The Rumpled Sleuth Who Ruled Primetime

Peter Falk didn’t just play Lt. Columbo, he engineered a phenomenon: a gentle, relentless detective who could disarm millionaires with a shrug and a smile. Beginning with a 1968 TV movie and the series run that followed, Falk’s Columbo rewired how TV mysteries could feel: cozy on the surface, razor-sharp underneath.

“One Eye? No Problem.”

At age three, Falk lost his right eye to retinoblastoma and wore a prosthetic for the rest of his life, which helped craft Columbo’s unmistakable squint. He never let it limit him, on fields, on stages, or on sets.

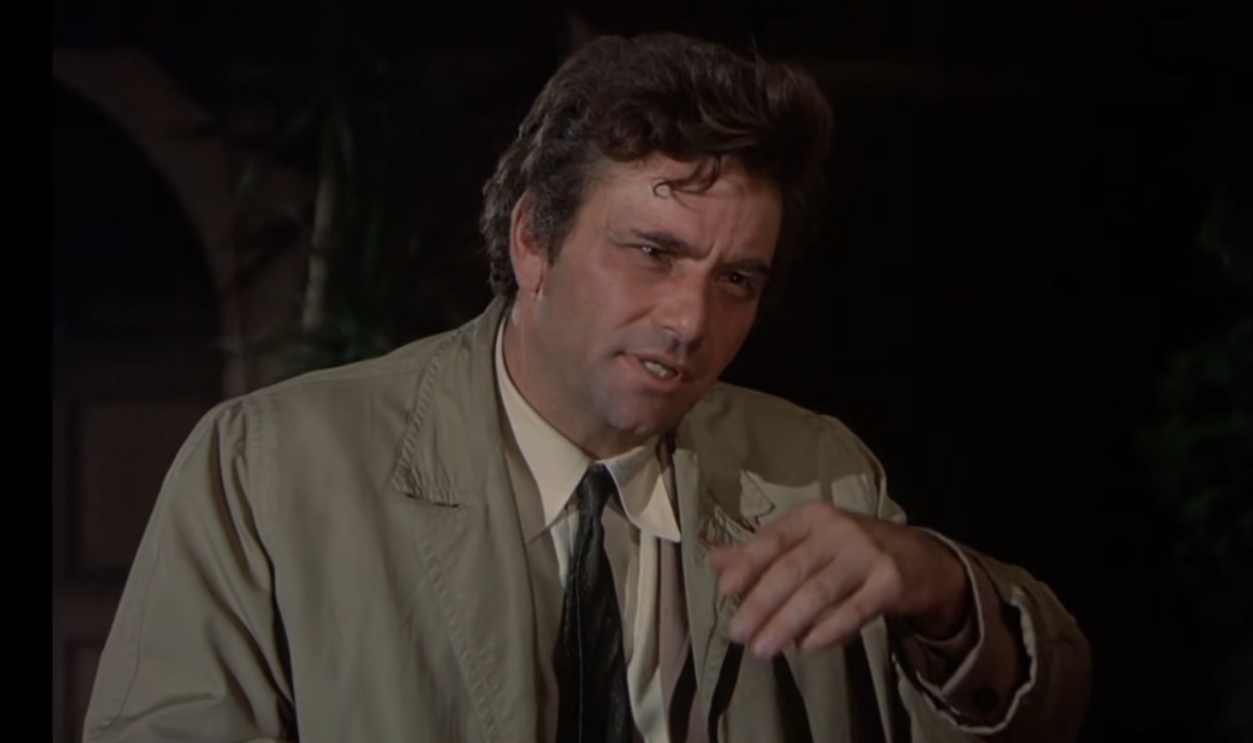

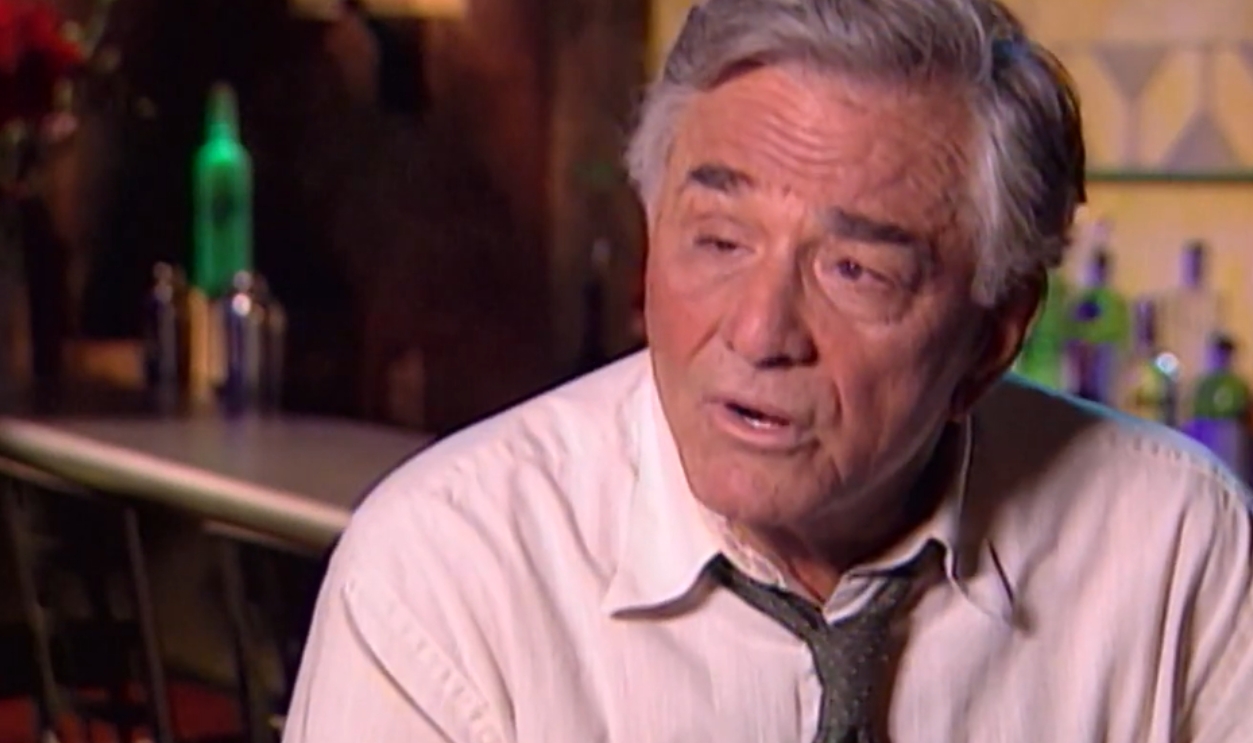

Interview With Peter Falk | 50 Years of Columbo (Columbo Featurette), Columbo

Interview With Peter Falk | 50 Years of Columbo (Columbo Featurette), Columbo

Budget Analyst by Day, Actor by Destiny

Before show business, Falk earned a B.A. at the New School and an M.P.A. at Syracuse, then worked as a management analyst in Connecticut. He even once tried (and failed) to join the CIA, a detour he recounts with characteristic wry humor in his memoir.

The Breakthrough: A Hitman and Two Oscar Nods

Falk’s film turn as the twisted Abe Reles in Murder, Inc. (1960) announced a major talent; Pocketful of Miracles (1961) brought a second straight Oscar nomination for Supporting Actor. The tough-guy chops were real, but the twinkle was too.

