Number Nine, Number Nine, Number Nine...

Love it, hate it, fear it—everyone remembers the first time they stumbled into Revolution 9. It wasn’t catchy, it wasn’t comforting, and it definitely wasn’t “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” But behind those loops, whispers, and sonic chaos lies one of the strangest gambles The Beatles ever took. Did the gamble pay off? Well… what do you think?

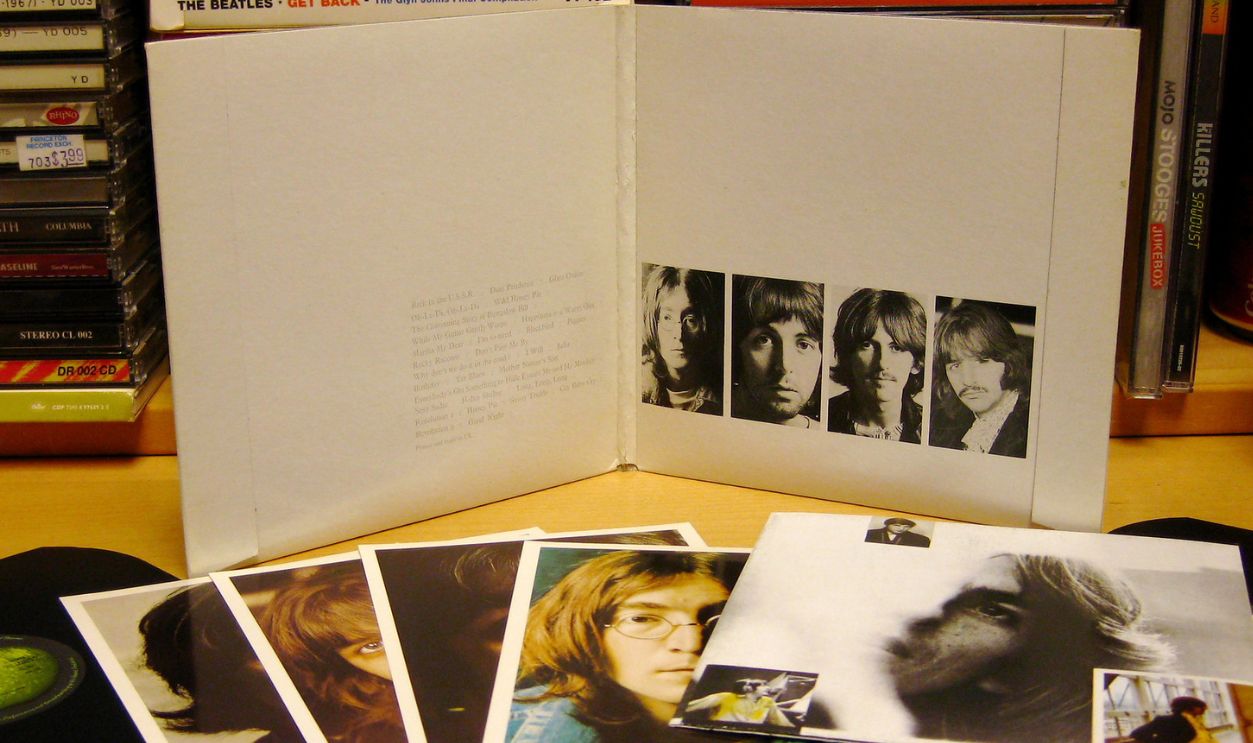

It Almost Didn’t Make the Album

We know what producer George Martin thought. He was uneasy about including Revolution 9 on the White Album and reportedly argued it didn’t belong. Several accounts say McCartney also pushed to leave it off. But Lennon supported it—and in 1968’s fractured band dynamic, the strongest-willed Beatle often got his way.

The Song That Barely Feels Like a Song

There’s no chorus, no verses, no melody—just an evolving collage of noises. Revolution 9 behaves more like a sound installation than a Beatles track. It was assembled from fragments rather than written, making it the most unconventional piece in their entire discography.

