985)

Universal Pictures, The Breakfast Club (1985)

Walter Peck In Ghostbusters (1984)

Walter Peck appears as the film’s secondary antagonist. His environmental mandate was genuine, but his confrontational style and refusal to listen made him seem villainous. Although he obtained a court order, his impulsive shutdown of the containment unit led to chaos that exposed ego more than duty.

Columbia Pictures, Ghostbusters (1984)

Columbia Pictures, Ghostbusters (1984)

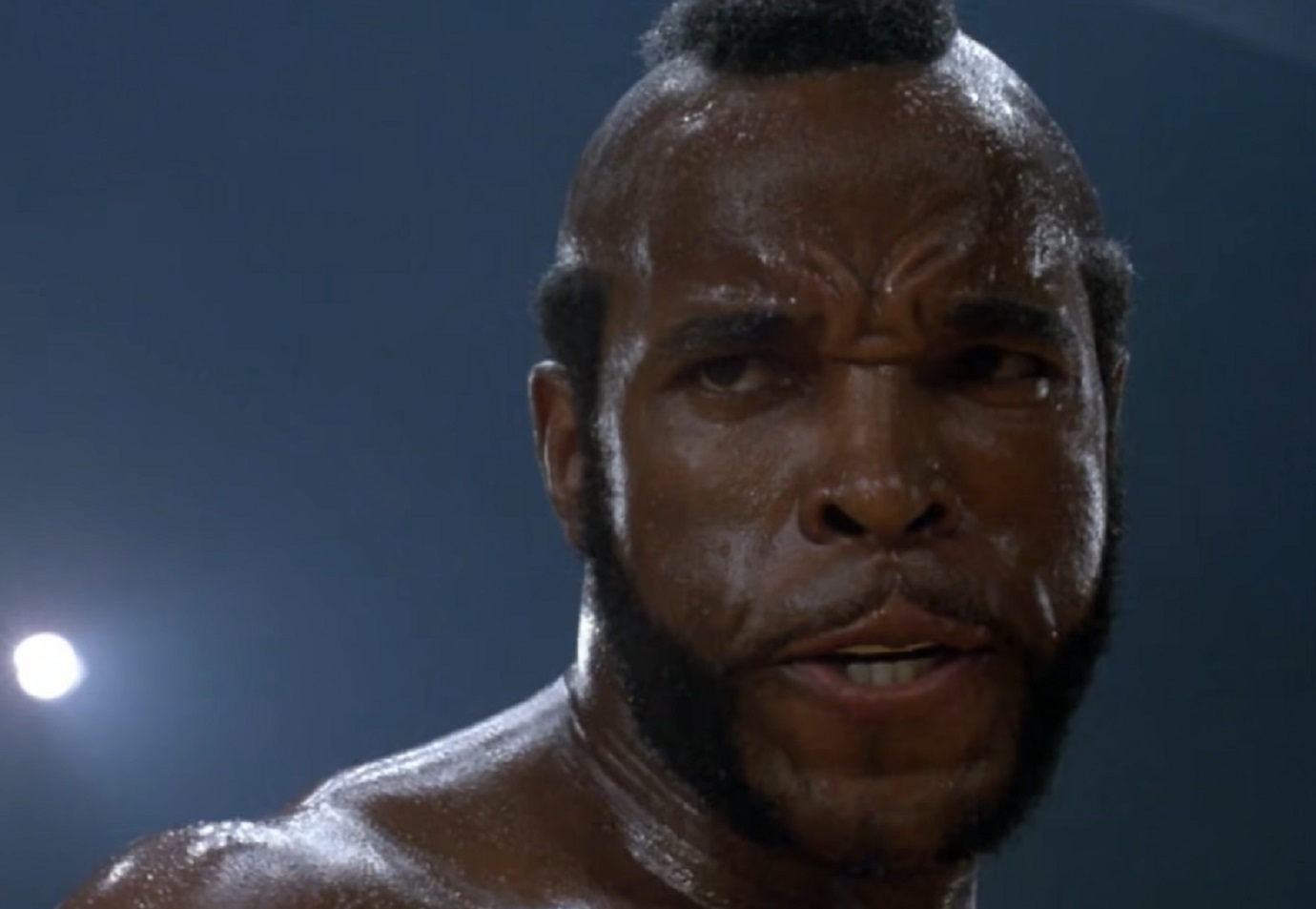

Clubber Lang In Rocky III (1982)

Aggression filled the ring, but it was Rocky’s unpreparedness that cracked under Clubber Lang’s fists. Lang had earned his place through legitimate contests. What seemed like villainy was really hunger, and his victory made one point clear: boxing respects perseverance and readiness more than reputation.