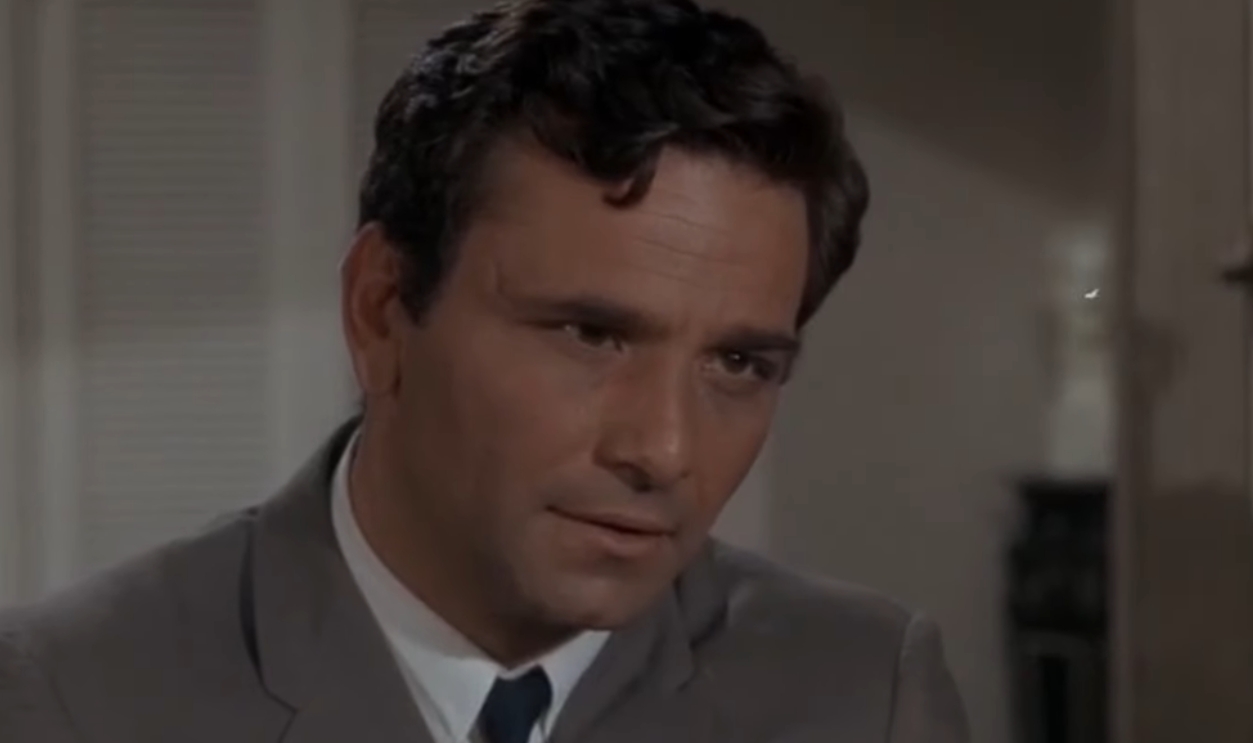

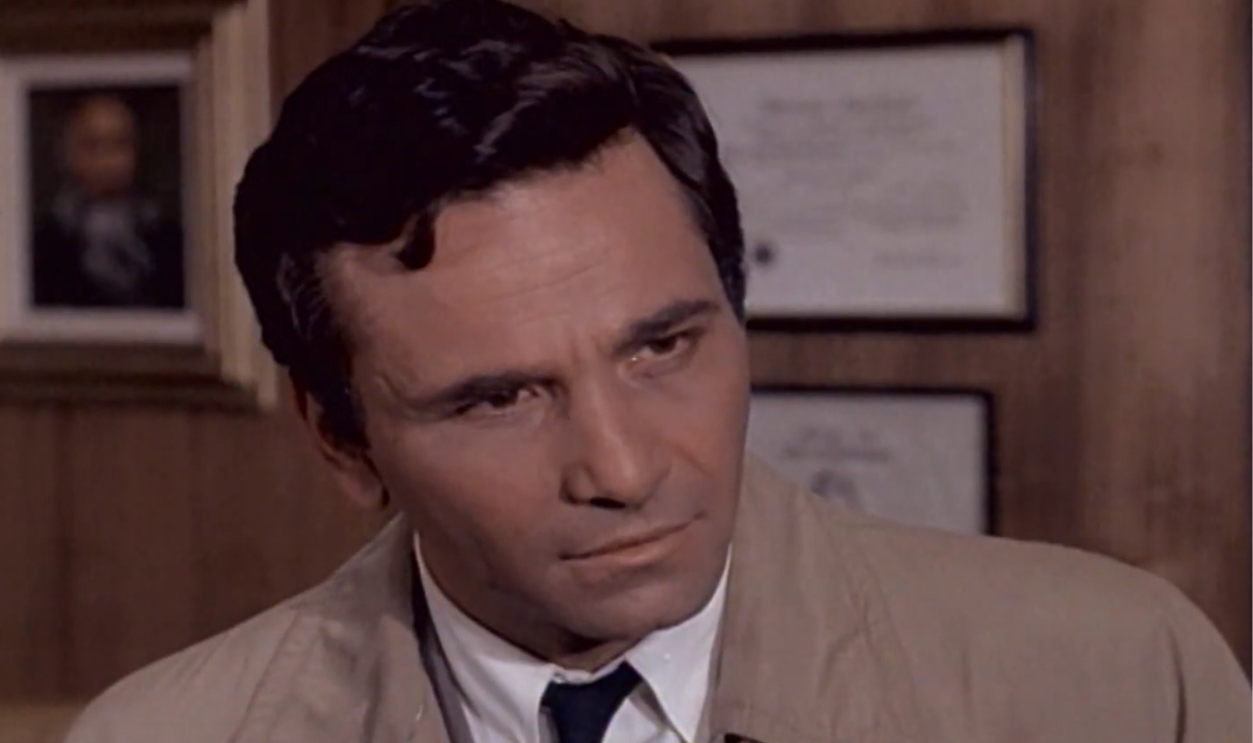

United Artists, Pocketful of Miracles (1961)

United Artists, Pocketful of Miracles (1961)

“Prescription: Murder” to Prime-Time Royalty

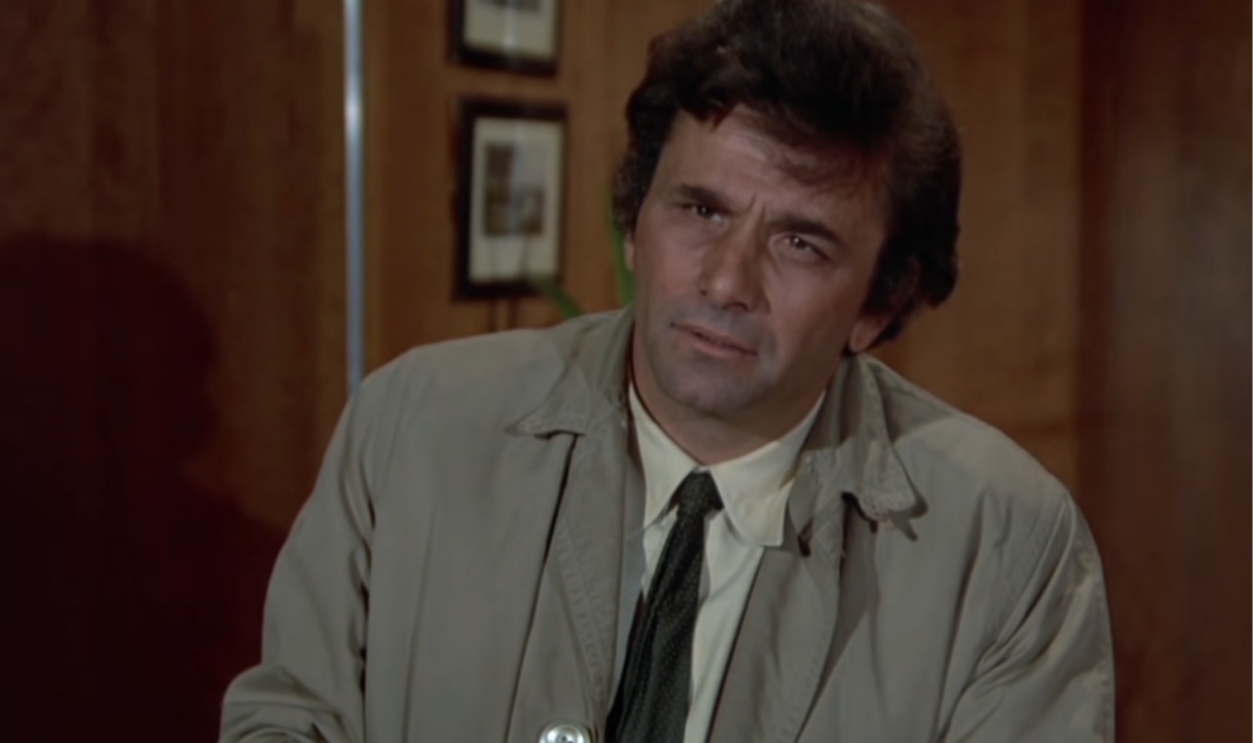

Columbo began as a TV movie (Prescription: Murder, 1968), then became a series built on the “inverted mystery,” revealing the killer first and savoring the cat-and-mouse. Falk’s Lieutenant Frank Columbo was the antidote to swagger: baggy, polite, and unstoppable.