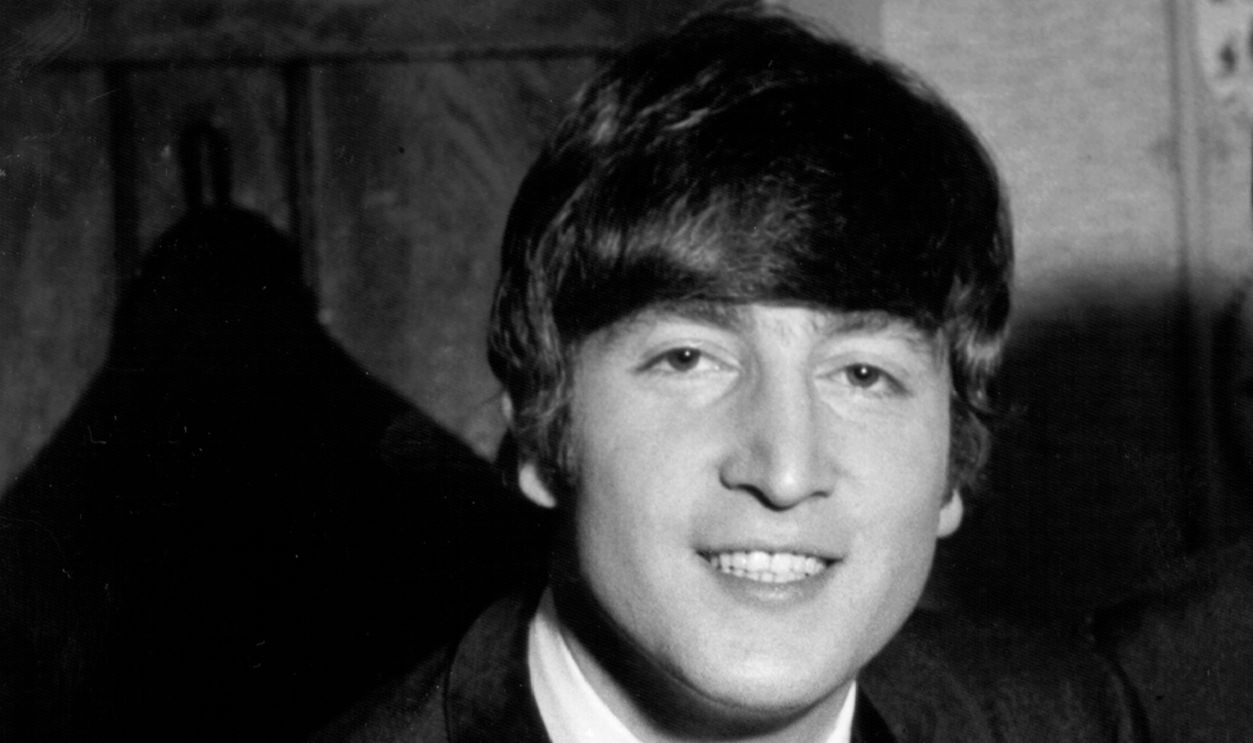

John Lennon Wanted a “Sound Picture”

Lennon envisioned Revolution 9 as an audio snapshot of chaos, building off ideas he’d explored during the creation of “Revolution 1.” He described it as a kind of sound painting—more conceptual than musical—and intentionally destabilizing for the listener.