United Artists, Rocky III (1982)

United Artists, Rocky III (1982)

Roy Batty In Blade Runner (1982)

This “villain” resists the simple label of villain at all. As a Nexus-6 replicant designed for combat in off-world colonies, but shackled with a four-year lifespan to prevent the very thing that made him dangerous: emotional growth. His return was not a mission of destruction but a plea for more life.

Warner Bros., Blade Runner (1982)e Runner (1982), Warner Bros.

Warner Bros., Blade Runner (1982)e Runner (1982), Warner Bros.

Roy Batty In Blade Runner (1982) (Cont.)

So, when that was denied, his fury culminated in Tyrell’s death—an act of existential rage rather than senseless violence. What makes Roy unforgettable, though, is how, after hunting the man tasked with killing him, he chooses mercy over vengeance, saving his enemy in his final moments.

Warner Bros., Blade Runner (1982)

Warner Bros., Blade Runner (1982)

Lo Pan In Big Trouble In Little China (1986)

Cursed by China’s first emperor, Lo Pan lingered as neither alive nor dead in Big Trouble in Little China. To break free, he sought a green-eyed bride. What audiences saw as dark sorcery reflected his desperate attempt to escape an eternity of cursed existence.

20th Century Fox, Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

20th Century Fox, Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

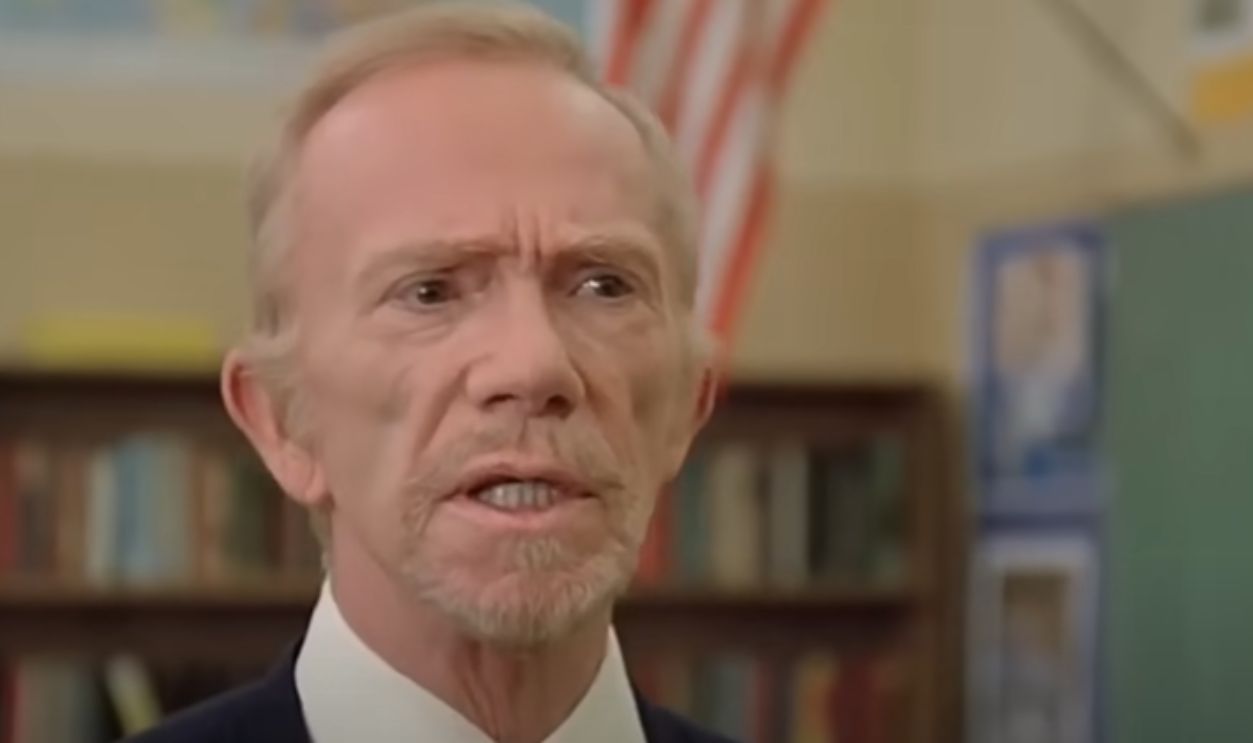

Principal Ed Rooney In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986)

Ed Rooney, the principal in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, looked obsessed, but he was doing his job. Nine unexcused absences and phony excuses gave him grounds. Rooney chased Ferris through policy, not power, though Ferris’s schemes made the authority figure look hilariously outmatched.