The $15 Raincoat and a Cigar, Costuming a Legend

Falk helped invent Columbo’s look himself, famously supplying the shabby raincoat and the stubby cigar, props that doubled as character psychology. The coat’s origin story has been retold in different ways by seemingly everyone involved in the show; but either way, the rumpled coat became TV iconography.

“Just One More Thing”: A Catchphrase with Teeth

Falk’s detective feigned distraction, then pounced with a final, devastating question. In his memoir, he describes building mannerisms “outside-in," a craftsman’s approach that made the catchphrase feel like a trap sprung with a smile.

The Columbo Schedule: Slow, Luxurious, and Global

Unlike weekly whodunits, Columbo aired as feature-length TV films, first from 1971–78, then in revived runs from 1989–2003. Unlike most detective shows on the air, the format let Falk and guest stars breathe; and it paid off. Audiences around the world kept showing up for the Lieutenant’s amiable ambush, even though they knew it was coming every time.

Five Emmys, Countless “Gotchas”

Falk won four Emmys for Columbo (1972, 1975, 1976, 1990) and another for 1962’s “The Price of Tomatoes,” cementing his peer-respected legacy. That mix of awards from his Hollywood peers and crossover pop devotion is rare—and exactly what he earned.

Peter Falk Wins Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series | Emmy Archive 1990, Television Academy

Peter Falk Wins Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series | Emmy Archive 1990, Television Academy

Cassavetes’ Co-Conspirator: The Art-House Falk

Beyond TV, Falk was a vital player in American indie film, especially with John Cassavetes: Husbands (1969), A Woman Under the Influence (1974), and Elaine May: Mikey and Nicky (1976). On film, Falk could be volcanic or tender. Often, he was both in a single scene.

Paramount Pictures, Mikey and Nicky (1976)

Paramount Pictures, Mikey and Nicky (1976)

A Guardian Angel (Sort Of) in Wings of Desire

In Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987), Falk plays the role he was born to play: Peter Falk, a fallen angel turned actor, wandering Berlin with uncanny empathy. The meta-cameo distilled the persona he carried: earthy, amused, curious, and kind.

Road Movies Filmproduktion, Wings of Desire (1987)

Road Movies Filmproduktion, Wings of Desire (1987)

The Grandpa Who Narrates Our Childhoods

Another generation knows Falk as the warm, wise storyteller in The Princess Bride (1987), bookending the fantasy with a voice you’d trust with anything. He’s the movie’s heartbeat, gently talking us into happily-ever-after.

20th Century Fox, The Princess Bride (1987)

20th Century Fox, The Princess Bride (1987)

An Artist with a Pencil and a Punchline

Falk also sketched and painted, and many interviewers over the years noted how drawing relaxed him between roles. The same observational patience that trapped murderers on TV helped him capture faces on paper. (“Just hold still...one more line…”)

How He Worked: Curious First, Clever Always

Falk’s process prioritized behavior: posture, props, pauses. Reviews of his memoir emphasize how consciously and specifically he built Columbo from the outside—coat, car, cigar. From there, he simply let intuition find the man's soul. It may seem audaciously simple, but Falk's methods masked some serious craft.