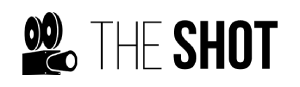

Tony Barnard, Los Angeles Times, Wikimedia Commons

Tony Barnard, Los Angeles Times, Wikimedia Commons

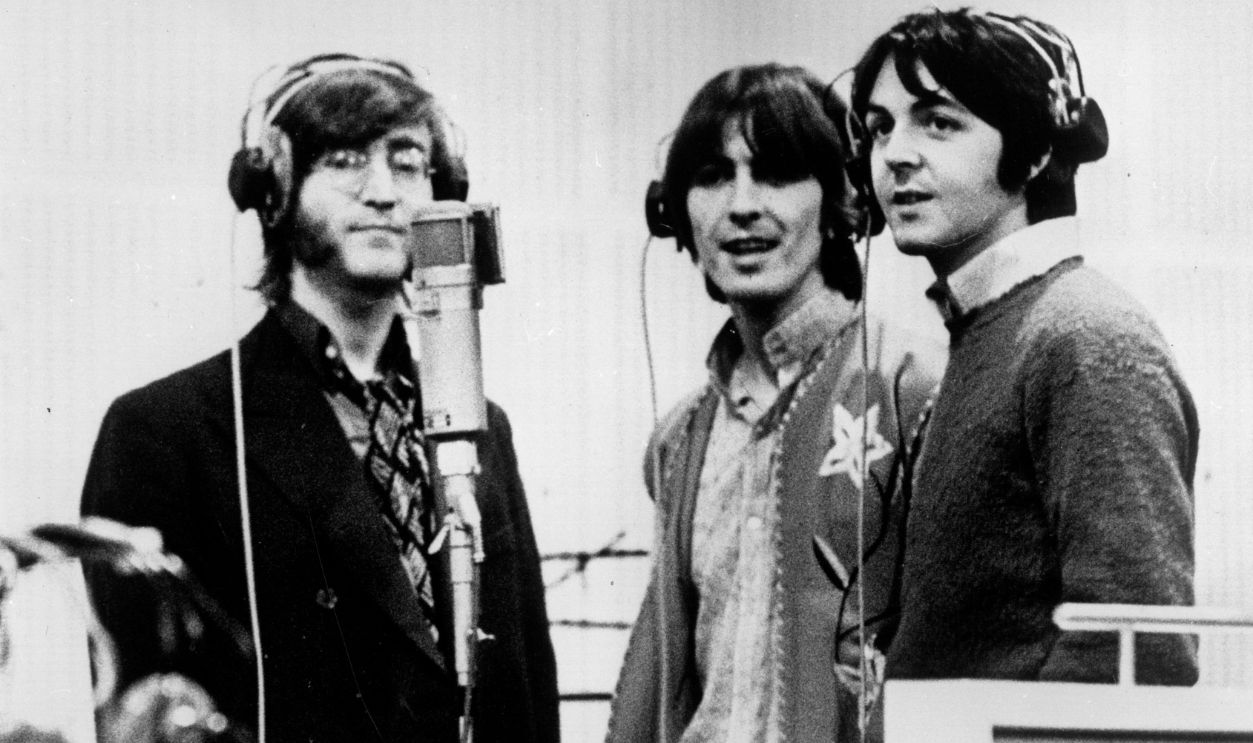

The Tape Loop Madness Behind It

The track draws from dozens of tape loops filled with classical snippets, radio interference, spoken phrases, reversed recordings, and stray studio noise. Lennon, Harrison, and Yoko Ono manipulated them live during mixing sessions, pulling pieces in and out like early turntable experimenters decades before sampling became mainstream.