Paramount Pictures, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986)

Paramount Pictures, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986)

The Kurgan In Highlander (1986)

The Kurgan followed the Immortal Game’s rule of hunting other immortals for their Quickening, despite his methods going far beyond that code. He terrorized civilians and used fear as a weapon. His menace was undeniable, yet rooted in calculated intimidation.

20th Century Fox, Highlander (1986)

20th Century Fox, Highlander (1986)

The Red Lectroids In The Adventures Of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension (1984)

Banished into the 8th Dimension, a strange parallel universe, the Red Lectroids clawed for escape. Humans saw lunatics in wigs, shouting nonsense, but their disguises through Yoyodyne, a fake company, masked desperation. What looked like a farce was just aliens trying to reclaim freedom.

20th Century Fox, The Adventures Of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension (1984)

20th Century Fox, The Adventures Of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension (1984)

Lord Humungus In Mad Max 2 (1981)

Across the scorched highways of Mad Max 2, Lord Humungus appeared every bit the savage warlord. Humungus’s first act, however, was offering fuel deals and safe passage. Misread as bloodthirsty, his negotiations revealed a preference for uneasy order instead of reckless slaughter.

Warner Bros., Mad Max 2 (1981)

Warner Bros., Mad Max 2 (1981)

The Skeksis In The Dark Crystal (1982)

The Skeksis were unforgettable—hunched, vulture-like figures whose rasping voices alone could unsettle audiences. Their grip on the Crystal of Truth, however, came from a power rooted less in grandeur than in desperation. Every ruthless act was triggered by their fear of mortality and a drive to survive at any cost.

Universal Pictures, The Dark Crystal (1982)

Universal Pictures, The Dark Crystal (1982)