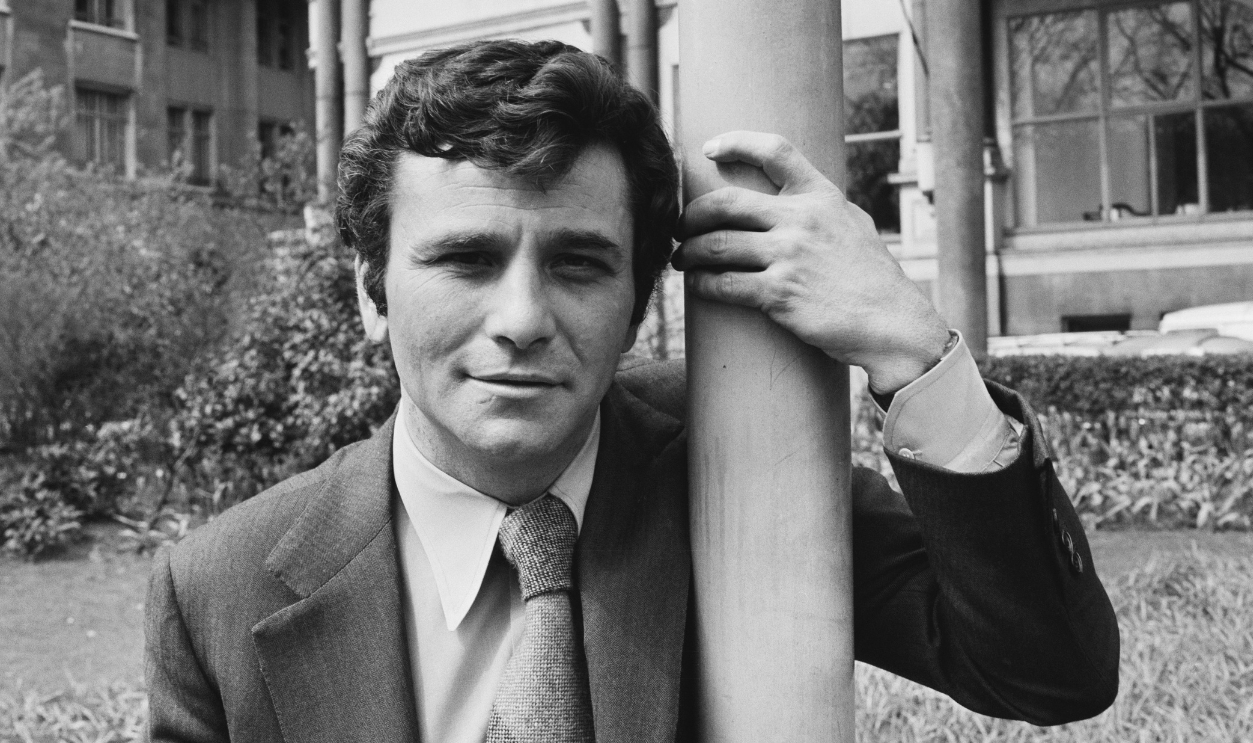

John Turner, Wikimedia Commons

John Turner, Wikimedia Commons

The Final Runs: Still Stealing Scenes in the 2000s

Even after the last regular Columbo films (2003), Falk kept acting: the family dramedy The Thing About My Folks (2005) and a wry supporting turn in Next (2007), proved his timing was intact and the charm undimmed.

Picturehouse, The Thing About My Folks (2005)

Picturehouse, The Thing About My Folks (2005)

2007–2009: Health Clouds Gather

Public reports in late 2008 revealed Falk had Alzheimer’s disease; a 2009 Los Angeles conservatorship hearing described a rapid decline after dental procedures in 2007. His family and the court worked to ensure his care.

A Peaceful Goodbye, and a Sea of Tributes

Falk died at home in Beverly Hills on June 23, 2011, at 83. Tributes from colleagues and the press emphasized what fans already knew: the man behind the raincoat was a master actor and a mensch.

The Rewatch Boom: Columbo Keeps Converting New Fans

Reruns and streaming have minted new Columbo obsessives; writers still cite the character’s influence on modern mystery storytelling and “cozy” crime. The rumpled lieutenant remains evergreen.

What Columbo Teaches: Empathy as Superpower

Falk’s genius was making intellect feel humane. Columbo wins by listening, noticing, and caring, then closing the jaws with a single polite question. It’s detective work as a moral art, performed by an actor who believed in people.

“Just One More Thing”… About Legacy

Peter Falk made Columbo a sensation not with fireworks but with warmth, wit, and craft so precise you barely noticed it. He worked right into the mid-2000s; when dementia arrived, it couldn’t erase the decades he’d already given us—or the grin we still feel when the raincoat enters the room.