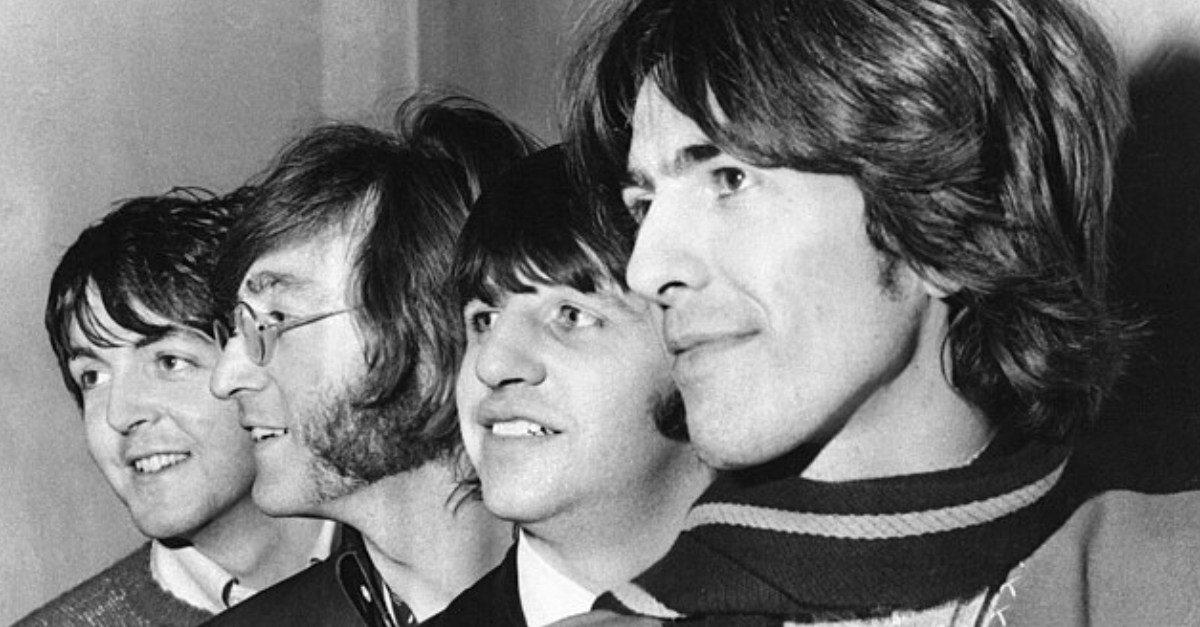

Joost Evers / Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

Joost Evers / Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

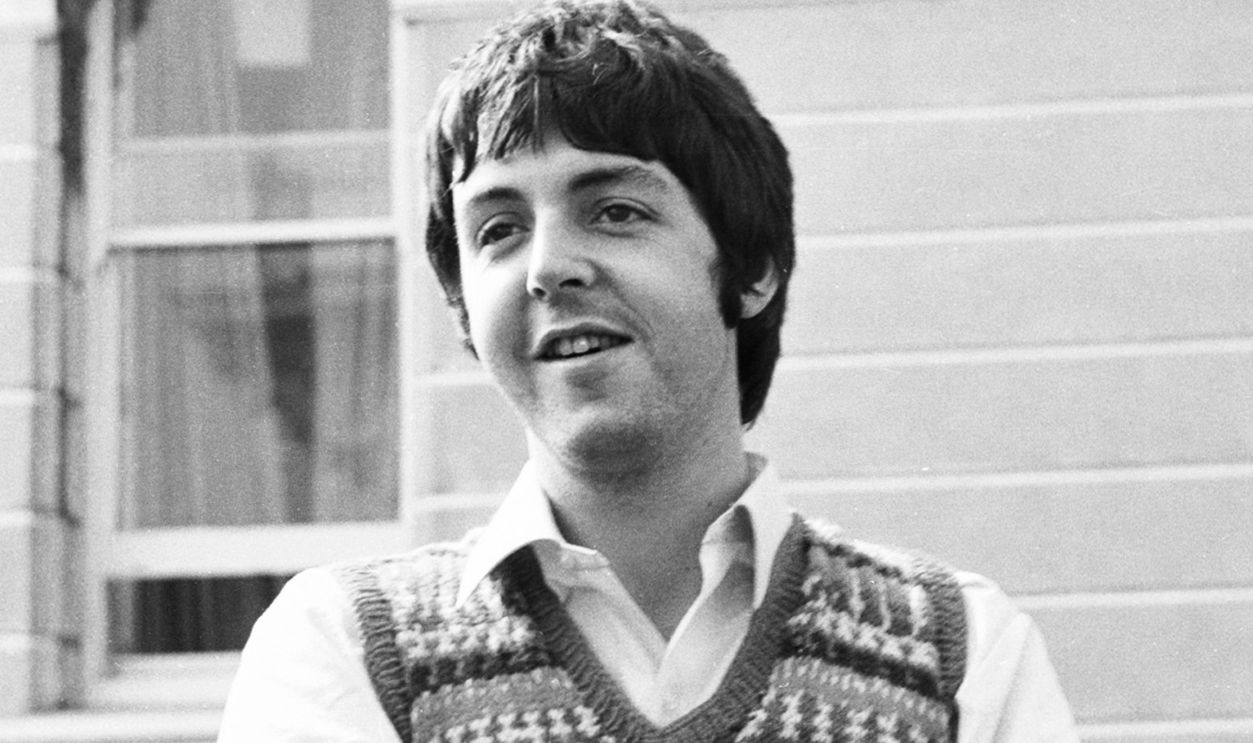

Paul Actually Helped Start It (Sort Of)

The roots of Revolution 9 stretch back to McCartney’s earlier tape-loop experiments during the creation of “Tomorrow Never Knows.” He later noted that he was heavily into avant-garde techniques at the time—even if he wasn’t fully on board with this track ending up on a Beatles album.