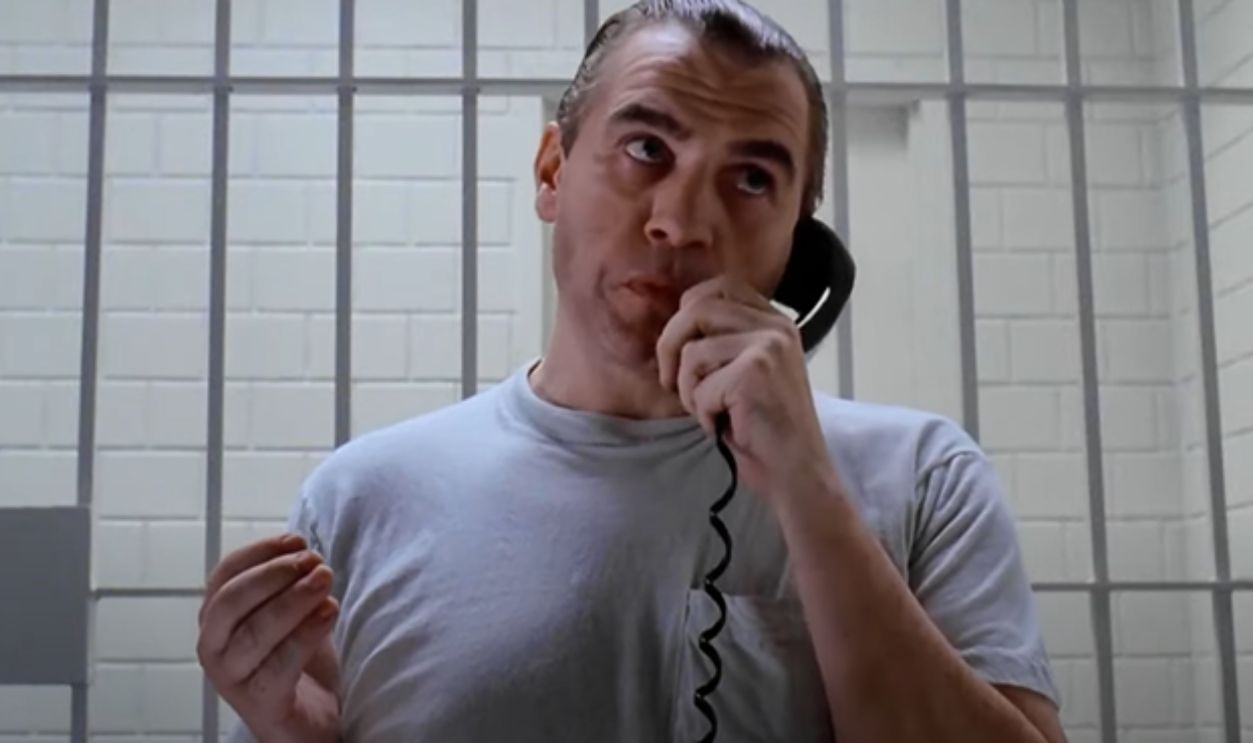

Clarence Boddicker In RoboCop (1987)

To the public, Boddicker was a sadistic gang leader. But behind the scenes, he operated under the protection of Omni Consumer Products (OCP), which used him to destabilize Detroit and justify OCP’s authoritarian policing. Boddicker’s violence simply exposed how business ambition and organized crime were entwined in the city’s downfall.

Orion Pictures, RoboCop (1987)

Orion Pictures, RoboCop (1987)

Captain Harris In Police Academy (1984)

In Police Academy, much of the comedy was slapstick—pratfalls, clumsy stunts, and the kind of banana-peel gags that never get old—framing Captain Harris as the constant target. Beneath the mockery, Harris still reminded that policing required discipline, even if the film’s bigger joke was always the mayhem of the uniformed misfits around him.

Warner Bros., Police Academy (1984)

Warner Bros., Police Academy (1984)

Xenomorph Queen In Aliens (1986)

Only when her eggs burned did the Queen reveal her rage. She ruled her hive as any mother would—protecting her children. Branded as monstrous, her actions instead reflected the primal instinct of defending the next generation, a behavior shared across nature’s fiercest guardians.

20th Century Fox, Aliens (1986)

20th Century Fox, Aliens (1986)

Mr Hand In Fast Times At Ridgemont High (1982)

Students saw Mr Hand as a joyless tyrant, raining pop quizzes and confiscations. The misunderstanding was clear; he wasn’t crushing fun, he was enforcing discipline. Hand wanted teenagers to value education over haze-filled afternoons. Authority looked harsh only because rebellion loved the spotlight.

Universal Pictures, Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)

Universal Pictures, Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)

The Terminator In The Terminator (1984)

The Terminator marched through Los Angeles with mechanical calm. Built as a cyborg assassin, he targeted Sarah Connor to stop her unborn son from leading future rebels. His mission reflected cold military logic: sacrifice one life to spare humanity from endless war.

Orion Pictures, The Terminator (1984)

Orion Pictures, The Terminator (1984)

Dark Helmet In Spaceballs (1987)

His rivalry with Lone Starr felt more childish than cosmic, in spite of his menacing appearance. In Spaceballs, Dark Helmet looked like a galactic threat but constantly tripped over his own schemes. Bound to President Skroob’s orders, he rarely acted independently and even questioned stealing planetary air.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Spaceballs (1987)

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Spaceballs (1987)

Dr Frederick Chilton In Manhunter (1986)

In Manhunter, Chilton barely speaks, a sharp contrast to later films where he preens and brags. Here, he exists as an administrator tied to Hannibal Lecter’s containment. Though silent, his role symbolizes the institutional discipline that kept genius-turned-killer separated from the outside world.

De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, Manhunter (1986)

De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, Manhunter (1986)

The Fratellis In The Goonies (1985)

Inside The Goonies, the Fratellis looked like villains chasing children, but the truth ran differently. They were holed up in an abandoned restaurant guarding stolen loot. The kids’ intrusion provoked their response, which made the family’s crime world already established rather than a plot born of playground cruelty.

Warner Bros. Pictures, from The Goonies (1985)

Warner Bros. Pictures, from The Goonies (1985)

Burke In Aliens (1986)

Every smile from Burke hid a transaction. As Weyland-Yutani’s company man, he maneuvered to secure a Xenomorph, the terrifying alien predator, for bioweapons research. Violence never touched his hands because strategy and ambition framed his decisions.

20th Century Fox, Aliens (1986)

20th Century Fox, Aliens (1986)

ET Government Agents In ET The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

The agents in ET arrived like specters from another world, sealed in hazmat gear. Their mission was simple: secure and study the unknown. What triggered them wasn’t hostility but Elliot’s secret contact, which transformed a simple procedure into a sequence audiences read as a menace on screen.