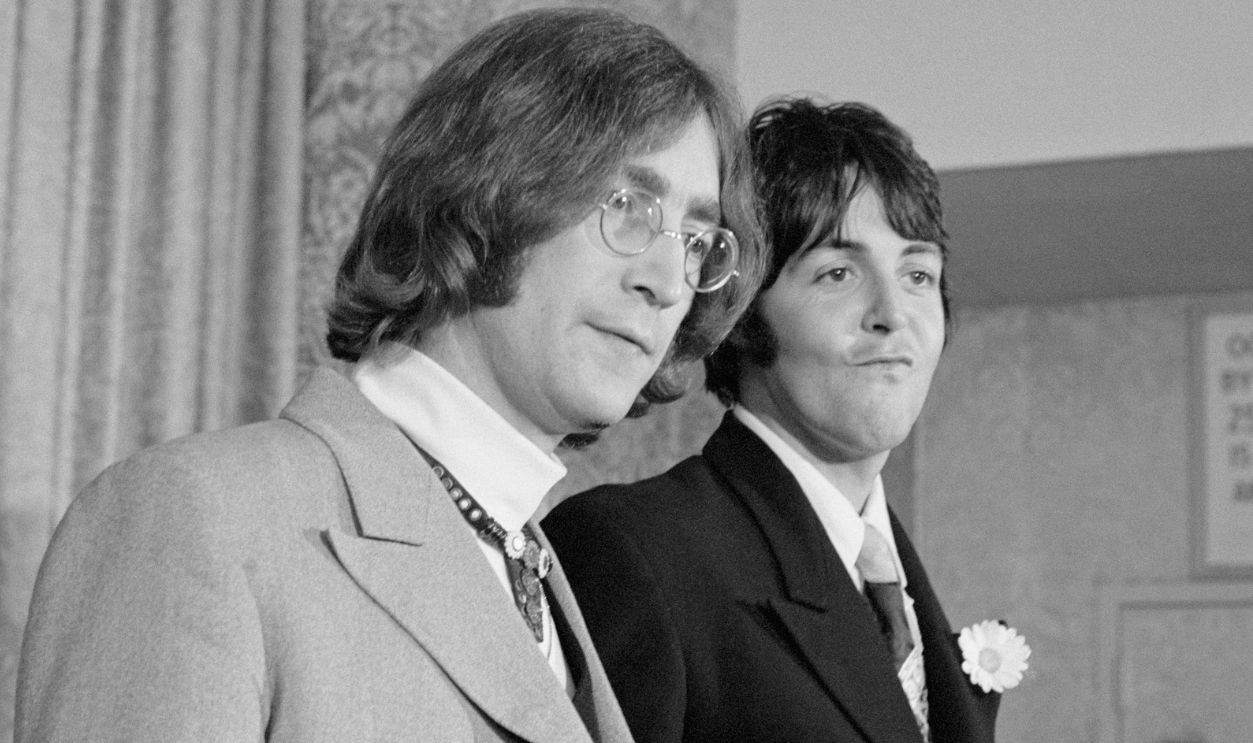

Keystone Features, Getty Images

Keystone Features, Getty Images

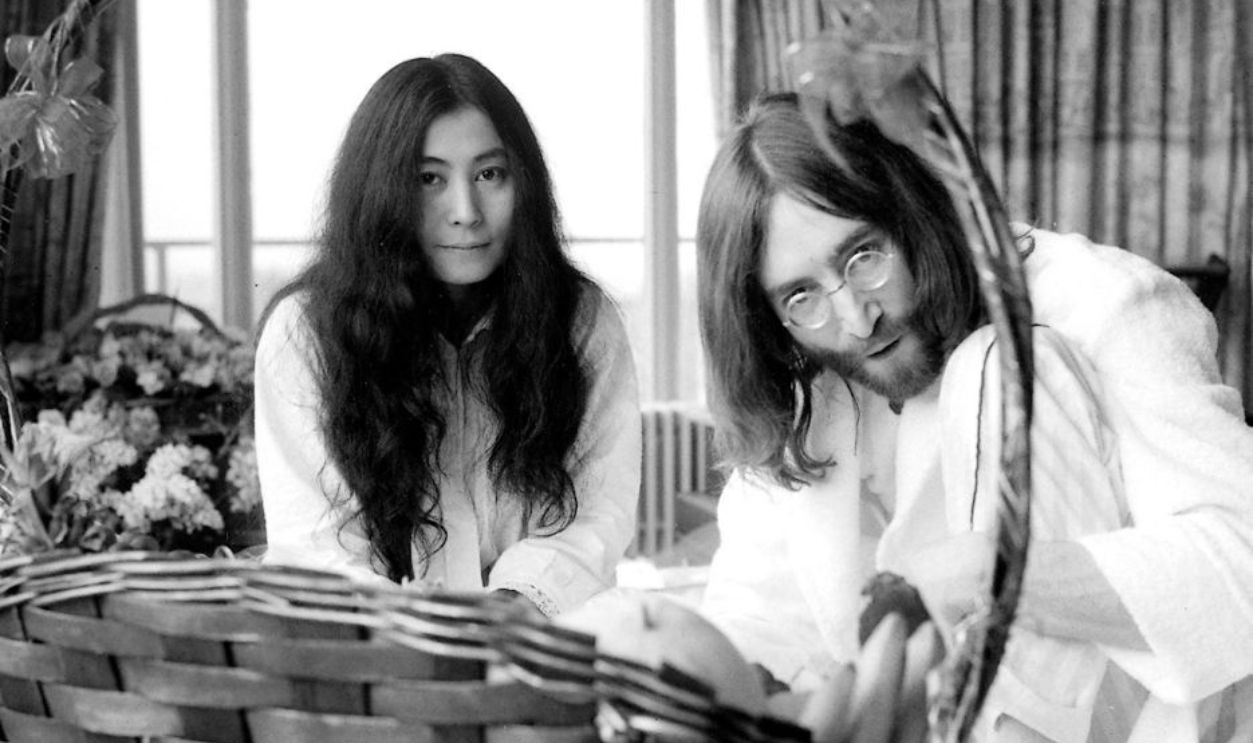

Yoko Ono’s Influence Was Massive

Ono’s background in experimental art and Fluxus concepts shaped Lennon’s approach. Her ideas about repetition, abstraction, and sound-as-art flowed directly into Revolution 9. Even critics who dislike the track acknowledge her influence.

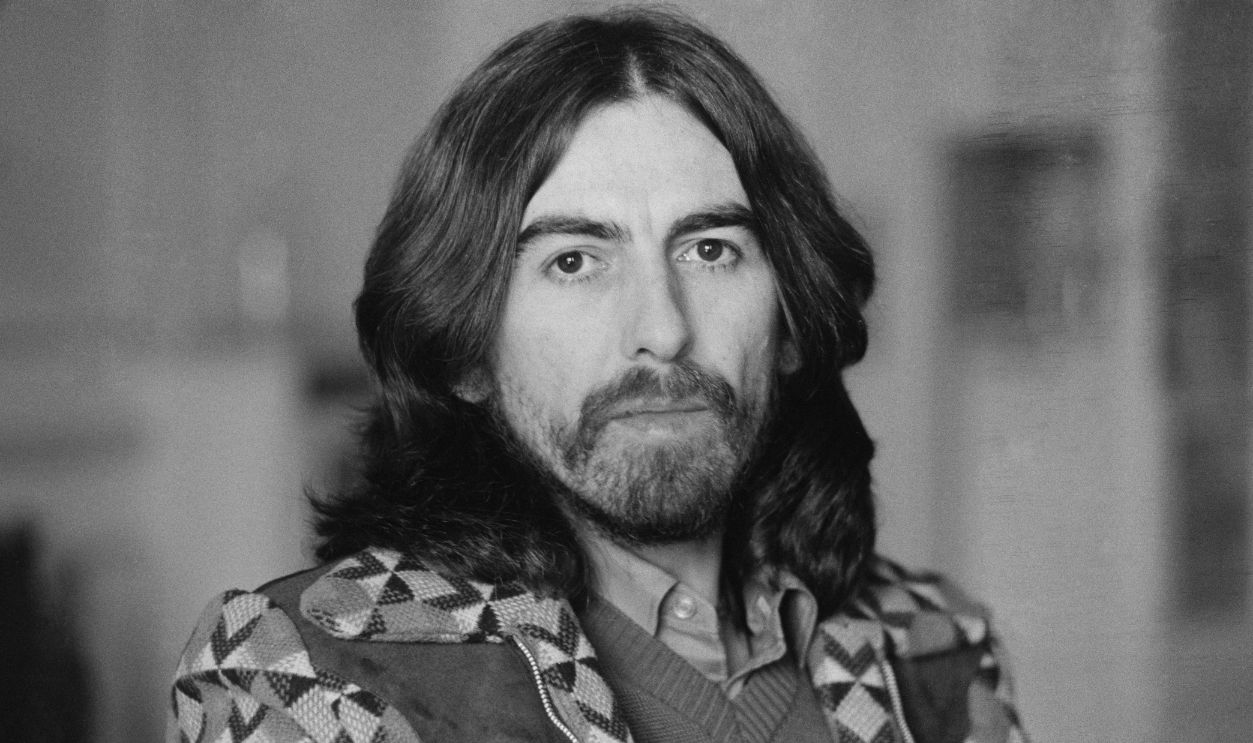

George Harrison Was Weirdly Into It

Harrison, already exploring Indian classical and early electronic music, embraced the free-form chaos. He assisted with loops and sounds during the sessions and appreciated the piece as a chance to break away from traditional pop structures.

Ringo? He Mostly Stayed Out of It

Ringo Starr had minimal involvement in the track’s creation. While he didn’t object to its inclusion, he wasn’t heavily involved in shaping it. Revolution 9 remained primarily a Lennon–Ono–Harrison experiment.

Shepard Sherbell, Getty Images

Shepard Sherbell, Getty Images

The Most Repeated Phrase Ever: “Number Nine…”

The eerie “number nine” loop came from an EMI test tape used for checking playback equipment. Lennon was fascinated by the phrase and looped it repeatedly until it became the central motif. Ironically, it was never intended for a musical project.

Fans Thought It Was a Hidden Message

During the peak of the “Paul Is Dead” conspiracy, some listeners claimed that playing Revolution 9 backward revealed “turn me on, dead man.” Whether intentional or not, the alleged backmasking became one of the track’s most notorious talking points.

Music Critics Absolutely Hated It at First

Early reviews were not kind. Many critics called the piece confusing, self-indulgent, or simply unpleasant. Even loyal Beatles fans were stunned that something so abrasive appeared on such an anticipated album.