Universal Pictures, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Universal Pictures, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

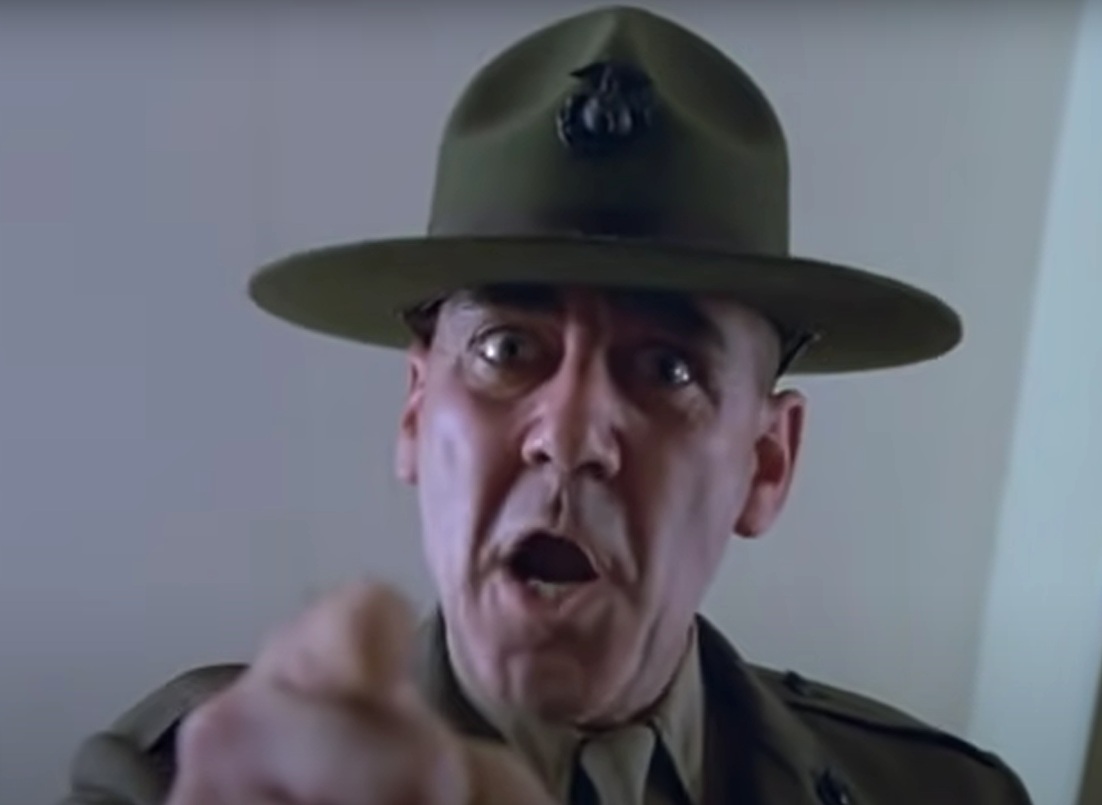

Sergeant Hartman In Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Hartman’s role in Full Metal Jacket echoed the Marine Corps’ beliefs. Boot camp required stripping recruits of weakness through verbal assault and physical strain. His voice, sharp as gunfire, carried the mission of Vietnam: mold men who could endure fear, fatigue, and relentless combat.

Warner Bros., Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Warner Bros., Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Ed Dillinge In Tron (1982)

At ENCOM, Dillinger stole Kevin Flynn’s video game designs and used the Master Control Program to protect his position. The move was ruthless and self-serving. Still, the emphasis on digital control reflected real corporate instincts, where efficiency and security often tower above fairness or creativity.

Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Tron (1982)

Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Tron (1982)

Judge Doom In Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

A black coat and sinister glare convinced audiences they faced cartoon-hating evil. The misunderstanding hid a modern dream: Doom wanted freeways, sprawling roads he believed symbolized progress. Trolley lines and Toons blocked that vision, so he cleared them with ruthless resolve, serving development over nostalgia.

Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Evil In Time Bandits (1981)

A villain called Evil looked cartoonish at first glance, although his ambitions carried logic. He mocked sloppy divine design and promoted progress through technology and reason. Beneath the jokes hid a sharp critique of blind faith, revealed most clearly in Time Bandits.

20th Century Fox, Time Bandits (1981)

20th Century Fox, Time Bandits (1981)