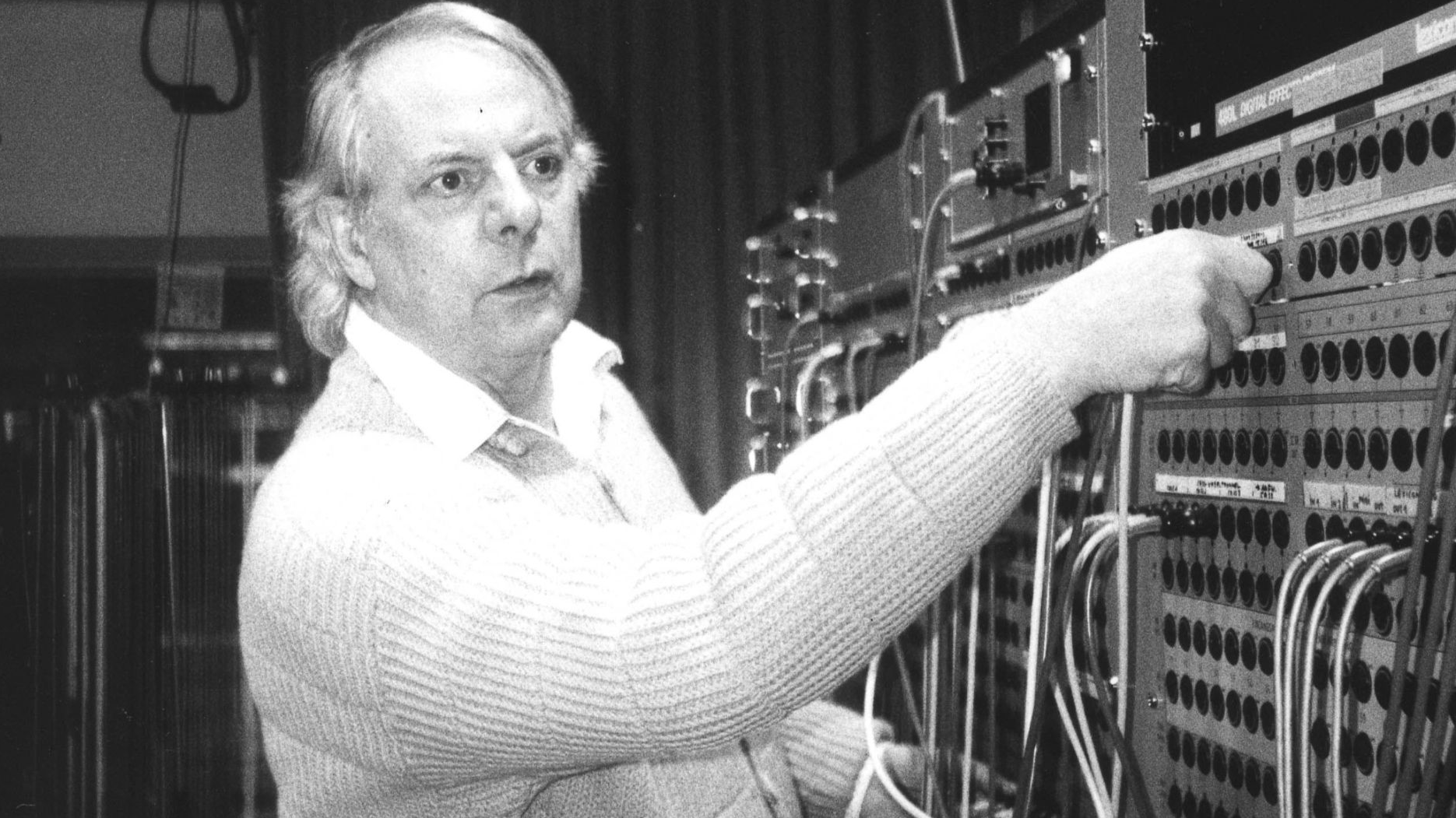

Bernard Gotfryd, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gotfryd, Wikimedia Commons

But Avant-Garde Fans Loved It

Within experimental and art-music circles, Revolution 9 found real appreciation. Some critics and composers compared it to works by Stockhausen and Cage, recognizing The Beatles’ willingness to step boldly into avant-garde territory.

Kathinka Pasveer, Wikimedia Commons

Kathinka Pasveer, Wikimedia Commons

Lennon Thought Listeners Would “Catch Up”

Lennon defended the track enthusiastically. He believed audiences would eventually understand it better and often framed it as a serious artistic experiment rather than a joke or an indulgence.

Bob Gruen; Distributed by Capitol Records, Wikimedia Commons

Bob Gruen; Distributed by Capitol Records, Wikimedia Commons

McCartney Later Downplayed His Role

McCartney contributed early tape-loop ideas and had pioneered similar studio experiments earlier in the decade, but he later distanced himself from the finished track. He suggested that this kind of piece fit better in an art setting than on a Beatles record.

It Reflected a Growing Divide in the Band

The sessions for Revolution 9 highlighted the band’s fragmented working style. Lennon and Ono worked obsessively on the piece, while the others focused on their own songs separately—a dynamic common during the tense White Album period.

Bernard Gotfryd, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gotfryd, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Manson Misinterpreted It Horrifically

Manson believed the track contained coded apocalyptic messages—a claim that horrified the band. Lennon later dismissed the association outright, though the link became a grim footnote in the song’s history.

It Inspired Future Experimenters

Revolution 9 is frequently cited by fans of noise, electronic, and collage-based music as an early example of mainstream artists pushing experimental boundaries. While its direct influence is debated, it certainly anticipated techniques later embraced widely.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Modern Critics Have Softened Toward It

Today, critics are far more open to the track’s ambition. Outlets like Rolling Stone describe it as bold, radical, and ahead of its time—even if they still admit it’s not something most listeners want on repeat.

It’s Still the Track Most People Skip

Even devoted Beatles fans admit that eight minutes of disorienting collage isn’t casual listening. Revolution 9 may be respected, but it’s rarely anyone’s go-to track from the album.

But It’s Also Gained a Cult Following

Some listeners adore the piece. Online communities analyze its structure, sources, and sequencing in meticulous detail. To these fans, the track is a window into Lennon’s most unfiltered artistic impulses.

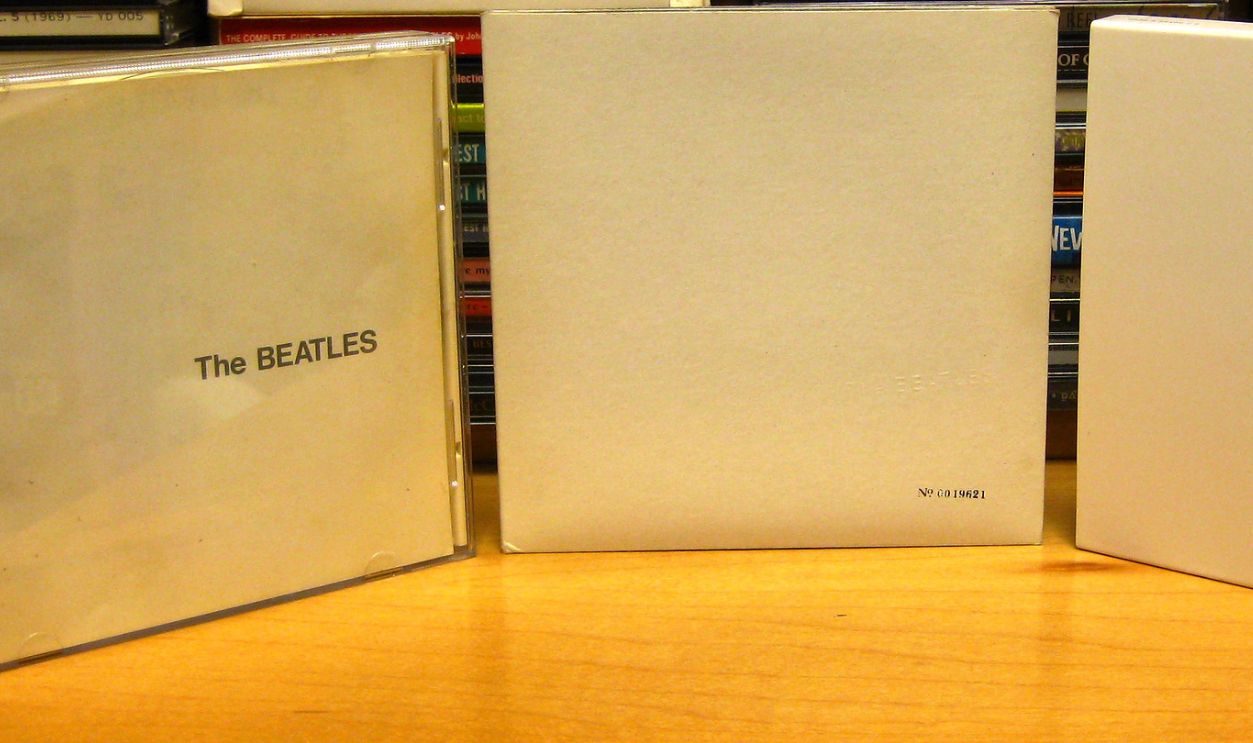

Without It, The White Album Wouldn’t Be The White Album

The White Album is beloved for its chaos, variety, and sharp stylistic turns. Revolution 9 is its strangest detour—and without it, the album would feel safer, tidier, and far less intriguing.

So… Masterpiece or Disaster?

Maybe it’s both. It’s confusing, daring, frustrating, hypnotic, and completely unforgettable. No other Beatles track inspires arguments like this one—which might be the clearest sign that Revolution 9 did exactly what Lennon intended.

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives, Getty Images

You Might Also Like:

Facts About The Beatles Most Beatlemaniacs Probably Don't Even Know

Beatles Quiz: Can You Match These Lyrics To The Right Beatles Song?